Published in 1944, Alfred Perlès’s Alien Corn gives a fascinating account of joining and serving in the Pioneer Corps. It also provides an outsider’s view of Kitchener camp and its refugees. While it is one man’s view and of course subjective, and the views expressed are sometimes highly problematic in their depiction of those from different countries and religions, it is nevertheless interesting to have a contemporary perspective.

I would recommend that anyone interested in this part of the Kitchener history tries to get hold of a copy, although it isn’t easy to do so because it is out of print.

Some extracts relevant to our Kitchener context are reproduced below.

……………….

“The signing up was easy enough. I did not think it would be, but I was wrong. Very few questions were asked, red tape being reduced to the minimum. It took the recruiting sergeant less than ten minutes to get my signature on the dotted line, and, after all, why should it have been otherwise? …

At the “medical” they were a bit fussier. To begin with, they made us undress in a vast, overheated room, empty except for some forms along the walls. There we sat, some eighty or ninety men, naked, hot, yet shivering with nudity and self-consciousness, waiting to be ushered into the next room, where the Medical Board were working overtime getting new recruits into the ranks of H.M.’s Forces.

By my side sat an elderly bloke, forty-five or fifty years of age, who kept scratching his back with great nonchalance. He looked as though he had not been naked like that for a long time. … He had been in the last war, and lost no time telling me all about his four years in the trenches. He seemed quite happy at the prospect of getting back into the army, as though one world war were not enough for one short life.

From the waiting-room we passed, one by one, into the Medical Board Room. Each time the turn of the man nearest the door came, the next man would get into the latter’s place, the rest if us moving one seat up. Needless to say, the seats were kept warm.

Frankly, I did not like it at all; I felt nervous, ill at ease, and slightly disheartened. I had forgotten where I had left my clothes, else I might have attempted a last-minute get-away, even though I had already signed on the dotted line. …

When at last, after a couple of hours or so, my turn came, I walked into the adjacent room with as much ease and assurance as I could muster, but I very much doubt that I cut a good figure. There is something galling and humiliating about being compelled to appear naked in front of others who are dressed; I could not help feeling at a disadvantage.

I forget exactly how many M.O.s there were in that room, but I have the vivid recollection that they were numerous; one, perhaps, for every vital organ. Some wore civilian clothes, others were in army uniforms, and they examined me thoroughly, painstakingly, conscientiously. I smiled at the idea flitting through my mind that, had I called on all those specialists, individually, in their Harley Street consulting rooms, the fees would have added up to a handsome total. As it was, I got everything free of charge. It was a real service! …

They kept making notes, and comparing them, and adding them up; and when there were no more specialists, and I was through with the rigmarole, the head doctor gave me an encouraging look and a foolscap sheet: my medical-history sheet. In the left-hand corner, in red ink, I read, “A 1”.

……………….

C.O.E.s, R.C.s, and J.s were sworn in simultaneously. All we had to do was to place our left hand on the Bible and, right hand raised, repeat the words of the officer. Strictly speaking, the R.C.s ought to have been sworn in by the crucifix, but there was no crucifix, and nobody raised any objections. The Lieutenant-Colonel gave us the oath of allegiance in small doses, a few words at a time, like a stage prompter, and we repeated them, like ham actors. I forget the exact wording of the oath by which we swore allegiance to H.M. King George VI, but I remember it sounded rather solemn, and we felt quite elated, especially when the officer presented each of us with the King’s Shilling. The King’s Shilling, together with the first day’s ration money, amounted to three shillings and sixpence. … That was that. It was late in the afternoon when we were through, and we were to report on the following morning, at nine, at the recruiting station, to be taken to our respective depots. We had one more night to spend in Civvie Street, and we were determined to make a success of it.

……………….

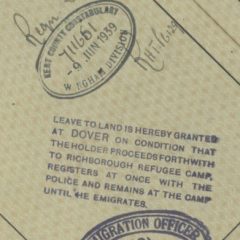

Bright and early next morning I reported back to the recruiting office. All I knew was that I had been drafted to No.3 Training Centre, A.M.P.C., Kitchener Camp, Richborough, near Sandwich, Kent. That much I was told beforehand. In the British Army an alien could be but a Pioneer, and being an alien I was to be a Pioneer.

Incidentally, I do not like that word, alien; the word has a derogatory, hostile, almost cruel ring. I should have much preferred being called a stranger. But stranger was, perhaps, too vague a term; anybody from Yorkshire, or Dorset, would be a stranger in Kent, without being an alien. Why, then, couldn’t we just be foreigners? It would have sounded less humiliating than alien.

We were all present, the whole batch of us destined for Richborough. I gave my comrades-to-be the once-over. Somehow they struck me as a rather queer lot – not at all like soldiers, nor even what I should have thought to be the raw material of soldiers. What struck me particularly was the fact that nearly all seemed extremely well dressed. It was not that they wore new suits: but their clothes bore the unmistakable cachet of expensive tailors. Soldiers, as a rule, do not turn up like that.

The suitcases, too, looked far too elegant for soldiers; some carried smart pigskin valises stuck with labels of famous hotels. At random I read: Hôtel Continental Paris -Villa d’Este – Hôtel Pupp Carlsbad – Hotel Vier Jahreszeiten Munchen – Plaza New York – Hotel Bristol Wien, and so on. … [A] somewhat “ritzy crowd”.

……………….

“We’re in for it,” I said, starting the conversation. “I wonder what Richborough’s like.”

“Should be quite all right,” he answered. “They began building Kitchener Camp during the last war. I understand it’s full of refugees now.”

“All Germans, I suppose?”

“Yes, and Austrians … mostly Jews,” he said. His English sounded perfect – too perfect, in fact, for an Englishman; no native could have such a clear and distinct enunciation unless he was a B.B.C. announcer.

“Where do you come from?” I asked.

“From Cologne,” he smiled. … he had been living in England since 1929.

……………….

From Dover to Sandwich the journey was short and uneventful. The German was fast asleep and snoring loudly. … We drank whiskey and ate the few sandwiches I had brought with me.

At Sandwich, a corporal from the centre took charge of us. It was early afternoon. I could not actually see the sea, but could smell its nearness. It was lovely, exhilarating spring, the air as clear as a bell, full of sun, and youth, and salt.

……………….

It would be a gross overstatement of facts if I said that I was thrilled by my first contact with the A.M.P.C. and the Pioneers. To tell the truth, I was at first confused and baffled, and it took me days, nay, weeks, to overcome my bewilderment and find my bearings among that queer set of people, and to fit myself, tentatively at least, to the new surroundings. And to strip Truth of her last shreds of raiment I might as well confess that even now – that is, a little over three years after my first impact with the alien Pioneers – I at times am still puzzled and vaguely incommoded by certain to me incomprehensible traits in the psycho-spiritual make-up of my comrades.

Upon arrival at Richborough, I at once became aware of a bizarre atmosphere that seemed to pervade the length and breadth of Kitchener Camp; an atmosphere made up, I felt, of a series of contradictory emotional currents: of psychological stress and psychological relief; of mental strain and mental exuberance; of physical well-being and the dread of physical suffering.

As I was soon to learn, most of the men gathered together at Kitchener Camp had only quite recently reached the friendly shores of this island, coming from Nazi-ridden Central Europe; and they had not yet been able to free their minds and souls from the miscellaneous horrors they had barely escaped. Kitchener Camp, to the great majority, was a kind of purgatory – an ante-room to either heaven or hell. It was, of course, heaven, but the refugees could not yet see it in that light; they could not believe the evidence of the mere fact of escape. Accustomed to think of their lives in terms of hell on earth, the heaven of the south-east coast of England was too bright to be true. There had been no transition from one form of existence to the other. Thus, although their troubles were over, they continued out of habit to worry and fret, their keyed-up intelligences always open to the possible contingency of some new disaster

It was about two in the afternoon when we reached camp. We were shown to our huts and offered food, but none of us newcomers had much desire to eat; we were too nervous for that, and nervousness is the enemy of appetite. So instead of proceeding to the cookhouse we took a look round the camp, trying to familiarise ourselves with the topography of the place. The next day we were to be interviewed individually, by the O.C., and issued with our uniforms and army kit. In the meantime there was nothing for us to do except take in the picture.

The camp proper, about two miles from Sandwich, was situated to the right and left of the main road between Deal and Ramsgate, and was divided into two parts; the one the military camp of the A.M.P.C., the other part being reserved for the civilian refugees. But there was apparently no strictly delineated borderline between the two camps, with the result that soldiers and civilians mixed freely. The canteen, especially, though nominally run on Army lines, was frequented by Pioneers and civilians alike. The latter, for the greater part German and Austrian Jews, with a sprinkling of Czechs and Sudeten Germans, had arrived in organised refugee transports shortly before the outbreak of war. Sent directly to Richborough they were not supposed to scatter over the British Isles; pending obtention of emigration visas to the Dominions and the U.S.A., they were lodged and fed in Kitchener Camp. It was, in fact, from amongst them that the alien Pioneer Corps, when instituted in November 1939, recruited its first volunteer members.

The dreary sight of the camp and the multitudes of unknown men gave me a sensation of utter loneliness. Never before had I felt so lonely and forlorn as on that first afternoon in the Army. There must have been some two or three thousand men in camp, and in their midst I was as isolated as a cable sunk at the bottom of the sea. They were all foreigners, “aliens” to the British, but no less alien to me who was myself an alien. I felt ill at ease, unhappy, a stranger lost in a strange land, and without hope of escape. All of them were refugees from the most horrible oppression of modern history, and hence, I strove to convince myself, worth of sympathy and compassion. My heart should have gone out to them, but it did not. I had never been able to thrive in an atmosphere of misery and mental stress. I felt quite desperate and lost, unable to fund refuge amongst the refugees. …

Hut No. 37, which was to be our abode for nearly a month, was a longish wooden structure, divided by a wall in the middle into two parts. Each part contained two rows of double bunks, a long table and two forms, and an iron stove. Now, in retrospect, that clean and spacious hut, with clean sheets and blankets on the beds, seems to me the most comfortable hut I have lived in in the three years of my Army life. But at the time I moved into it I thought it impossible to live in such a place, let alone sleep. If only one among us twenty were in the habit of snoring, which was more than likely, how on earth could the remaining nineteen sleep, I wondered.

Together with Kaye I investigated the washing and toilet accommodation. There were a number of ablution huts, quite well appointed by military standards, but utterly inadequate for people used to private bathrooms. There was about enough room in the ablution hut for a dozen men to wash simultaneously … “Perhaps we can arrange for an occasional bath at one of the Sandwich hotels.”

Our next visit was to the toilets. Strictly speaking, latrine would be a more correct term for the accommodation we found in the place of toilets: a row of seats in a brick-enclosed réduit, the seats partitioned off by flimsy, transparent-canvas hangings; needless to say that there were no doors to ensure a semblance of privacy. …

We went back to our hut and began making our beds. The hut was crowded with new recruits, all smoking and talking together excitedly. …

There was a dismissal parade at four o’cock, and soon afterwards a bugle call summoned the troops to tea. … I seconded the motion to have a last, luxurious farewell meal in Civvie Street, followed by a few rounds of drinks.

Sandwich was within easy walking distance. The road to town was straight and slightly uphill, which was all to the good, Gorloff commented, as it naturally followed that the way back to camp must be downhill. … “A hangover in Kitchener Camp must be the most frightful thing imaginable.”…

It was a little after five when we arrived at Sandwich, a bit too early for dinner, but the pubs were about to open. For a while we walked about the streets, taking in the scene. The sun had been shining all day long, the air warm and fragrant of spring; the trees were in full leaf, and the birds insane with some inexplicable joy. So far as I could make out, Sandwich was an agreeable little town, half asleep with peace and opulence, and there was a certain old-world charm about some of the Tudor houses, especially around the market place.

There were a number of pubs, two picture palaces, and two or three hotels in the town, the best of the latter being out of bounds to O.R.s. …

The next day was a busy one. All the newly arrived recruits were to be interviewed by the O.C., and drafted to the various companies in training. We were also to be issued with our army kit.

The interview did not take much time. We were lined up in strictly alphabetical order outside the Company office. Lieutenant-Colonel the Marquess of Reading was at the time Officer Commanding No.3 Training centre A.M.P.C. As a matter of fact, it was he who, a few months previously, had been entrusted with the task of forming the No.3 Centre, which was exclusively composed of aliens. Lord Reading was assisted by a number of officers who, for some reason or other, were considered particularly suitable for dealing with the alien personnel. I remember Captain Birrell, Lord Reading’s adjutant, a tall, military figure, who impressed me so much that it took me several days to find out that he was not the O.C. himself but merely his adjutant. There were Major Chauncey, O.C. No. 1 Training Company, to which I was to be drafted, almost as short as Captain Birrell was tall, but whose voice on the parade ground sounded like trumpet-blasts; Major Stork, then O.C. No. 2 Training Company … a man in the middle forties, worldly, suave, friendly …

Outside, several clerks took down my particulars for the nth time. When they were satisfied at last, I received, in exchange for my passport, registration papers, and civilian ration card, a number which henceforth was to be my Army number, 13802023.

I remember, too, that as soon as we had our army outfit, we were assailed by a swarm of second-hand clothes dealers eager to acquire our civilian suits for next to nothing. Hoping that we were hard up for money, they offered something like three or five shillings for a suit of clothes. I was disgusted by this trade, the more so as the traders were no outsiders but refugees from the adjacent camp. These vultures, trying to make a profit out of their fellow-refugees, were not easily discouraged: they insisted, and on being told to go to hell, increased their offer by sixpence. I had intended to give my clothes away, but under the circumstances I made a bundle of the stuff and dispatched it to London.

Early in May the war started with a bang. Up until then, and with the exception of Poland’s subjugation by the German hordes, it had all been a matter of skirmishes, patrol duels, and nerve warfare: the British dropping leaflets on Germany, telling the Germans what a scoundrel Hitler was, and the Germans dropping leaflets on France, telling our allies what our (British) intention was: namely, to fight to the last Frenchman.

It was radiant spring in Kent, and the war – the reality of war – seemed far, very far removed. …

An enormous pincer movement threatened Paris. The capital was declared an open town, and surrendered away or two later. the germans were fanning out in Normandy … And a few weeks later came the grand finale Dunkirk.

Long before it came to Dunkirk, the events were viewed with great concern in my Company. the alien Pioneers were clearly pessimistic about the course of the war; more than pessimistic – they were panic-stricken, scared to death. Germany was on the march, and they knew that no power on earth could stop her. They knew that Germany would be in possession of the whole of Europe before the summer was over. They knew that Britain was doomed, the country invaded and subjugated, like the rest of Europe – and the world. And knowing that the war was practically over, and lost, they naturally enough trembled for their lives.

From the refugees’ point of view the worst apprehensions seemed justified. They had lived all their lives in Germany, and knew the ruthless force of the German military machine, the admirable organisation of the Wehrmacht, and the powerful Luftwaffe, built up over a number of years while Britain was asleep, or just rolling over in bed, yawning. … The refugees did not believe in miracles; they believed in the might of hammer-blows. They had all suffered at the hands of the Nazis, and now they were horrified at the prospect of again falling into their enemy’s hands. This time it meant certain death; there was no escape possible. …

“The trouble with the British is that they haven’t the faintest idea what they’re up against,” said someone else. “They know the Nazis by hearsay only … they’ve read about them in the papers and in books, but they don’t realise how efficient the devils really are!”

There was some truth in that. The fears that obscured the minds of the Pioneers were well founded in fact. These men were desperate, because they knew, from their own experience, all the atrocities of the which the Nazis, unloosed, were capable. Nearly every one of them had been subjected to the cruelty and brutality of the Hitlerites. Had they actually been captured – or rather recaptured – by their oppressors, their worst fears would indeed have come true.

The English, on the other hand, had never experienced this fear. They were apprehensive, of course, of the war situation in general, but they were not really afraid … not physically so, anyhow. Their nerves were not rattled. Their very ignorance of the thoroughness of German native brutality, which none of them had experienced in the flesh, as it were, saved them from the panic with which the victims of Nazi oppression seemed to be seized. For the refugees, fight was out of the question: in their hearts they declared themselves beaten, and their sombre speculations as to the fate that awaited them were of a purely technical nature: by what means were they going to be exterminated – by hanging – shooting – or being whipped to death. …

Had the English actually known, as the refugees did, the terrible tortures and ordeals in store for them should the Germans be able to get a foothold in these islands, they too might have lost their heads and given in before the struggle for life and death was actually to take place. .. England could resist only because the English had no idea what they were in reality resisting, nor how heavily the dice were loaded against them.

The general outlook in the camp was distinctly black, the attitude of the Pioneers clearly desperate and defeatist. And although I could not share their pessimism I somehow could not blame them for it. That fellow, for instance, who resembled a gargoyle had only become a gargoyle in a concentration camp. Before Hitler marched into Czechoslovakia he was an engineer, and probably as normal as you or I, thought it is difficult to imagine the tortures which could change an ordinary human being into a crushed worm.

There was another former inmate of a concentration camp in the Company, Achatpart by name [editor: all names were changed in the book]. He had been a lawyer or solicitor in Vienna, and was arrested and thrown into a concentration camp as reprisal for the assassination of some attaché at the Paris German Embassy in 1938. Achatpart had lost his humanity in Dachau and become an insensate brute. I often observed him at a distance. He rarely talked to anybody, standing apart from the others, brooding and ruminating the past. … He was a hard worker, too, working even when no NCO was near by, for he had been nine months in a Dachau working party. I believe his mind was a bit muddled, and he was clearly suffering from a fear-complex. He gave the impression of a haunted shadow. When he worked he did so feverishly, as though he felt an SS man was standing behind him, whip in hand. When spoken to abruptly he would jump to attention, even though his interlocutor were a simple recruit. Often he would go for little walks, hiding himself from the crowder he would just stand and stare in front of him for hours on end. He never laughed or smiled. Achatpart was a man from whom all joy of living had been whipped out; he was sensitive only to shouts and blows. A good enough corpse alive as any.

To people like these it as natural that things looked hopeless. it would have been useless to argue with them; I could never have given them courage. Besides, never having been in a concentration camp myself, I had no say whatever. I was as daft and as ignorant as the English.

“Why should you worry, anyhow?” Gertenzahn, who was later drafted to Section 5, would often say to me when I made fun of the prevailing pessimism. “Nothing is going to happen to you; they won’t kill you. Why, you’re not even a Jew! You’re like the English. You’ll lose the war all right, but what of it? Can happen to any country. But what shall I do? There’s no way out for me.” …

There was a wireless in the hut, and three times a day the section listened to the news in church like silence. A man risking a cough while the news was on got poisonous glances from the whole section. Needless to say, they did not listen only to the BBC, but to enemy stations as well. To Lord Haw-Haw they listened with consternation, feeling that every word he said was not only true, but a menace to them personally. The alien pioneers could never understand the nonchalance with which British soldiers kept laughing, chattering, or playing darts or ping-pong while the news was on in the naïf canteen. It was shocking to them – shocking and stupid. …

If the civilised man does not precisely live to eat, he enjoys good food all the same. And a man used to cuisine, especially cuisine française, must view the prospect of Army food with some concern. As everybody knows, the Army rations are plentiful, and, generally speaking, of good quality; and if the stuff gets spoiled, as a matter of routine, in the cookhouse, what’s the use of blaming the cooks? No one expects them to produce particularly refined dishes. Cooking for a company of some 300 men is like cooking for a soup-kitchen. From the Army point of view, the essential is that the men get enough to eat, and no one asks what it tastes like. That, at least, was what I anticipated when I enlisted, and I was resigned to the worst. I was greatly surprised to find the food excellent. …

None of the Company cooks were professionals, but they were Continentals with an innate taste for food. Our menus were strongly reminiscent of those of the various Hungarian, Czech, or Austrian restaurants of Soho. I have subsequently been attached to British units, and I will truthfully say that our own cuisine compared rather favourably with that produced by the natives of these islands. There was one item, though, in which our cooks nearly always failed: tea. Tea is invariably better in British companies. …

……………….

We had had our inoculation, followed by a couple of days off duty, and we were impatiently expecting embarkation leave prior to leaving for France. It was then that the Germans began their offensive against the Low Countries and France. Things happened in such rapid succession, as everybody remembers, and within a few weeks the situation became so grave that it seems pointless to dispatch any more AMPC companies to France at a time when our troops were already retreating towards Dunkirk. …

The invasion danger, up to then purely theoretical, suddenly became acute. Were the Germans to gain a foothold along the coast across the Channel, it seemed a safe bet that they would attempt the invasion Britain. All Army leaves were stopped. Richborough, being such a short distance from Dover, had almost become front-line; it was no longer a suitable place for a Training Centre. Within a few days of the German onslaught we left.

……………….

There was another NCO in my working party, a lance-corporal, Ison Kepler by name. From East Prussia, he was tall, athletic, and of considerable muscular strength. A dental mechanic by profession, he had made a comfortable living in Königsberg until the Nazis, on coming to power, drove him away, on racial grounds. Kepler was soon to become a full corporal, and he was liked by everybody in Section 5. He was just and kind-hearted, and it was easy to get along with him. He had no rancour or resentment against anybody, treating us all alike, with sympathy and understanding; he was the ideal link between us privates and Sergeant Whiting.

Unfortunately, he knew hardly any English; he was one of the earliest volunteers to the AMPC, having enlisted in Richborough, were he had been in the civilian refugee camp. Naturally, he did not learn much English there, but he was now picking it up fast. Although his accent was atrocious, he refused to speak German.

……………….

There were already symptoms pointing to a break-up of the Company in the near future. For some reason or other, the 137 Coy. was considered – or perhaps, merely considered itself – as an élite company, and the men began to resent being Pioneers – just navvies. They were far too good for that, they imagined. They had all volunteered for the Pioneer Corps, of course, but as time wore on their vanity was aroused. Why couldn’t they be in the RAF, the Navy, or the Intelligence Corps, they asked themselves, more loudly every day. They considered the Pioneer Corps an inferior branch of the Army … and they increasingly applied for transfer to other Army units. Nearly all were impatient to get out of the Pioneer Corps, and they could not understand why, despite their high educational standard and evident qualifications, the War Office should be so reluctant to grant them transfers to other units, where, they felt sure, their special knowledge could be used to far greater advantage in the war effort.

The reason for the War Office’s reluctance to grant those transfers was, of course, rather obvious. Why should the War Office trust the alien Pioneers? After all, most of them were Germans, or of other enemy alien origin. They called themselves “refugees from Nazi oppression,” and that’s what they were. But how were the authorities to check up on each individual case? What would deter an enemy agent from masquerading as a “refugee from Nazi oppression”? Nothing would have been easier for the German Intelligence Service than to make some of their crack spies pass as oppressed refugees. In the Pioneer Corps they could not do much harm, the most dangerous spy being harmless as long as his activities are reduced to digging holes in the soft soil of Somerset. But to use them, say, in the British Intelligence Corps, would have been an altogether different matter.

……………….

It was drawing towards the midday interval. The sun stood almost in the zenith. I was stripped to the waist, rubbing Nivea cream into my skin. The sun gets pretty hot in Somerset in June. Our tan was turning chocolate-brown and the legs of those working in shorts were the colour of Havana cigars.

My working partner happened to be Achatpart, the ex-inmate of Dachau. We were supposed to pump water to a distant concrete mixer, which was an easy job, as the pump was a semi-mechanical one.

Achatpart was apparently still under the spell of the Gestapo treatment he had to endure in the concentration camp. A hard worker, he never hesitated to obey an order, but carried it out instantly, as though he were still afraid of the SS whip. He had been told to pump water, so he pumped water, regardless of the fact that the water tank at the other end of the hose was full up. No one had given a counter-order, so he kept on pumping. Nor did he take off his fatigue blouse and shirt. He sweated like a horse, but kept on working fully dressed. I asked him if he was hot, and he admitted that he was.

“Why, then, don’t you take off your shirt?” I asked.

“I don’t think we’re supposed to,” he answered. … “I don’t want to get in any trouble,” Achatpart said. “I’ve had all the troubles I want. Doesn’t pay not to obey orders.”

He kept on pumping assiduously, and I watched him for a while. He was intent on his work, but it was quite evident that he was not working for the sake of work, but merely to avoid the punishment which, to his distorted mind, would be forthcoming the moment he relaxed. …

“Relax, Achatpart, it’s an order,” I said. “And for heaven’s sake, take that persecution-complex look off your face. No-one is going to hurt you here.” No answer, but he took a huge khaki handkerchief out of his pocket and began mopping his brow. “Look here, Achatpart, I want to talk with you. You haven’t spoken to a soul for over a year now. I know, I’ve watched you. You work like a madman and you act as if the whole world were in conspiracy against you.”

Achatpart apparently failed to understand what I was talking about. But he realised that I was not a fiend waiting for the appropriate moment to fall upon him with a club. …

“What do you want?”

“Nothing. I just want to be friendly with you. … You’ll go mad if you keep this up much longer. In your mind, you’re still in Dachau. Don’t you realise this place is miles and miles away?”

Achatpart gave a shrill laugh. He was not used to laughing. This was the first time I heard him laugh, and his laugh frightened me. …

There was no good answer. Achatpart was a man possessed … How indeed was he to cast the devil out of his body? It was hopeless without outside help. But what could I do? … I had read a lot about psychoanalysis, but perhaps he was too far gone for psychoanalytical treatment. I decided the best thing was to make him talk. …

“The moment you talk about it with someone, the load comes off your chest. And that’s what you want, don’t you? Get it off your chest.”

“Surely you don’t want me to talk about these things. … Don’t make me talk … please don’t. I promised not to. If they ever found out I’d been talking, they’d kill me. They said they would. You don’t know them.”

“Never mind those rats. You’ve nothing to fear. Their reign is over. Soon they’ll be worse off than you ever were. They’re already trembling … Tell me all about it, Achatpart. I promise you’ll feel heaps better afterwards.”

“Even if I wanted to talk about it, how could I? It isn’t a story I have to tell, with a beginning and an end. It’s all so confused and disconnected, like a nightmare. It wouldn’t make sense to you. It only makes sense to me as long as I don’t try putting it into words. The moment I do, the whole thing becomes unintelligible and nonsensical. There are certain things one just can’t talk about. … Perhaps some day … I’ve got to think it over. Not right now.”

……………….

This time, Achatpart began talking all by himself. No coaxing was required. …

“You worry about my health, don’t you?” he said, with the beginning of a grin. “There was that fellow who used to worry about out cleanliness. Bathing parade twice a week, and what a bathing parade that was! The rat regulated the water to the temperature he thought was best for us. You stood under the shower to attention. You always stood to attention before those rats. He let the water go either icy or scalding, according to the mood he was in. If he didn’t like your face, you could consider yourself happy if you came out of the cubicle with the skin over your flesh.” …

“I shall remember the winter ’38 for some time … I was a freshman in Dachau then – had only just arrived. You want to know why? But there is no why – no reason. I was walking to my office one morning, as I had done for the last twenty years. I was stopped in the middle of the street by two Gestapo dogs. … They took me straight to the station – the railway station, not the police station – and I was thrown into a cattle truck. I wasn’t the only one. There was a long goods train, all loaded with Jews. We were eighty or a hundred to each truck, and the bastards locked us up, worse than cattle. There was no room to stand, or move, or breathe; we were just lying on top of one another, bruised and half choking. It’s a long journey from Vienna to Dachau, and never once was the truck opened! Never once were we given a crust of bread or a drink of water, or a breath of air. … I don’t know how many of us survived the journey, but those who did were dumped outside the camp gates, all in one heap, like so much stinking refuse. Naturally we were all dazed, numbed … too sick to get up. What a feast that was for the dirty SS hounds! They fell upon us with rubber sticks, clubs, and whips, and they made us get up. Individually, we were made to run through a double row two hundred yards long of SS swine armed with heavy sticks, and we had to run for our lives: the quicker we ran the fewer strokes we received. Only the young and tough ones got out of the ordeal alive – the others were beaten to pulp before they got inside the gate with that noble inscription: ‘ARBEIT MACHT FREI.’ That was our initiation, and the beginning of a life of hell.”

……………….

“Nine months. But that again doesn’t mean anything. I might as well have been there nine years, or nine hours, or ninety years. This is something you can’t understand. You don’t measure time in a concentration camp by normal standards of measurement. In Dachau time was measured by the intensity of suffering. Every minute was an eternity. It’s meaningless and tragic. … One night, I remember, we had just gone to bed when the whistle summoned us to the courtyard on parade. The whole camp had to parade. I don’t know how many thousands. … we had to stand to attention till the following morning. Hundreds of searchlights were trained on us – and a few machine-guns as well. It was January, in sub-zero temperature. The SS dogs, clad in heavy, fur-lined coats and snow boots, were running up and down to keep warm. As for us, we stood to attention all night in shorts and shirt-sleeves. If you made the least move, one of the SS swine knocked you down with his fist or pistol-butt. Those dogs didn’t require much encouragement to kill you. If the poor devil next to you collapsed in a faint or dropped dead, you were not allowed to help him.” …

“Escape was out of the question. The barbed wire around the camp was electrically charged, and touching it would have meant instant death. But you never got as far as the barbed wire; the machine-guns got you first … Life in Dachau wasn’t worth living, but men cling to life no matter how miserable.”

……………….

“Any one of those swine had a perfect right to kill us, without any questions being asked. Killing a Jew was no more reprehensible an act than crushing a louse between the fingers. … The camp crematorium was always at work. One day your mother, your wife, or sister received a post card with the laconic message that Jew So-and-so was dead and that his ashes were obtainable for the modest price of ten marks.”

……………….

“How did you get out of Dachau? When were you released?”

“Just a week before the outbreak of war. I know I am lucky. I had some relatives in England who obtained a visa for me. I got out of it in the nick of time. I dare say those who remained are dead by now.”

……………….

But to come back to the alien Pioneers, gentlemen. They have changed a good deal since the early days of Richborough. For one thing, they speak English now. Even the most inveterate ‘Balkanese’ have a smattering of English. Naturally, they still fall down on the tenses and the subjunctives, but so do our British sergeants. They know all the more important albeit unprintable, one-syllable words, and they make liberal use of them.

What is more important still is that they are no longer a cowed and hopelessly despondent lot: they have at last conquered their fear of the Nazis: they no longer believe that Hitler can win the War: they have a hunch that their plight is over. No more pessimism on the part of the alien Pioneers! On the contrary, they are almost lunatic with optimism: there are a few who think the War will last another six months: some swear Jerry will crack up in March or April ’44, at the latest. My old friend Gertenzahn, who four years ago was convinced that Hitler would come to Richborough personally, for the sole purpose of cutting off his ears, gives the Führer till Christmas to do a spot of hara-kiri. Sein Mund zu Gottes Ohr, gentlemen, what? Naturally, I do not share their optimism any more than I did their erstwhile pessimism. … No, gentlemen, your alien Pioneers no longer worry about the outcome of the war; but since worry they must, they worry what will be their fate after the war. Will they get British citizenship? Will they be allowed to take up residence in this country? Will they be permitted to work? …

They do seem to want these things badly. If you listen to them, their very lives depend upon British citizenship. Throughout their existence they have been worrying about nationality and passports, or lack of nationality and lack of passports. Some have become nervous wrecks … Why don’t you give them what they are convinced would make them happy? It wouldn’t cost you much, and I believe they deserve it. … I don’t think you will get rid of your aliens easily: they are going to cling to you. They have struck root in your fair island: they are yours for keeps. … Let them have those bloody passports for which they are clamouring: it’s the second best thing you can do: the best would be to do away with passports altogether. You have already given them Registration Books and AB 64’s (Parts I and II); you have even permitted them to change their names for wonderfully-sounding British equivalents! Believe me, gentlemen, they have taken advantage of it! …

Of course, the war is not over yet. The alien Pioneers, many of whom are already in various eminently combatant units, may still have the chance for which they have been waiting for years – namely, to show their mettle in combat. … You cannot loathe the Nazis as much as they do. They are intelligent, exalted, and replete with fanatical hatred for Hitler. They will put up a good show.

……………….

ALFRED PERLÈS

25th November 1943