Born: Halle an der Saale, Germany, 28 December 1922

Occupation in country of origin: Mechanics trainee

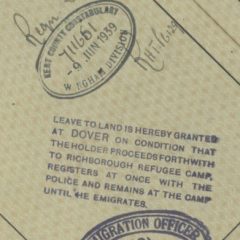

Arrived in Britain as a refugee from Germany on 29 August 1939

Documents

Memories

My father Ernst Loewenberg was born in Berlin on 28 December 1922.

Ernst was a mechanics trainee with the Berlin ORT. He came out of Germany to Britain with the school in August 1939. He was with his school friends in Kitchener camp for around 6 months before they were transferred to Leeds, where a new ORT School had been opened.

During the war Ernst helped build Spitfires in a factory.

His family name is also Levenbergs – my grandfather was a Latvian Jew.

The following links provide further information about Ernst Loewenberg and the ORT boys:

- A short clip from a BBC documentary with Harold (Harry) Rossney, Felix Burnell (Bujakowsky), Ernest Lowenberg, and Kitchener author Clare Ungerson.

- An interview with Ernest Lowenberg can be viewed here at USHMM.

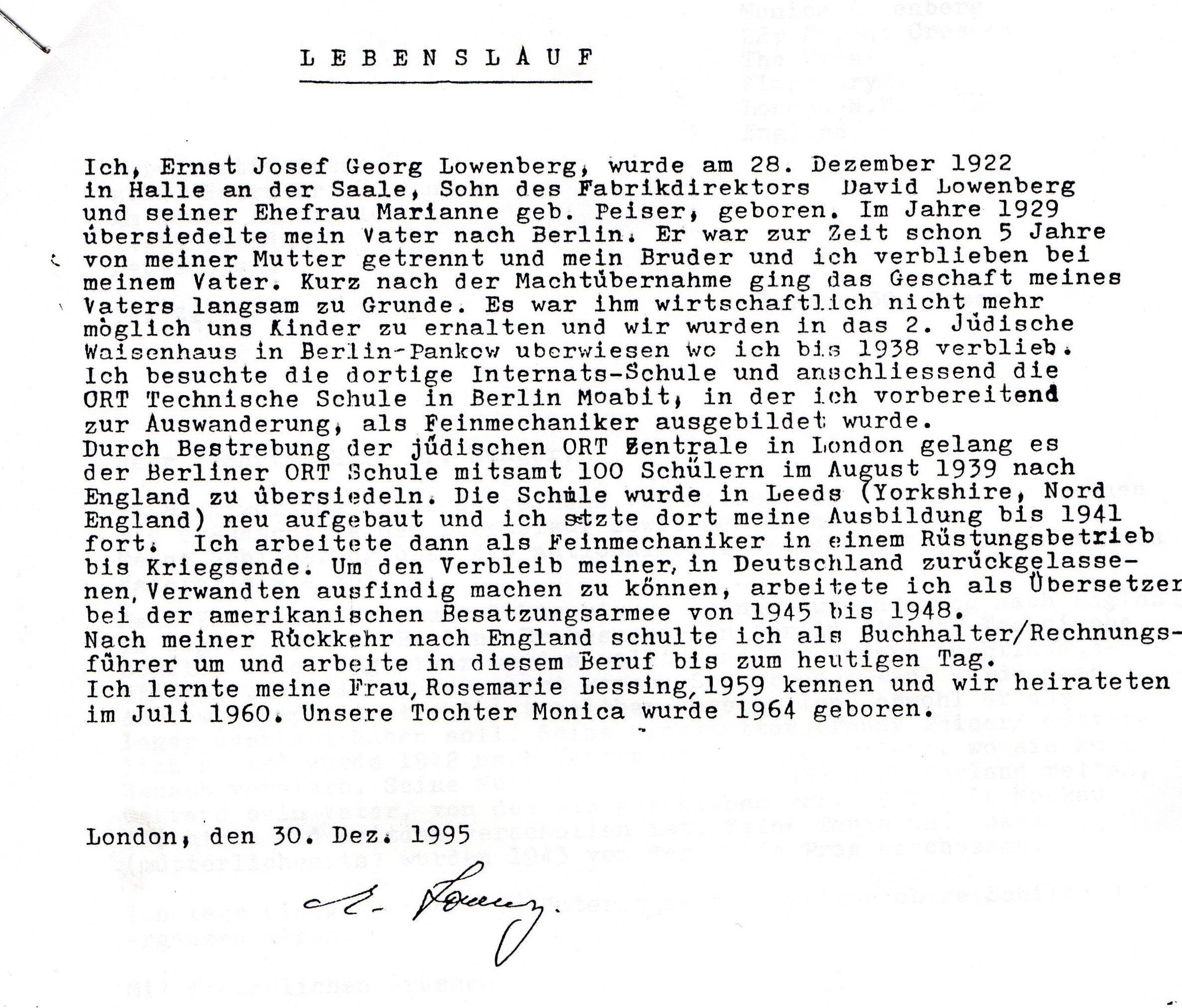

On 30 December 1995, Ernst’s daughter Monica asked her father to tell her something about his life, for he had lived through probably the most traumatic and historic of times the world has ever known.

He typed a statement, in German, with no reference to Hitler and the National Socialists. It was 24 lines long, and reads as follows (in translation)

I, Ernst Josef Georg Lowenberg, was born on the 28th December 1922, in Halle an der Saale, son of the factory owner David Lowenberg and his wife Marianne nee Peiser. In 1929 my father went to Berlin. He had for the past five years been separated from my mother, and my brother and I stayed with our father.

Shortly after the takeover, my father’s business slowly came to a halt. Financially, it became impossible for him to look after my brother and me, and so we were taken to the second Jewish orphanage in Berlin Pankow, where I stayed until 1938. I went to the boarding school there and then to the ORT technical training school in Berlin Moabit, where I was prepared for evacuation and trained as a mechanic.

Due to the efforts of Jewish ORT in London it was possible for the Berlin ORT School, with 100 pupils, in August 1939, to move to England. The school was built from scratch in Leeds, in Yorkshire in the North of England, and I continued my training there until 1941. I then worked as a mechanic, helping to make Spitfires until the end of the war.

To be able to find out what had happened to the rest of the family, who had stayed in Germany, I worked from 1945-1948 as a translator for the American Army. On returning to England I trained as a book keeper/ accountant and worked in this profession to this day. I got to know my wife Rosemarie Lessing in 1959, we married in 1960, and our daughter Monica was born in 1964.

The Education of the Cologne Jawne Gymnasium Children and the Berlin ORT School Boys in Germany and England

A talk by Monica Lowenberg

Life in Germany

From their rise to power in 1933 and World War II the Nazis had managed in only six years to create four hundred laws and edictsagainst Jews.Laws that the Nazi’s zealously executed until their final defeat in 1945 and which were ultimately bound with the overall aim of totally ghettoizing and secluding Jews from the wider community and eventually eliminating them all together by emigration and extinction. It is estimated that at least twenty of these regulations were concerned with the education of the Jewish child in Germany.[1]

For Jewish children the degree of persecution they suffered depended very much on where they lived, their relations with their German neighbours, and size of the Jewish community. It is safe to state, though, that the situation of the Jewish child in a very small Jewish community was worse and was a deciding factor for them and their parents to move in some cases. In small towns and villages, Jewish families and their children tended to become completely ostracized from non-Jews. Friendships that they had nurtured for many years were almost over night abruptly terminated, leaving them to fend for themselves as they became the subjects of mockery and beatings.

Jewish children brought up in the cities could also relate similar stories of cruelty, teachers relishing in the theory of ‘Rassenkunde’, excluding them from sports shouting, ‘Jews can’t do gym; they are useless; go in the corner,’[2]making the child’s life so unbearable that to leave and attend a Jewish school became for many their only option. Nevertheless, it would be wrong to assume that all German teachers were in favour of the hostility and racism that was nurtured within the school environment: a number were not, but they saw resistance as being simply too personally dangerous. As one pupil recalls who eventually left his school to attend the Jawne Gymnasium,

My mother went to the school and said to the class teacher that there was so much bullying that she would have to take us away and he said, “I know and it is more than my job is worth to stop it”. And she said he was in tears.[3]

Not only did the Jewish child have to contend with a high degree of unrest at school, but in their domestic situation as well. The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 paved the way for the complete exclusion of Jews from intellectual, economic and social life in Germany ensuring that the lives of all Jews, children and adults became increasingly intolerable. As one Kindertransportee, Hilde Schoenfeld, describes, ‘Germany was like an octopus with tentacles coming all around you; in the end you couldn’t breathe anymore’.[4]

Numerous children witnessed their parents slowly slide into utter desperation as they were forced to sell up their businesses, sell their stock at laughable prices and in the worst cases sent to concentration camps after 9 November 1938 – the night of broken glass (Kristallnacht).In most cases the fathers returned, but showed visible signs of severe beatings and trauma that only heightened the atmosphere of anxiety that the child daily breathed. Rolf Schild’s father was taken to Dachau for two to three weeks. When he returned, ‘he didn’t talk about it, but spent six months living on a barge, was many nights away to avoid being arrested in the night.’[5] Tragically the fear of being caught and further persecuted very often remained even once parents and children had left Germany,to the extent that one Jewish mother once in England kept poison in a cigarette holder in case Germany won the war.[6]

The Order of September 10, 1935 demanded that all Jewish pupils be expelled from Aryan schools; consequently, the number of Jewish pupils attending Jewish schools literally doubled from ten thousand in 1933 to twenty thousand in 1935. In Berlin it has been estimated that approximately four thousand expelled Jewish pupils subsequently attended Jewish schools; many spoke of the relief they felt to be able to go to a Jewish school where they were finally accepted and allowed to ‘be themselves’. In 1935 Jewish teaching personnel totalled 1,057, an increase of two hundred and forty-four since 1933. However, there was a shortage of physical training teachers, and in commercial and technical subjects. In the same year forty four thousand Jewish pupils were enrolled in all types of schools. It is important to note that twenty thousand, or 45.5%, attended Jewish public schools, junior and senior high schools, and the remaining twenty four thousand, or 54.6%, continued to attend German schools through high school, despite the order to have them expelled.[7]

Two years later, according to a survey conducted by the Reichsvertretung, the total number of Jewish pupils in the German Reich was reported at 38,632,a decrease of approximately five thousand. The drop in Jewish pupils was undoubtedly a consequence of emigration, deportation and mortality.[8] On December 17, 1938, the Reich’s Minister of Educationannounced the cessation of support of Jewish schools. However, blatantly at odds with this order the government continued until 1939 to give subsidies to Jewish elementary schools, paid part of the taxes back to the Jewish community, and paid teachers’ pensions. The legalistic mentality of the Nazis is laughable when one considers that on one hand they persecuted German Jews mercilessly and on the other met their financial obligations and helped in the education of Jewish elementary children.

Under such fraught circumstances the task of educating Jewish children became increasingly difficult. School staff were not only obliged to contend with the new states orders, malicious propaganda, daily changes in class sizes as a consequence of internal immigration and emigration,[9]but also to accommodate basic changes to their teaching habits to meet the new demands and needs. Such alterations entailed:1. placing greater emphasis on training in Judaism and the Hebrew language.

- 1. placing greater emphasis on training in Judaism and the Hebrew language;

- 2. persuading and transforming indifferent children into pro-active Jews by making them participate in celebrations and activities within a Jewish context;[10]

- 3. preparing them to deal with their fragile position in the Nazi world;

- 4. preparing them for emigration; and

- 5. giving them a vocational training which could be used in the country they were emigrating to.

Against this backdrop the ORT school children were educated.[11]

The ORT School

ORT Organization for Rehabilitation Through Training, or Obschestvo Remeslenovo i zemledelcheskovo Trouda, was founded in Tsarist Russia in 1880 by Samuel Poliakov – a financier and railroad builder who with four other Jewish businessmen and residents of St. Petersburg was committed to the general improvement of conditions for Jews in Russia and their integration into Russian society. ORT’s primary aim was to train young people in manual trades and agriculture.[12]

The first ORT vocational school was opened in Berlin in 1937 with the help of German ORT and the World ORT Union. However, between the years 1931 and 1934, ORT had already established in Berlin seven vocational courses providing training in woodwork, motor repair, and other crafts. The plight of German Jewry became obvious when some 200 unemployed former physicians, lawyers and clerks enrolled for these courses. As Shapiro states, ‘The establishment of the school at this particular time, aside from its practical importance, was a demonstration on the part of the remnants of German Jewry of their will to survive and resist’.[13]

The school, located in an empty factory in the north west of Berlin, Siemenstrasse 15, offered vocational training to Jewish youth between the ages of 15 and 17 – boys who were unable to attend a state or municipal trade school. 101 students were enrolled for training in woodwork, two thirds of whom came from Berlin, and 13 adults in courses in gas and water plumbing. Louis Wolff , the last chairman of ORT Germany before the second world war, stated that the total number of pupils or ‘Lehrlinge,’ as he named them, attending the school was by the end of 1938 in the region of 200, and administration and teaching staff approximately 20.[14]

The Berlin technical school, or ‘Private juedische Lehranstalt fuer handwerkliche und gewerbliche Ausbildung auswanderungswilliger Juden der ORT Berlin,’ was heralded as the most important institution of professional training for German Jewry and apparently allowed to open with Adolf Eichmann’s personal consent on the condition that it was exclusively for Jews who were willing to emigrate.[15] The school had a curriculum of 3 years and the courses for adults were reduced to 18 months. Officially founded by the British ORT, the school was subsequently under protection of the British government and the only institution that remained unaffected by the violent events of November 1938.

The board of the school was headed by civil engineer Hans Behrendt, who had worked for many years in various industrial enterprises and had administered his own factory.[16]Many of the pupils had prior to attending the ORT been studying at non-Jewish schools and some gymnasiums. For those pupils from outside of Berlin, not only did they have to rapidly adapt to life in the city but to sharing dorms with a number of other boys in a hostel which was inspected by the Nazis.[17]

At all times, the hostel was controlled by the Nazis. The uniformed policemen would come, without prior notice, to inspect the hostel. The beds had to be made in the same way as in the army. They would also check all the wardrobes and toilets and push us around all the time. The laws of the hostel were strict, order and discipline had to be kept up within the house. Members of the hostel were from many different social backgrounds. The only thing they had in common was their Jewish background and the wish to study something in the engineering trade which would enable them to find a job outside of Germany.[18]

A number of boys spoke of the pleasure and sense of satisfaction they found in learning a craft. Helmut Gruenewald decided to become a toolmaker under the watchful eye of Max Abraham – a former employee of the machine factory Ludwig Loewe, who had dismissed him on the grounds of being Jewish.[19]

I liked the work on the bench very much, learning at school less. Soon, one of my teachers told me, “Gruenewald, you will pass the practice examination very well, but in respect of the theory, I am not too sure. But the first examination would turn out very different. Due to the splitting of the tool I was producing during the hardening process, I only received the mark 3. Whilst in respect of the theory, I was lucky in being asked a question whose answer I knew very well. So I received the mark 1. This mark surprised the teachers and fellow students.[20]

On the eve of war Col J. H. Levey of British ORT came to Berlin to obtain permission to transfer the school plant, which had been purchased on behalf of the British ORT, its students and teachers, to England. In the last moment, the Nazis refused to have the equipment removed, severely stalling procedures to transfer the students and their teachers. Finally, the British consented to the transfer taking place without the equipment. A total of 106 boys between the ages of 15 and 17, with eight instructors and their families, left Berlin for England on August 29, 1939. It was one of the last transports out of Germany. A further transfer for the remaining 100 or so ORT boys and school director Dr. Werner Simon was planned for 3.9.39, which was tragically too late: the majority of this group perished in the Holocaust.

As a consequence of the German authorities’ refusal to allow the schools’ plant to be transferred, arrangements regarding accommodation for the students and staff in Britain had not been made. Temporary accommodation had to therefore be found for the male staff and students at the Kitchener camp in Kent, and the women and children were sent on to Leeds where the schooling of the Berlin boys was to be resumed. During the two-month period that the boys spent at the camp they developed their English skills by doing odd jobs for the locals, filling sandbags and picking apples.[21]

By November 1939, the same boys, under the guidance of their instructors from Berlin, installed the machinery, connected it with the electric power supply and made all fittings possible in the workshop of the school. The students of the plumbing and sanitary section of the school erected lavatories and wash houses and within a short time the school was up and running. The Leeds ORT school was divided into five sections or departments:

- 1. Welding, Turning and Fitting

- 2. Sanitary Engineering

- 3. Electrical Engineering

- 4. Mechanical Engineering

- 5. Carpentry and Joinery

The training consisted of both practical and theoretical work, and all lessons were given in English. In the practical section students learnt methods of working with metals, wood, tools, and machines, and in theoretical, subjects such as mathematics, physics and geometry. No religion was taught in the hostels where the boys lived,[22]but arrangements were made for classes to study Jewish education and additional evening classes in English. As the Leeds ORT stated in their prospectus, “We are a technical school, not a religious educational establishment’.[23]

Some of the students had only started to attend the Berlin ORT school in the year before emigration and therefore had not acquired technical skills that were sufficient for entering the respective trades they wished to pursue. Nevertheless, time spent at the Leeds ORT enabled them to fully complete their studies and be suitably well qualified. In some cases their Gymnasium education had been severely disrupted, but they had been given the opportunity to finish their studies in a stable environment with individuals they knew.

Notes

[1]Solomon Colodner, Jewish Education in Germany Under the Nazis (New York City: Jewish Education Committee Press, 1964) p. 37. For a detailed list of all the laws that affected Jewish youth and their education see pp. 37–39.

[2]Interview with Hilde Schoenfeld Kindertransportee from Berlin and former pupil of the Zweites Waisenhaus school in Pankow; Personal Interview, taped. 2 July 1998. London.

[3]Interview with Ralph Blumenau, former Jawne pupil. Personal Interview, taped. 12 March 1998. London.

[4] Interview with Hilde Schoenfeld. Personal Interview, taped. 2 July 1998. London.

[5] Interview with Rolf Schild, OBE; former Jawne pupil, Cologne . Personal Interview, taped. 7 July 1999. London.

[6]Interview with Ralph Blumenau. Personal Interview, taped. 12 March 1998. London.

[7]Colodner, Jewish Education in Germany under the Nazis, pp. 44–45.

[8]Colodner,Jewish Education in Germany under the Nazis (p. 53) summarises that in 1937:

- 1. Of the reported 38,632 Jewish pupils, 23,670 (61.27%) were enrolled in Jewish schools.

- 2. About 18,000 attended Jewish elementary schools and about one-third of all children attended these schools.

- 3. More than half of the Jewish schools were elementary schools and about one-third of all children attended these schools.

- 4. About two-thirds of Jewish pupils in high schools attended Jewish schools.

[9]After the assassination of a Secretary of the German Legation in Paris, Ernst vom Rath, Jewish emigration increased fivefold. By November 1938, 100,000–150,000 Jews had left Germany: 40,000 were allowed to enter Britain, a quarter of whom were children coming under the umbrella of the Kindertransport. The Jawne Gymnasium children and Berlin ORT school boys came under this number. According to the Central British Fund for World Jewish Relief exactly 9,354 children were saved. Youth Aliyah under the directorship of Arieh Handler managed to save a further 10,000 children, 3262 of which were German Jewish children sent to Palestine where they worked on Kibbutzes and were instructed in Jewish culture and religion.

[10]Lotte Kaliski, founder of the (private) Kaliski school in Berlin, noted: “Most of us came from very assimilated families and so did the children, but we understood that in order to give children a more positive attitude, they had to know something about their background” (quoted in Marion Kaplan, ‘The School Lives of Jewish Children and Youth in the Third Reich,’ in Jewish History, Vol 11, No. 2 (1997), pp. 41–52, p. 47. For further details regarding the Kaliski school, see Hertha Luise, Busemann; Michael Daxner, and Werner Foelling. Insel der Geborgenheit Die Private Waldschule Kaliski Berlin 1932 bis 1939 (Stuttgart; Weimar:Verlag J. B. Metzler, 1992) and Werner Foelling, Zwischen deutscher und juedischer Identitaet Eine juedische Reformschule in Berlin zwischen 1932 und 1939 (Opladen: Leske & Budrich, 1995).

[11]The Jawne Gymnasium and ORT teenagers were transferred en bloc to Britain in the late 1930s with their schools. As part of my doctorate I have been researching the lives these teenagers constructed for themselves once in Britain, comparing them with other refugees who came to Britain by other means, with their parents, or as adults already established in a profession.

It was decided to research and compare the Jawne and ORT schools for a number of reasons:

- 1. Find out to what extent the academic training the children received at the Jawne, and to what extent a practical training given at the ORT, would influence career choice.

- 2. Research the two schools as they are of historic interest due to being the only two schools that arranged for the transportation of their pupils to Britain as late as 1938 and 1939, as a school or in classes, as was the case with the Jawne.

Fifty six persons were interviewed: 36 men, 20 women – 18 Jawne pupils (including one teacher); 12 ORT pupils (including one teacher); 26 other persons: 15 who came over as youngsters and 11 as adults.

[12]The other four businessmen who helped Samuel Poliakov set up ORT were Baron Horace Gunzburg, Abram Zak, Leon Rosenthal and Meer Fridland. For further details of the foundings of ORT see Leon, Shapiro, The History of ORT A Jewish Movement For Social Change (New York: Schocken Books, 1980) chapters 1–10, regarding the founding fathers, pp. 11–38.

[13] Shapiro,The History of ORT: A Jewish Movement For Social Change, p. 174.

[14]Nele, Loew Beer, ’70 Jahre ORT in Deutschland Ein Rueckblick auf die Geschichte’ in ORT 1921–1991 70 Jahre ORT in Deutschland, 5 (Winter 1991/92), p. 45 . World ORT Union Historical Archives Geneva, From Despair to Hope:Rescue Actionof WOU of young Hitler-persecutedGerman Jews, state that at the end of July 1938 the school had 215 pupils; see Historical Archives, p. 18.

[15]World Ort Union Historical Archives Geneva, From Despair to Hope: Rescue Action of WOU of young Hitler-persecuted German Jews, p.17.

[16]World Ort Union Historical Archives Geneva, From Despair to Hope, p. 25 state, “The ORT Technical school in Berlin is at present (December 1st 1938), according to the unanimous opinion of all authoritative Jewish leaders in Germany, the best Jewish school, not only in Berlin, but in the whole country. It has a rich equipment which fills the two big floors of a factory building, and it possesses also a splendid staff of teachers and foremen collected with very great effort, after a long and extensive search, since it is exceedingly difficult at present to find in Germany highly qualified Jewish technicians and foremen. A number of first rate specialists in the field of factory organisation have become grouped round our Technical school. They devote it their time and energy giving it the benefit of their exceptional knowledge in an honorary capacity. I may mention among them:

- Professor Rupert, who was at the head of a State technical institute (Technikum) in Germany during 25 years;

- Regierungsrat Heiborn, who was an adviser of the State Patent Office during the last ten years before the present regime;

- Regierungsrat Landsberg, one of the chief engineers of the German railway administration;

- Civ. Eng. Wiener, one of the chief engineers of the General Electric Corporation in Germany (A.E.G.) – an outstanding specialist in the field of factory organisation;

- Civ. Eng. Feige, who was before an engineer of the Central Administration of the German Ministry of Posts, Telegraph and Telephone”.

[17]The hostel for the ORT school boys was located in Rosenthaler Strasse, in the east of Berlin, on the first floor of the department store ‘Wertheim’. The Reichsvertretung der Juden in Deutschland was in charge of the hostel and Herr Schoenfeld, a former band leader, was the manager.

[18]Helmut Gruenewald A Jew-Boy was not Allowed to be a German, Bristol, 1999. Unpublished family memoir, p. 43.

[19]On September 5, 1999 the Berlin ORT school boys ‘Class of 1939’ were reunited after sixty years at the British ORT Head Quarters in London. Max Abraham, aged 85, and his wife Hanni attended the function. Max is the only surviving teacher of that time. For further details see article written by Ruth Rothenberg, ‘Berlin “Class of 1939” is reunited,’ Jewish Chronicle, September 17, 1999, p. 20.

[20]Helmut Gruenewald, A Jew-Boy was not Allowed to be a German,Bristol, 1999, p. 48.

[21]Interview with Bernard Pomeranz. Personal Interview, taped. 10 December 1997. London. See also Berlin ORT School, boy’s diary written whilst in Kitchener camp in Kent: from September 1939 to November 1939.

[22] The ORT school boys were housed in five hostels – all in easy reach of the school. The main hostel, which also contained the dining room where all students assembled for meals, was situated at 226, Chapeltown Road; see Leeds ORT school prospectus, ‘From Despair to Hope: A Constructive Form of Help.’ The ORT Technical Engineering School, Roseville Avenue, Roseville Road, Leeds, p. 7.

[23]The Leeds ORT Technical Engineering School prospectus, p. 11.

– Talk given at ORT headquarters, Camden Town, London, UK, 18 July 2010 by Monica Lowenberg

Information reproduced here with the kind permission of Monica Lowenberg, for her father Ernst. All rights retained by Monica Lowenberg