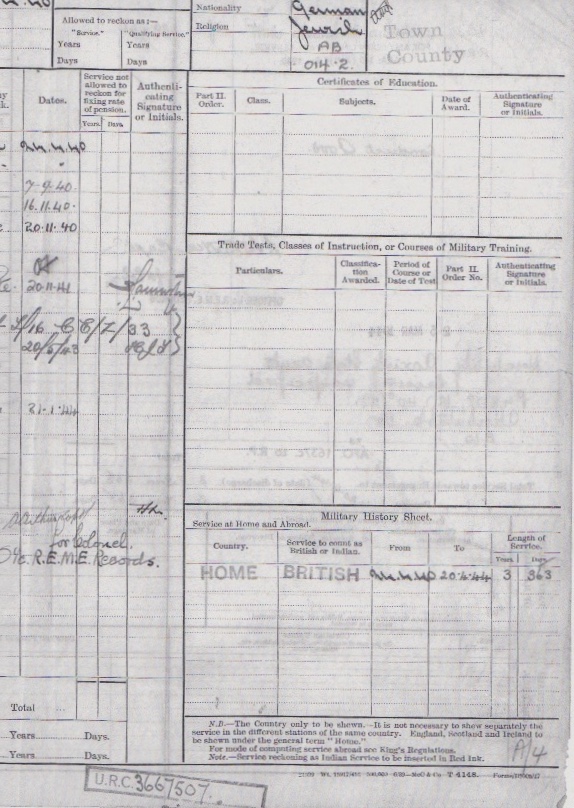

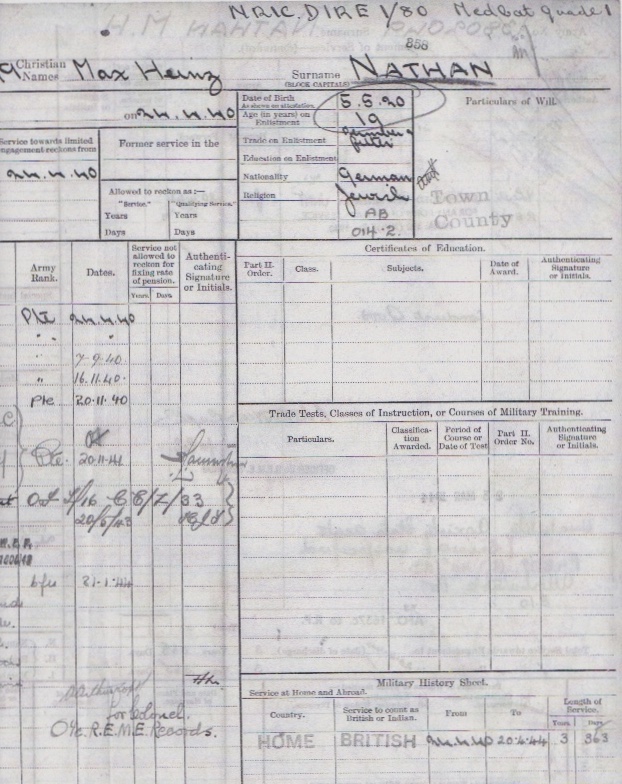

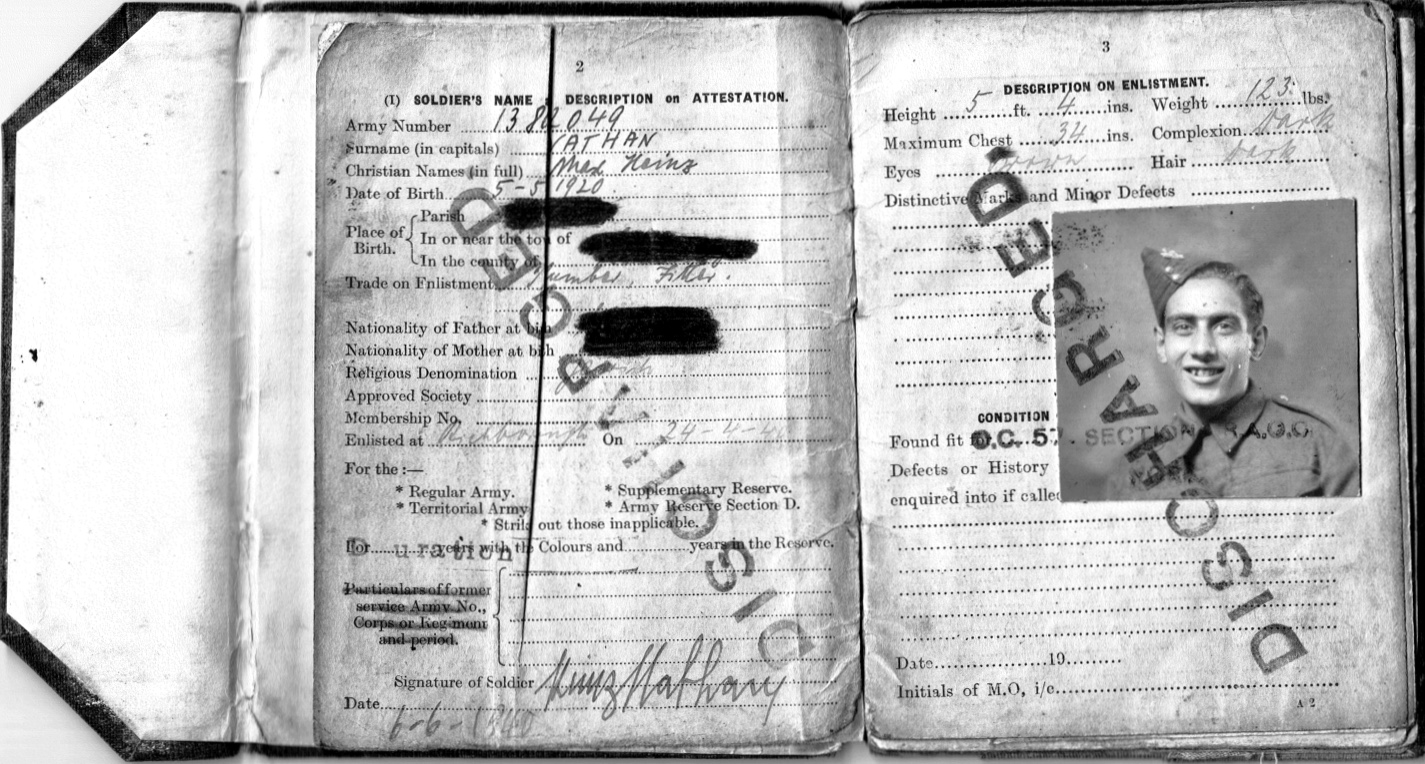

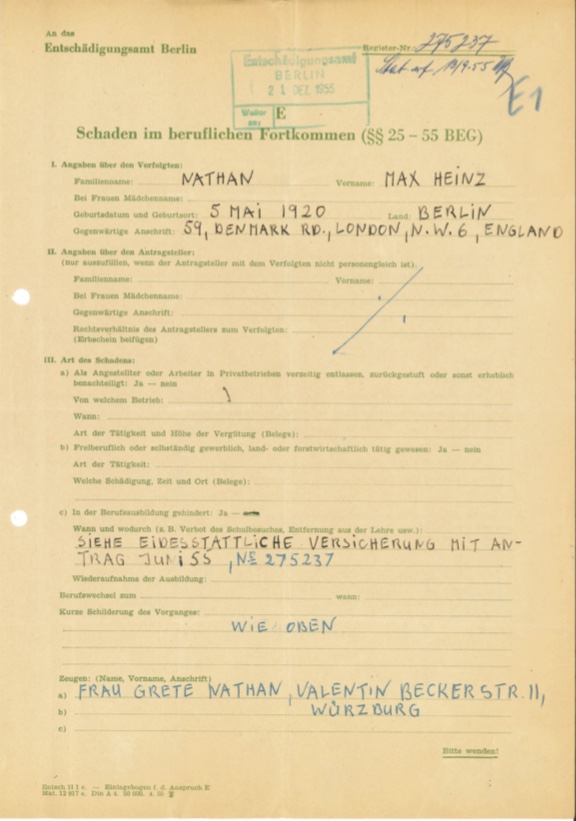

Born: Berlin, Germany, 5 May 1920

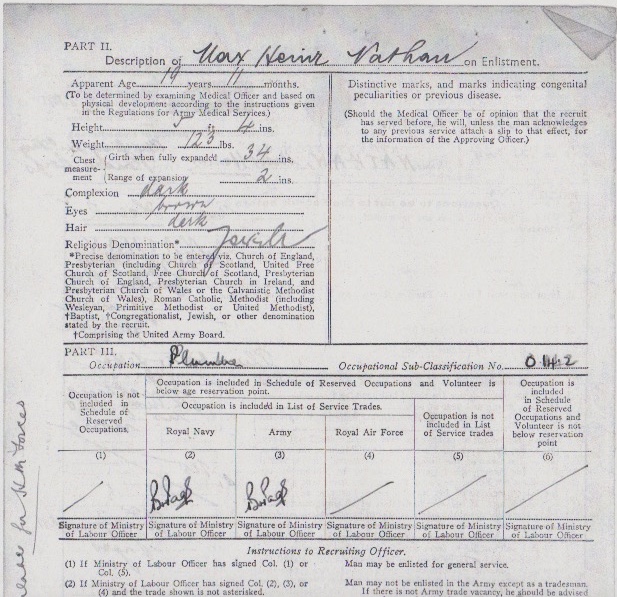

Occupation in country of origin: Plumber and pipe layer

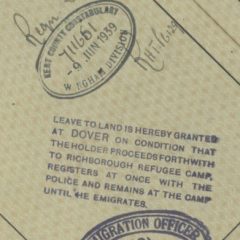

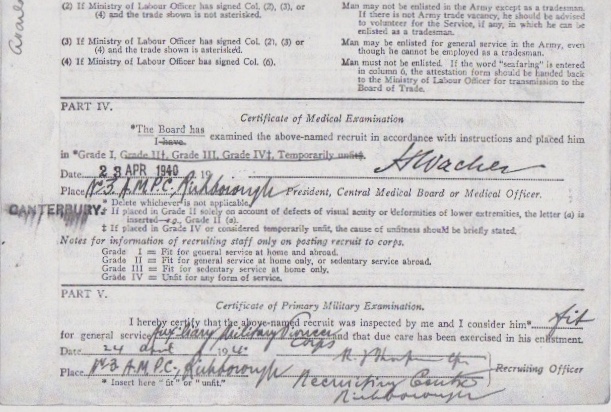

Arrived in Britain as a refugee from Germany on 9 March 1939

Documents

Male enemy alien - Exemption from internment - Refugee

Surname: Nathan

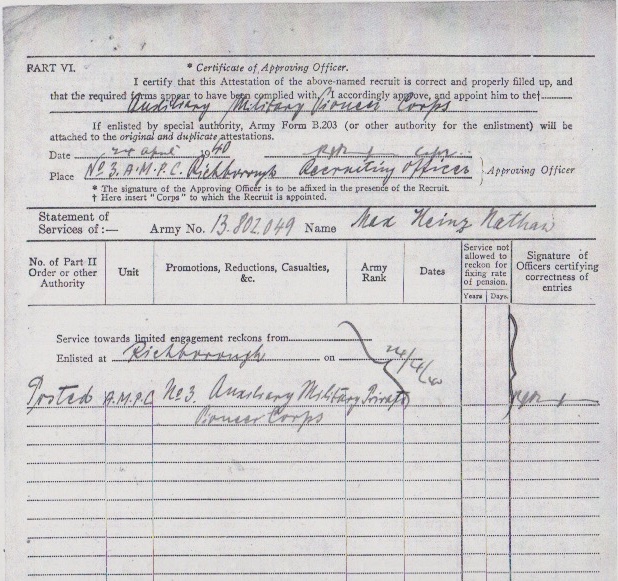

Forename: Max Heinz

Alias: -

Date and place of birth: 05/05/1920 in Berlin

Nationality: German

Police Regn. Cert. No.: 710 205

Home Office ref: C 504

Address: Kitchener camp, Richborough, Sandwich, Kent

Normal occupation: Plumber

Present occupation: Plumber

[Hand-written additions: A/2/07 O/C/8]

Name and address of employer: -

Decision of tribunal: Exempted "C" & 9a

Date 04.10.1939

Whether exempted from Article 6(A): Yes

Whether desires to be repatriated: No

Tribunal District: Richborough Camp Tribunal 1

To view the following images, please click to open in enlarged full form

To view the following image, please click to open in enlarged full form

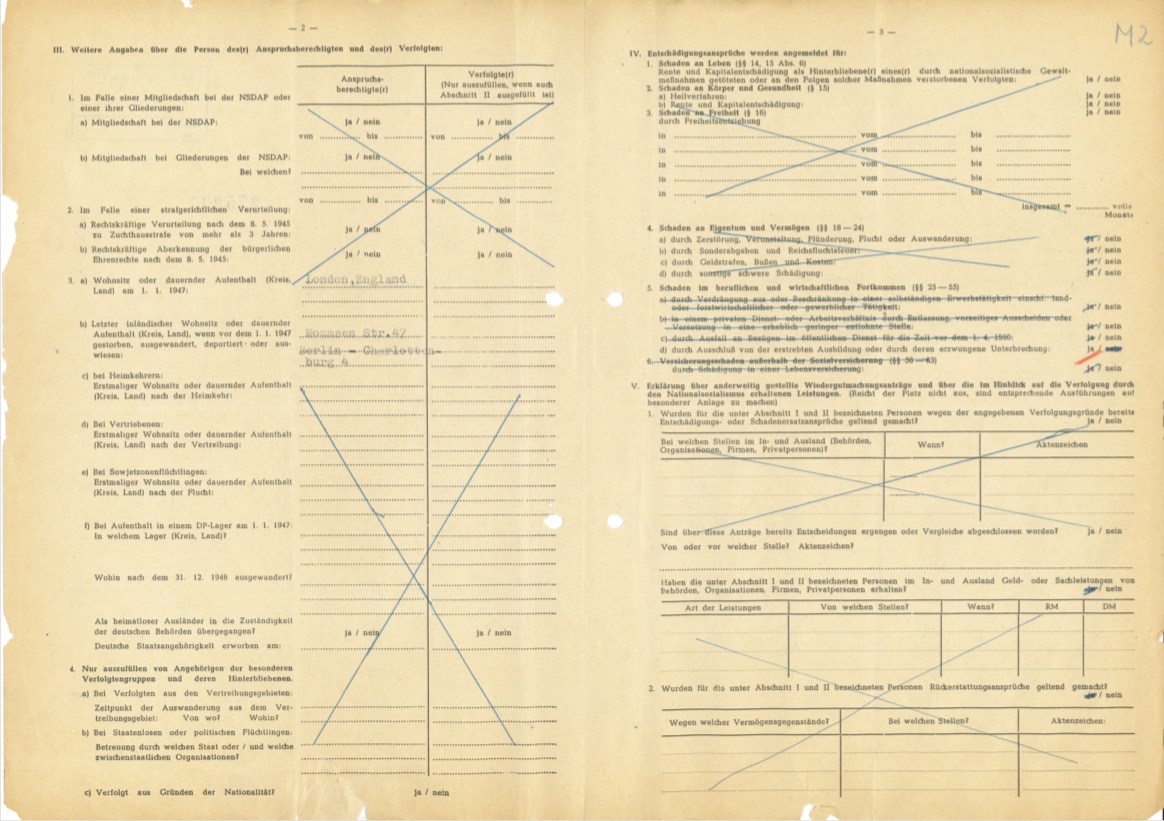

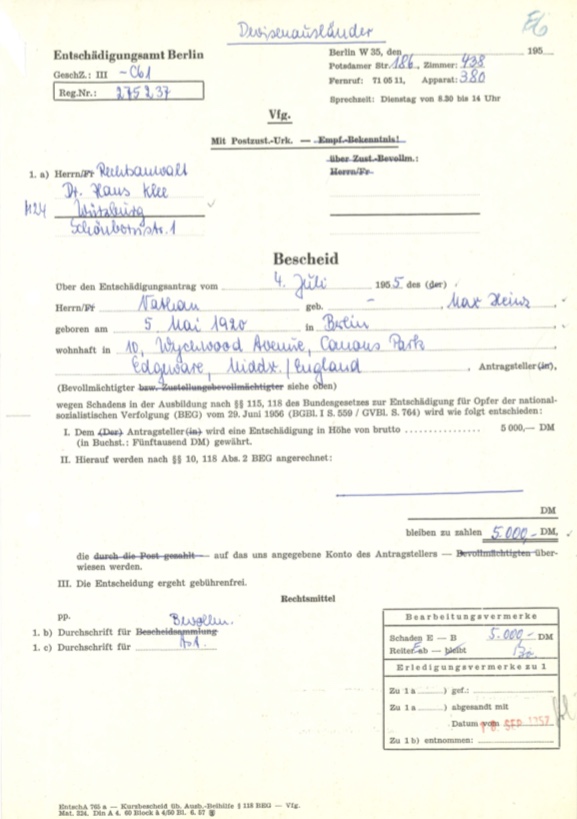

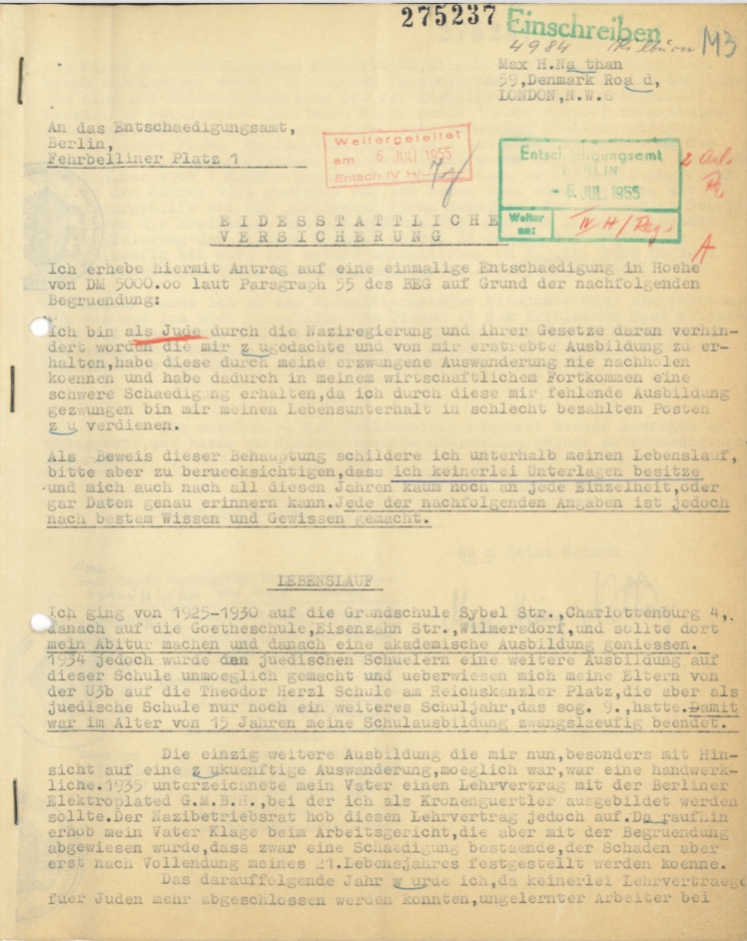

A family friend kindly translated the above text as follows:

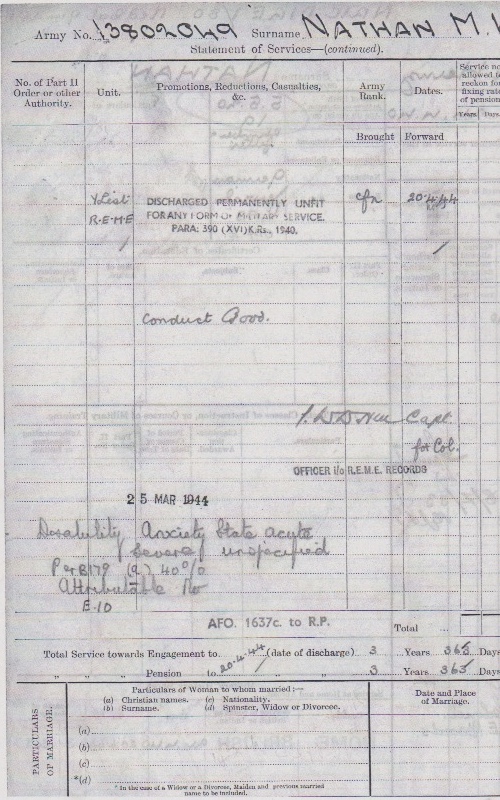

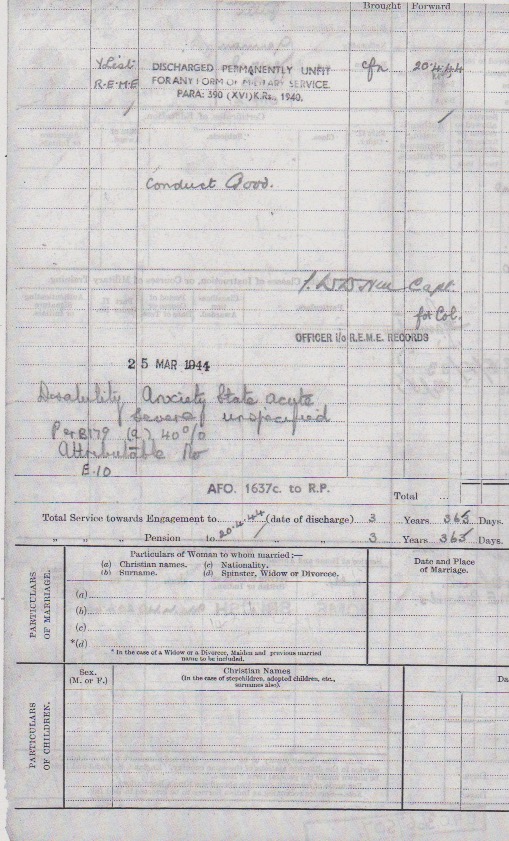

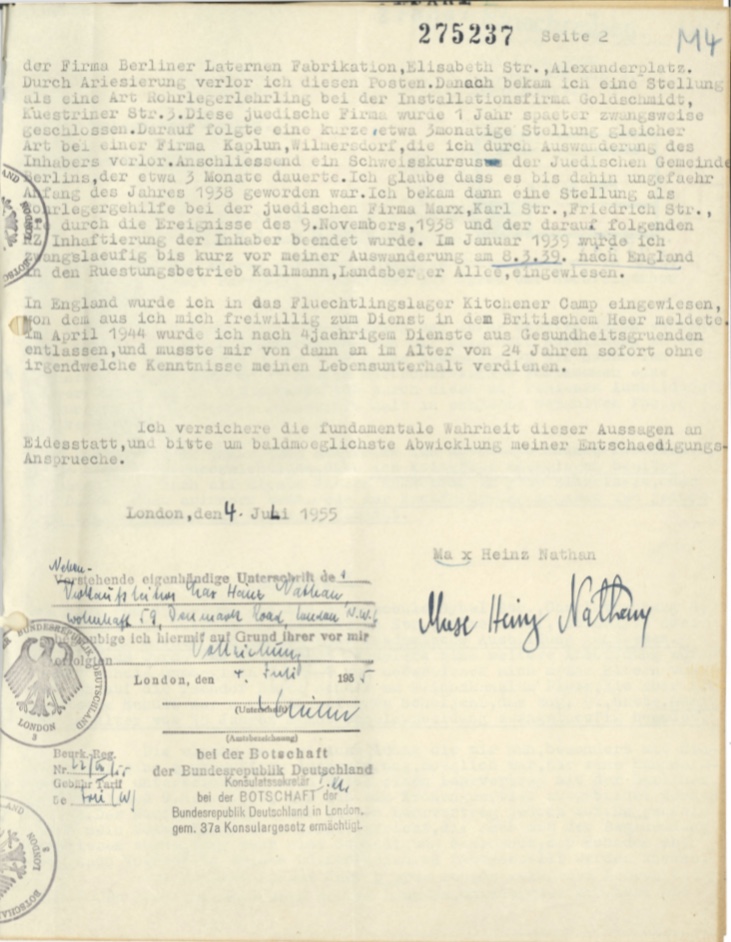

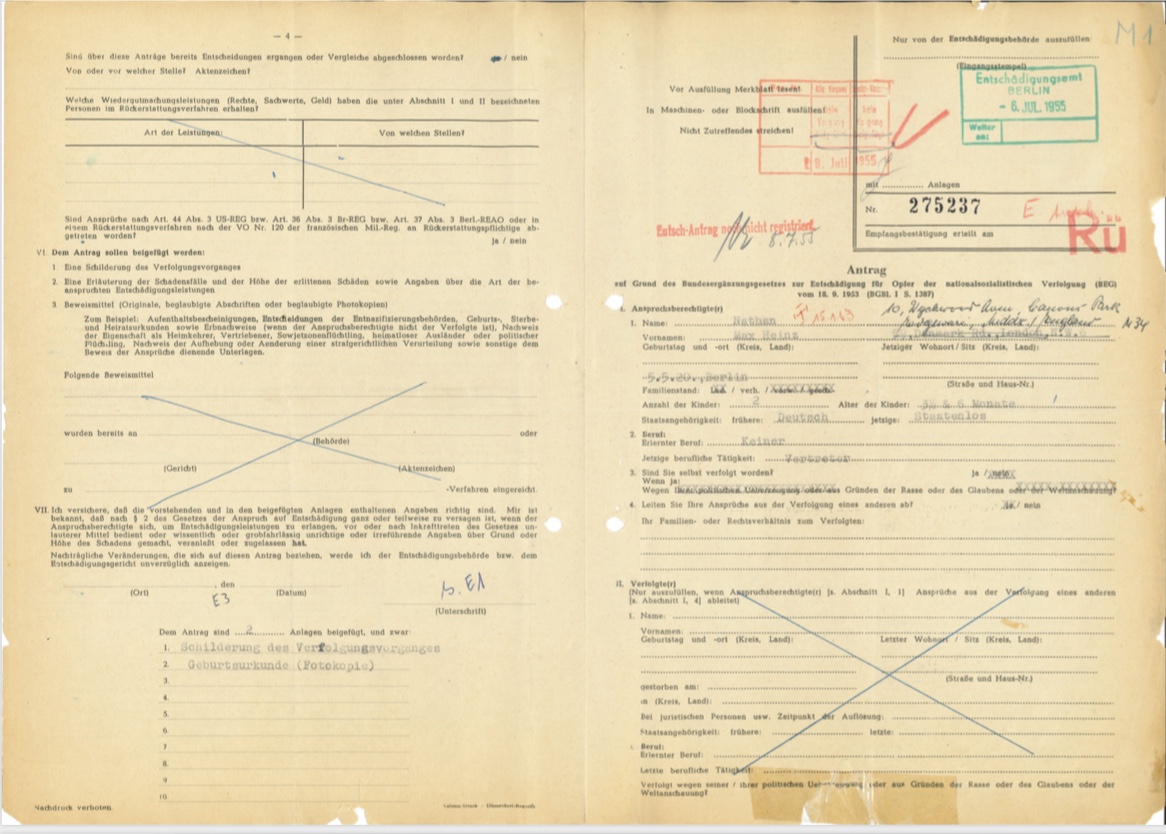

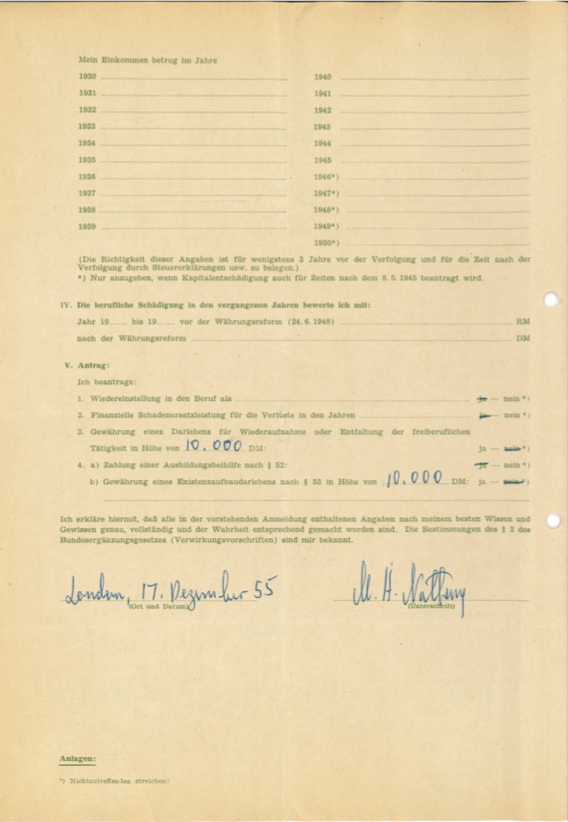

Herewith I apply for a one-time reparation in the amount of DM 5000 according to paragraph 55 of the BEG for the following reasons: As Jew I was prevented by the Nazi government and its laws from obtaining the education planned for me, and toward which I was striving, have, because of my forced emigration never been able to catch up, and have thereby suffered severe damage to my economic progress, as because of my lack of education I have been forced to work in badly paid positions. As proof of these assertions, I will describe the course of my life, please, however, be aware that I have no documentation at all, and that after all these years, I cannot remember every detail or even dates. All of the following information is nonetheless made with the best knowledge and conscience. LIFE From 1925–30 I attended the Grundschule Sybel Str. Charlottenburg 5. Thereafter the Goetheschule, Eisenzahn Str., Wilmersdorf, and was to make my Abitur there and after that enjoy an academic education. However in 1934 it was made impossible for Jewish students to be educated at this school, and my parents transferred me, from U3b [that’s a designation for a class level] on to the Theodor Herzl Schule at Reichskanzler Platz, which, however, as a Jewish school only offered one more year of education, the so-called ninth. With that, my education was forcefully ended at age 15. The only further training, which was now possible to me, particularly with respect to my future emigration, was a manual craft. [In] 1935 my father signed an apprentice contract with the Berliner Electroplated GMBH, according to which I was to be trained as Kronenguertler [an obsolete specialized trade for which the family has been unable to find an explanation] The (Nazibetriebsrat) Nazi Employment Council, however, invalidated this contract. Thereupon my father submitted a complaint to the Arbeitsgericht [Employment Court], which was declined with the reasoning that although damages had been incurred, the damage could only be assessed after I had my 21stbirthday. The following year, I became, because no training contract was possible for Jews anymore, an unskilled laborer at the firm Berliner Laternen Fabrikation [Berlin Lantern Fabrication], Elisabeth Str. Alexanderplats. I lost this job due to aryanization. After that I got a job as a sort of pipe laying apprentice with the Installationsfirma Goldschmidt [Installation Firm G], Kuestriner Str. 3. This Jewish firm was forced to close one year later. Thereafter followed a short, possibly 3 months’, position of the same sort with a firm Kaplun, Wilmersdorf, which I lost through the owner’s emigration. This was followed by a welding course from the Jewish Community Berlin, which lasted about 3 months. I think that by now it was early in the year 1938. I then got a position as pipe laying assistant at the Jewish firm Marx, Karl Str., Friedrich St., which ended because of the events of 9 November 1938, and the immediately subsequent arrest of the owner. In January 1939 I was forced to work at the Armaments Firm Kallmann, Landsberger Allee, until shortly before my emigration to England on 8 March 1939. In England I was assigned to the refugee camp Kitchener Camp, from which I volunteered for service in the British Army. In April 1944, after 4 years’ service, I was discharged for reasons of health, and had to start earning my living at age 24 without any skills whatsoever. I attest to the fundamental truth of this deposition under oath, and request a speedy disposition of my reparations application. [The stamp on the lower left is a notary stamp of the German Embassy in London, saying they watched him sign - the usual administrivia in such cases]

Memories

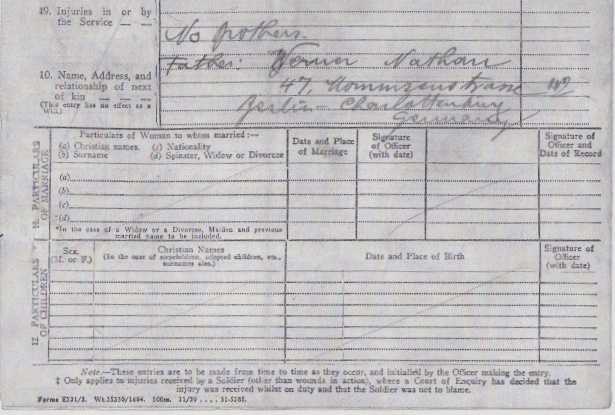

Max Heinz Nathan was born on May 5, 1920 in Berlin. He was the only child of Werner and Grete Nathan, who were also born in Berlin, like their parents before them. In fact the Nathan family history in Berlin dates back to 1671, when Max’s 6th great-grandfather, Nathan Veitel Meyer, was one of 50 families allowed to settle in Berlin, after the Jews were expelled from Vienna.

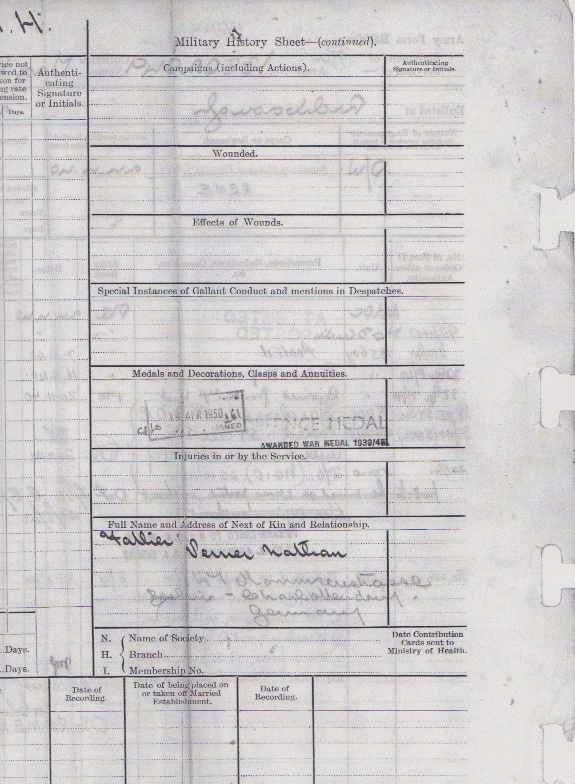

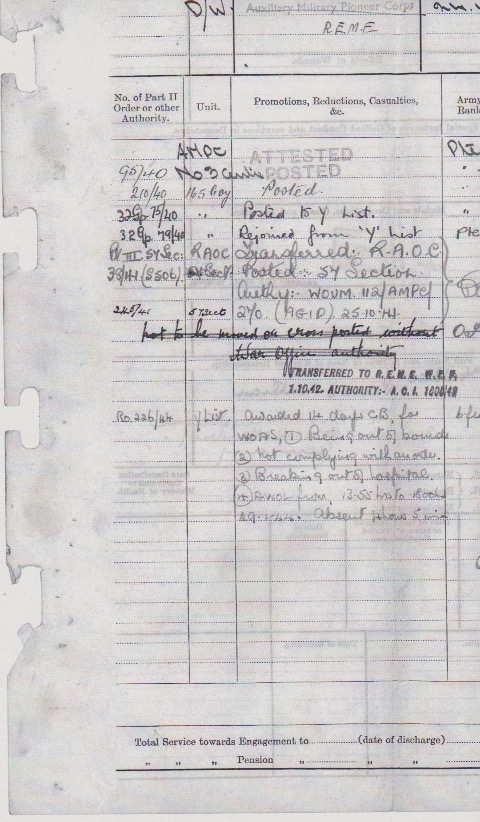

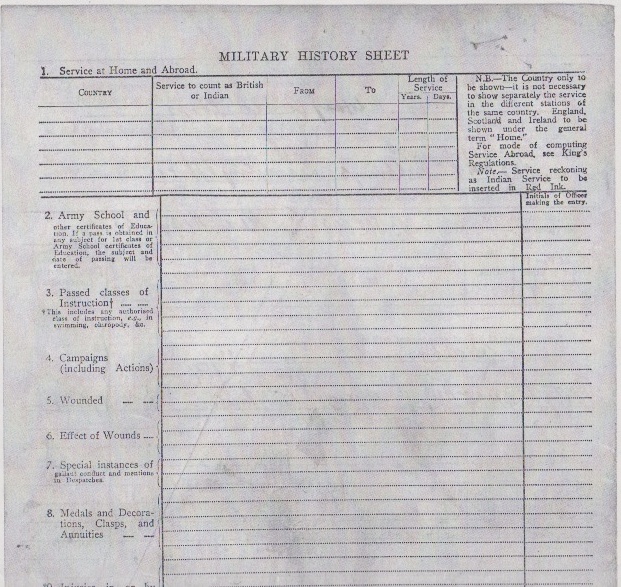

Max’s father Werner was a Rechtsberater, a legal adviser. The family was well off. But things really started to go downhill in 1931 for Werner, as he could no longer work as a Jew. And later, as a Jewish child, Max Heinz Nathan could no longer attend public school, and so he went to the Jewish ORT school in Charlottenburg, that had been set up to train Jewish boys in vocational skills – skills that would ultimately save Max’s life – plumbing, pipe laying, and engineering. This was the last school the Nazis closed down. Max’s parents had to sell everything they had bit by bit, just to survive, but they were determined to protect their only child, even if it meant they would never see him again. So in March 1939 Max was able to escape to England, and was immediately sent to Kitchener camp in Richborough, Kent. He was just 18 and was one of a group of 100 men who had the necessary construction skills to refurbish this old WWI refugee camp, which would soon house about 4,000 German Jewish men. Max dug trenches all day long, and laid water and sewer pipes. Once the bombing started, these Jewish men were finally allowed to form their own fighting unit in Britain, called the Pioneer Corps, and Max served for 4 years in this unit, the RAOC and the REME. The REME made him sit an entrance exam, since Max said he knew engineering. He passed it with 100%. They thought he had somehow cheated, because nobody had ever got 100% before! So Max offered to sit the exam again. And again he got 100%! During all of this time, he had no idea what was happening to his parents and grandmother back in Germany.

In November Werner and Grete were forced to move into a Judenhaus with Max’s grandmother Julie, as Jews could no longer rent from Aryans. Werner was working at the Jewish Community where he earned a few marks. It was while he was at work that Werner learned, two weeks later, that he, Grete and Julie were about to be deported to Theresienstadt concentration camp. He telephoned Grete and told her she needed to pack 3 small suitcases of clothes, and to hide his father’s stamp collection in amongst the clothes, to be used for bribes, if needed. And this was no ordinary stamp collection, as it consisted of first edition stamps. Of course they never saw their suitcases again once they were loaded into the cattle truck en route to Theresienstadt, or the stamp collection. Julie died of pneumonia and starvation 9 months later. She was 71. But Werner and Grete, somehow managed to survive – barely. The story goes that their Nazi guard gave them a slice of bread to eat every day, out of respect for Werner’s service to the Kaiser during WWI, and the lung injury he had received.

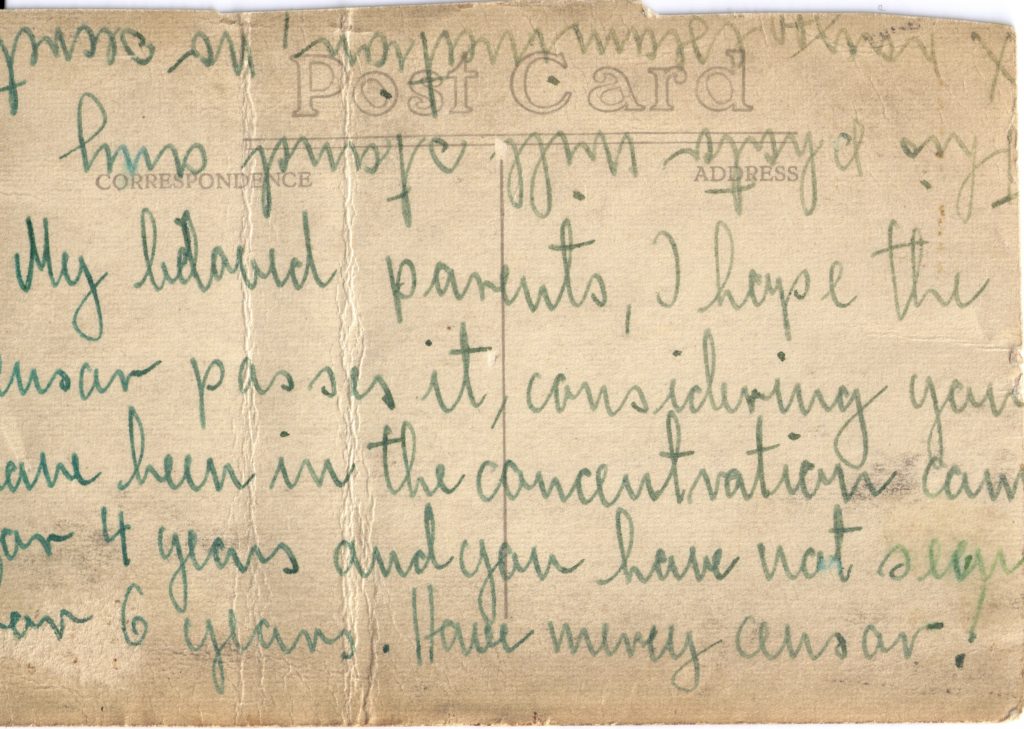

6 years after he had left for England, Max found out that his parents had survived Theresienstadt, and were now living at Deggendorf displacement camp in Bavaria. He sent them a photo postcard of himself in uniform, and on the back he wrote: “My beloved parents, I hope the censor passes it, considering you have been in the concentration camp for 4 years and you have not seen me for 6 years. Have mercy censor! This photo will stand any xray examination. No secret.”

Max then managed to get himself discharged and enlist with the American forces in Bavaria in their intelligence division, so he could be near his parents, and help them try and get out of Germany. For two years they tried, but nobody would take them because of Werner’s weak heart and lung condition. Eventually they were placed in a home for survivors in Wurzburg. It was there, despite their ill health and all they had suffered, they were able to have some measure of peace and quiet in their final years. They were also able to meet their first granddaughter Judith, when she was just 2 years old. They are buried in the Jewish cemetery in Wurzburg.

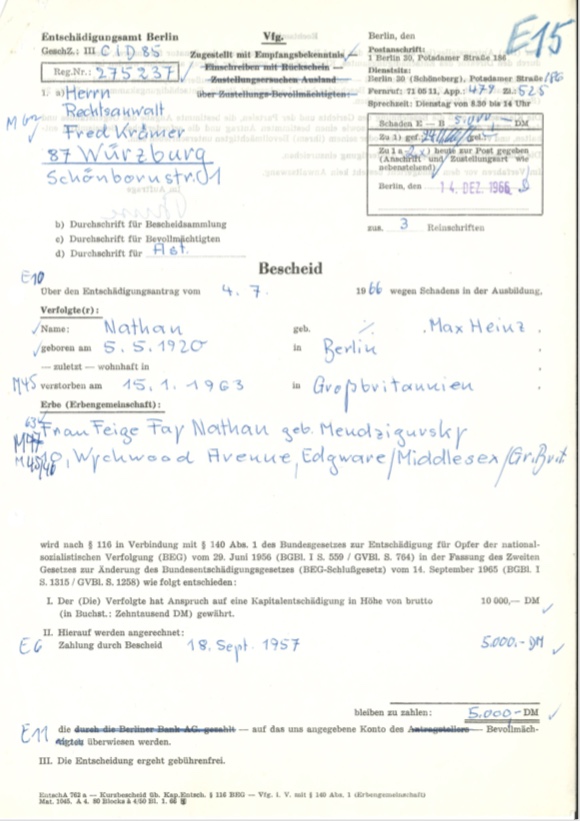

Max Heinz Nathan met his future wife Fay Mendzigursky at the Cosmo restaurant on Finchley Road around July 1948. The Cosmo had become a haven and a sanctuary of sorts for German-speaking refugees like Max and Fay, most of whom lived in N.W. London. Fay had escaped on the Kindertransport from Leipzig, Germany. They were married 3 months later in a registry office. When their first daughter Judith was born 3 years later, Max was unemployed, England was still on rations, and they lived in just one tiny room in a Maida Vale slum. But Max was very intelligent and learned things very quickly. He started to sell life insurance. Things got better and the family moved out to the suburbs (Edgware) and into their own home. But tragically, six years later, Max died unexpectedly of a heart attack in January 1963, while driving to work. He was just 42, Fay was 38, and their two daughters, Judith and Jacqueline, were just 11 and 8. Max is buried at Hoop Lane cemetery in Golders Green, London, just a few rows away from Leo Baeck, the famous Berlin rabbi.

Written by Judith E. Elam for her father, Max Heinz Nathan

Photographs

Translation to English

My beloved parents, I hope the censor passes it, considering you have been in the concentration camp for 4 years and you have not seen me for 6 years. Have mercy censor! This photo will stand any xray examination. No secret.

Submitted by Judith E. Elam for her father, Max Heinz Nathan