Born: Berlin, Germany, 8 December 1912

Profession in country of origin: Accountant

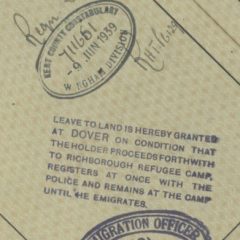

Arrived in Britain as a refugee from Germany, 23 August 1939

Documents

Male enemy alien - Exemption from internment - Refugee Surname: Grünbaum Forename: Moses Chaim Alias: - Date and place of birth: 08/12/1912 in Berlin Nationality: German Police Regn. Cert. No.: 767899 Home Office ref: C 3806 Address: Kitchener camp, Richborough, Sandwich, Kent Normal occupation: Butcher Present occupation: Road building in Camp Name and address of employer: - Decision of tribunal: Exempted "C" Date 20.10.1939 Whether exempted from Article 6(A): Yes Whether desires to be repatriated: No

Grünbaum, Moses Chaim Release auth cat 17 07.01.1942 Dunera Released on arrival per SS Themistocles 06.10.1942 08.12.1912 767899 Richborough E.C. G18052

Source: National Archives, Home Office: Aliens Department: Internees Index, 1939-1947.

Editor’s note: We are not allowed to reproduce National Archives (UK) images, but we are permitted to reproduce the material from them, as shown above.

Memories

The following PDF is a form of diary, or collection of reminiscences, about life in Kitchener camp, internment on the Isle of Man when war broke out, deportation on HMT Dunera, and the early weeks at Hay internment camp in Australia.

Below are the first few pages that address the focus of this project – Kitchener camp. However, we encourage you to read the remainder of these pages in the PDF, which form a remarkable and important account of British interment camps, the infamous Dunera voyage, and internment camps overseas.

This diary was written in German. One of Moshe’s daughters inherited it after her father’s death, and she had it translated by Benjamin Sklarz.

We are very grateful to the family for taking the time and trouble to organise these materials for the Kitchener project.

Diary of Moshe Chaim Grünbaum

Hay, 10th December 1940

This book is not to be a diary. Rather, I wish briefly to record here those experiences which I would like to recall in later years, irrespective of their being good or unpleasant.

I am starting these records with the day I left Germany, because that day marks the beginning of a new chapter in my life.

I left Germany on the 23rd August 1939, having already postponed my departure several times. Any further delay I considered to be pointless, since I foresaw clearly the imminent outbreak of war against Poland. I departed with a very heavy heart because I had to leave my beloved parents behind, for whom I had so far not been able to obtain an immigration permit to any country.

At that time, political events were overtaking each other at headlong speed. On the 22nd August 1939 the German newspapers were still announcing the pact between Germany and Russia. To this day, I see in my mind’s eye how the Berliners received the news. The papers sold out like hot rolls (to use a popular expression). Everybody was moved to smile and shrug their shoulders. But then, people knew that this business was aimed mainly against Poland. I hurried my departure for the further reason that two tenants in our house in Berlin had been called up, although they were part of an older draft group. When I arrived in Dover via Ostend on August 24th, Britain’s declaration of ‘mobilisation’ was being announced. At that moment I realised that I had left Germany in the nick of time.

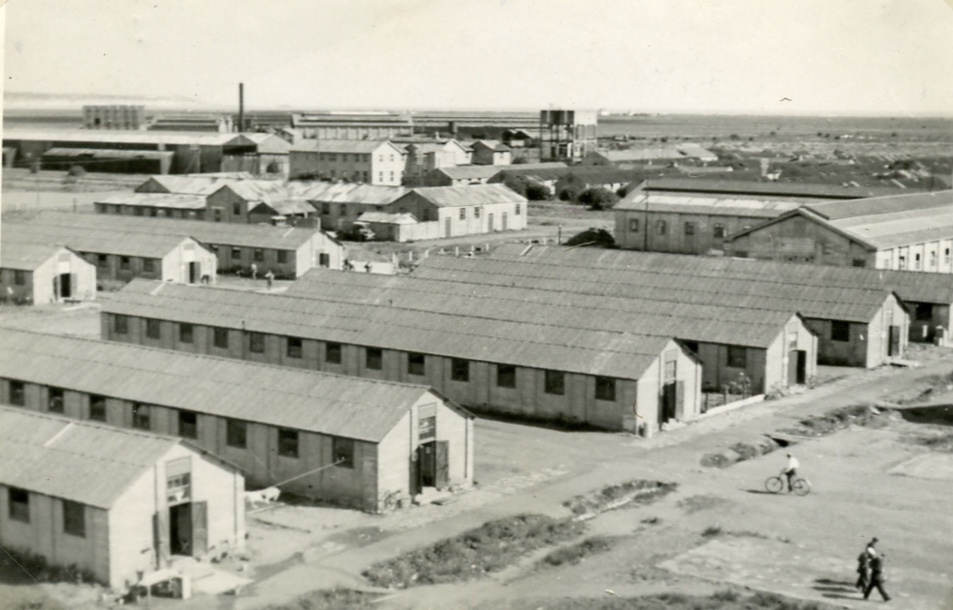

My destination was now ‘the Kitchener Camp’ (K.C.). This was a former World War I camp where General Kitchener had assembled soldiers for their shipment over the Channel to France. This camp, old and decayed as it was, was placed at the disposal of the ’Anglo-Jewish Committee for the Care of Refugees’ in accordance with a plan to establish a transit camp for Jews from Germany. I was the 3253rd man to head for transit via this camp. It lay on grounds near the small town of Sandwich. The condition of the huts was such that their four walls barely stood upright. It was now our task to set these huts to rights as far as possible. We had to install doors, windows, roofs, window panes, and electric lights and do all sorts of other jobs. After these repairs, each hut was divided into two sections, and 36 fellows were accommodated in each.

As life in the camp proceeded, everyone was assigned a job. Thus, workshops were set up for bricklayers, painters and carpenters, glaziers, electricians and locksmiths, all for work on the huts, while a road-building team was formed for road works. As the need arose, workshops were also created for shoemakers, tailors, barbers, bicycle repair, printing, watch-making, as well as precision engineering. All craftsmen were assigned to these groups, in which they had to work. Unskilled workers, and those from over-staffed sections, had to work in vital or other essential operations. Here the kitchen, where a lot of work was required, was the first to be considered. I will not go into all the other work departments, but I must outline the kitchen operation. One has to remember that 3,500 men were fed here daily, which was achieved by 400 men working in two shifts. I do not have the least intention of praising their efforts: on the contrary, this was the worst managed operation in the whole camp. An average 40 per cent of all the food was actually left uneaten, because what was prepared from the available ingredients was a disgrace.

I would like to add that the following facilities contributed to making camp life more agreeable: the cinema (with 400 seats), the canteen, a theatre group and an orchestra, a school, a sports ground, table-tennis, and so on.

It was on the 24th August 1939 that I arrived at the camp just described. Having formed some picture of the camp from previous descriptions, I was still somewhat disappointed. Nevertheless, I was glad to have left Germany, because it was apparent from the newspaper reports that the outbreak of war against Poland was only a matter of hours. War preparations in England had started in earnest during my first week there, and I too was conscripted. The K.C. was required to provide several work groups for filling sandbags in the neighbourhood. So this is how I experienced the beginning of the war: it was a Sunday, the 3rd September 1939. I was working with about 70 comrades in Eastry. We were filling earth, or rather, chalk, into smaller sacks, which were then piled up along the outer wall of a local hospital, in front of the windows.

Then, at 11 o’clock in the morning we heard the sirens and the ringing of bells, after the news at 10 o’clock, of the ultimatum to Germany to withdraw her troops from Poland. At the sound of the sirens, all of us, including the British guards, were quite startled and took shelter inside the hospital. Only then did we hear Chamberlain’s observations on the radio, describing all the negotiations, and finally ending with the words: “We are now at war with Germany.” This was also the prelude to changes in routine at the K.C. First of all, study classes were interrupted. People were upset, and as a result, the work details did not perform as usual. What was naturally worst of all was that all postal contact with our nearest and dearest was cut off.

That same month the Archbishop of Canterbury, Primate of all England, came to visit us. Among other things in his address, he said: “I am proud that this country has had the honour of being able to provide you with a place of refuge. I hope furthermore that this country will take advantage of all the help you are willing to give.” He ended by saying: “It will be a great achievement when we in this country will regard you not merely as refugees whom we were glad to welcome, but as fellow workers in a common cause that will unite us all.” People sighed with relief at these words. We thought that we would now be integrated into the British economy, because the Archbishop’s visit and his speech appeared in all the newspapers. We already saw ourselves living outside the camp, working as employees at a job, living once more in a town among other people and societies. But all these were just thoughts, dreams, and wishes.

Around the 20th October, Lord Reading appeared at K.C. and urged people to join the H.M.P.C. (His Majesty’s Pioneer Corps). Although the nature of the H.M.P.C. was not made clear in Lord Reading’s first address, it emerged clearly from his discussions with the hut leaders. The agitation among our fellows can well be imagined. Some had left a wife and family in Germany, others, parents and siblings – and now they were to fight against Germany. They dared not think or imagine what would happen to their relations if they themselves were to fall into enemy hands. The following also has to be taken into account: the majority in K.C. were migrants, people who, sooner or later, intended to emigrate to the U.S.A., South America, Palestine, or elsewhere. The wives and children of some had already reached these destinations. It is thus more than understandable that most of these people refused to join the H.M.P.C. I do not wish to enlarge on several anxious days that we experienced, nor on the pressure which, so to speak, the Jewish Committees exerted on us in order to make us join, because those incidents were more than mean.

Around January 1940 the H.M.P.C. made a start in the K.C. Out of some 1,850 men who had originally reported, finally only about 1,000 remained. The other residents of the K.C., who originally numbered 3,500, resolved into those who wanted to migrate and those who, though without migration plans, did not join up. The H.M.P.C. was, as it were, accommodated among us. The non- joiners moved into the hindermost huts, vacating some 15 huts in front. Those who joined up were sworn in, given uniforms and assigned to these military huts. For every man accommodated in the K.C., the army now paid about 2s. 2d. a day. Out of this income, the K.C. Committee was able to increase our wages, or rather, our pocket money. This was paid out only to those who worked, and, in the first two months of my time there, had comprised a weekly 6d. + 21⁄2d. in the form of a postage stamp for one letter abroad. This pocket money was then raised to 1s., 1.6s., and 2.6s. until, finally, payment continued at 5s., or 6 to 7s. for a “foreman”. I myself, having been assigned to the shoemaking workshop as a foreman through my connections, received a weekly 6 s. according to the new pay scheme. Of course, I held only the business management, but did acquire some shoemaking know-how during those seven months, so that in the last two months I was additionally given the management of the workshop. Now and again I would try and earn something on the side. Possibilities for this existed in the K.C. as follows. The army authorities were setting up a radio station on a site opposite the camp. It was to be a service that would listen in to all German broadcasters. A secret project, this station was guarded day and night. Guard duty was continuous, and carried out in four shifts which relieved each other. Now it happened that one or other of the guards fell sick. For lack of manpower, his replacement would have to be found in one of the work groups. So I too would occasionally report for the night-shift, from 12 o’clock midnight to 6 o’clock in the morning, and thereby earned 10d. per night. The work required me to sit in front of a radio receiver and listen in on the Deutschland transmitter, or Breslau, Hamburg, and also Warsaw. I had to wear a headset the whole time and to report everything I heard. This was done every fifteen minutes on a pre-printed form. When music was broadcast, I had to indicate every piece by name, give the name of the composer, and for how many minutes the piece was played, along with other data. News of the day broadcast in German, English, and French, or anything beyond the programme, special announcements, etc., had to be “recorded”. The recording equipment stood in another room and every receiver was connected to switches. For example, when I heard a special announcement, I would simply switch over to have it recorded by that recording device. When the announcement was finished I had merely to disconnect the recorder and note down that the item had been recorded. Between 2 and 5 o’clock in the morning there was usually total silence and I used those hours to deal with my letters.

Submitted by Judy Sherwood, for her father, Moshe Chaim Grünbaum

The second of Moshe’s diaries may be found at the link below

The final instalment of Moshe’s thoughts and diaries may be found in the following PDF document

Photographs

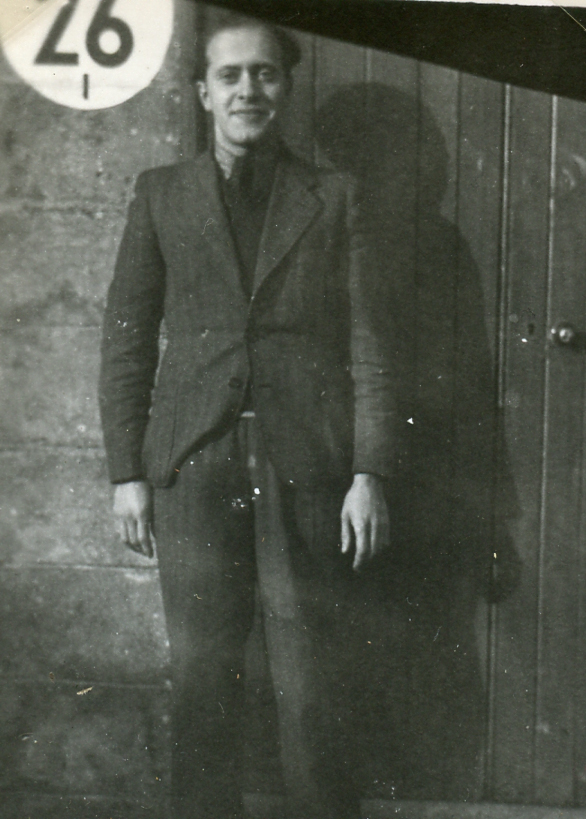

Hut 26/I

Photographs submitted by Judy Sherwood, for her father, Moshe Chaim Gruenbaum.