With the kind permission of Allen Sternstein

Source: Alan E. Steinweis Kristallnacht 1938. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2009; pp. 1, 57, 61, 107.

‘Kristallnacht’

Kristallnacht – the Night of the Broken Glass: this is the name given by the National Socialists to events with which many are vaguely familiar from school history lessons. The origins of the term are disputed and controversial, however, and more recently it has been less used because its focus was and remains on the destruction of property. The more recent use of pogrom or terror places the emphasis on attacks on people primarily, and on property as a secondary characteristic. Even this seems problematic for various reasons, nevertheless, and so we stay with ‘the events of November 1938’.

The chronology of these events is complicated, but they are generally deemed to have begun in public, at least, on Monday, 7 November 1938, when Jewish teenager, Herschel Grynszpan, shot a Paris-based German diplomat, Ernst von Rath (https://www.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%206321.pdf and in PDF form: Yad Vashem Shoah Resource Centre).

This shooting was used as an excuse to unleash a horrific series of attacks against German and Austrian Jews.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herschel_Grynszpan

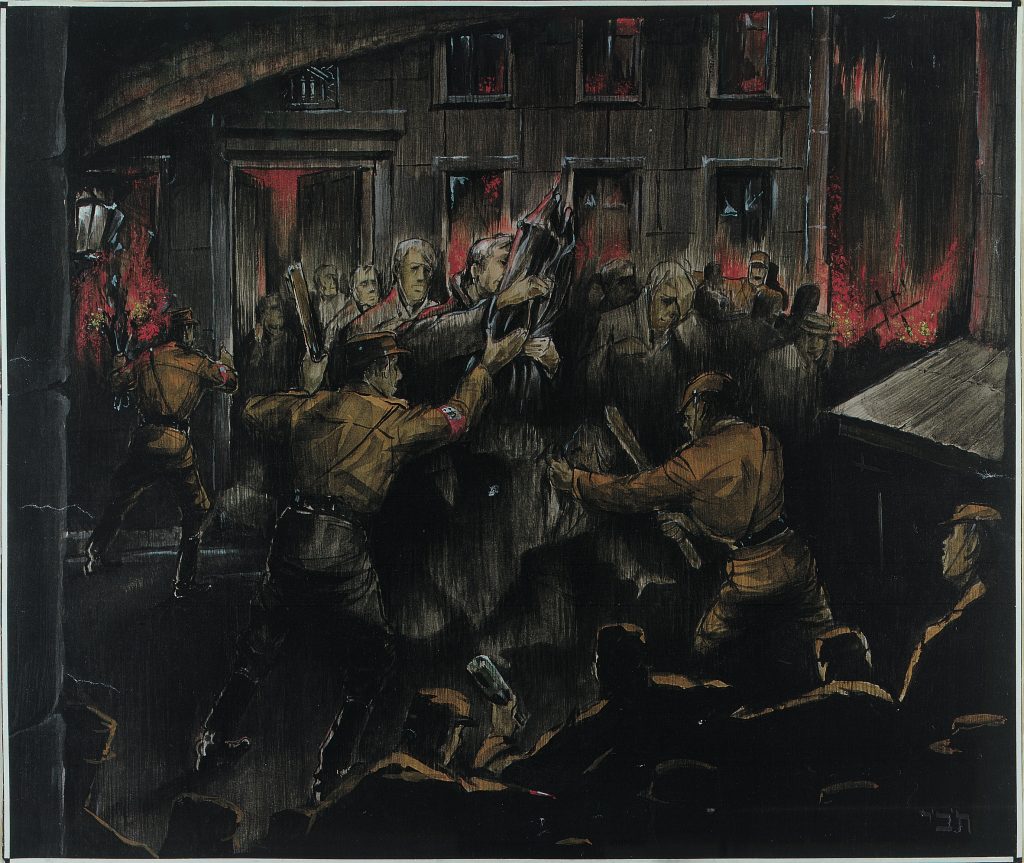

By the end of the day, organised anti-Jewish riots had been deliberately started in several towns and cities across Germany, which were expanded upon during the following few days.

Source: Steinweis 2009

Frankfurt am Main

As an example, in 1938 in Frankfurt am Main, there was a Jewish population of around 35,000. There were three synagogues, the school, and many other Jewish cultural and social organisations, including a museum sponsored by the Rothschild family. As Jews had been ostracised and legislated against for many years by this stage, at least since 1933, the majority had extended their links to others facing the same prejudices. Coupled with this, German authorities had gradually been drawing up lists of Jewish people and properties, so the act of locating them quickly during those November days was not difficult.

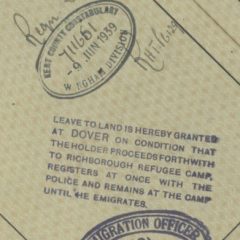

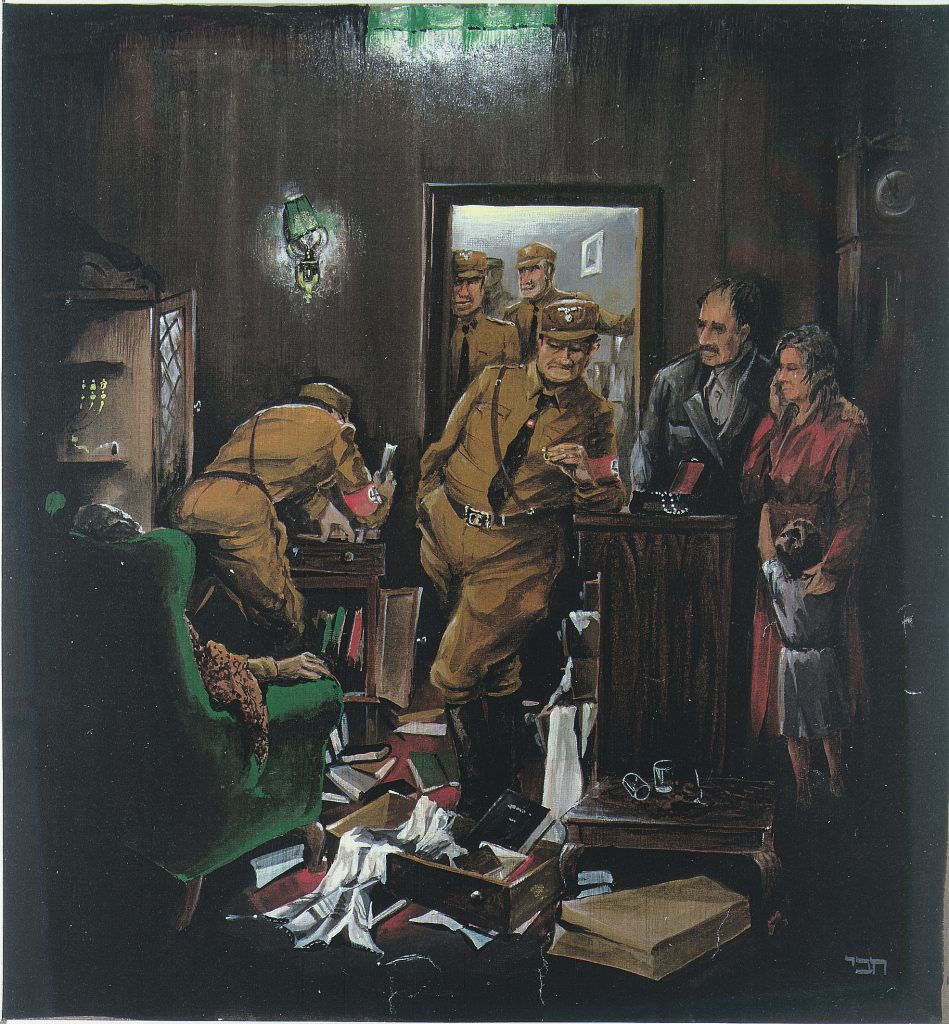

The Frankfurt pogrom started with a fire that was set in one of the synagogues at around 5am on 10 November. Young boys were forced to cut up the Torah scrolls and to burn them. By around 6.30am, a majority of Jewish homes were being invaded by squads of between five and ten men. Many hundreds of Jews sought help over this time in the offices of British Consul General Robert T. Smallbones, who ignored orders not to intervene. He was in constant touch with people, trying to obtain emigration permits for Palestine and the UK.

Source: Thalmann and Feinermann, Crystal night: 9-10 November, 1938. London: Thames & Hudson, 1974

With the kind permission of Allen Sternstein

By midday on 10 November, “There was not a single Jewish shop which had not been ‘completely demolished and wrecked inside and out’ … Several Jewish-owned cafes and a hotel had also been destroyed … Meanwhile gangs of thugs marched through the streets shouting ‘Perish the Jews!’ And ‘Beat the Jews to death!’” Sections of the city where poorer Jewish people lived were attacked first, with Consul Smallbones noting “scenes of indescribably destructive sadism and brutality” (see http://www.ajr.org.uk/index.cfm/section.journal/issue.Jun13/article=12732 and in PDF form: Smallbones_The Association of Jewish Refugees).

Source: Read and Fisher, Kristallnacht: Unleashing the holocaust, London: Michael Joseph, 1989; p. 102/3

With the kind permission of Allen Sternstein

By evening, the arrests had begun, with Jewish men being rounded up and confined: “A large crowd had gathered outside, screaming insults and abuse at each convoy as it arrived. Inside … Jews were stripped of all personal possessions, including money, and held through the night and next day without food or water”.

Source: Read and Fisher 1989

“The camps had been set up to ‘silence by terror’”

Source: Thalmann and Feinermann 1974, p. 117

Thousands of people had long journeys to the camps and many of the methods that were to be seen in wartime concentration camp journeys and in the camps themselves were established here and now.

Those transported from Breslau, for example, had a “ten-hour journey to Buchenwald, during which they were viciously abused by SS guards” (Stenweis 2009; p. 98).

As another example, until early autumn 1938, Dachau had housed around 2,000 people; in late September, most were transferred to Buchenwald. Between 10 and 16 November, around 11,000 Jewish men arrived. The camp was simply not prepared for accommodating this number of people, despite having been extended during the later years of the 1930s. Many new arrivals had to sleep outside, in freezing November temperatures. There was little food or water, and few latrines or showers (Steinweis 2009; p. 109).

Arrival at the camps was traumatic for all, but in order to survive people had to adapt quickly. Detainees were received under harsh spotlights, “by ranks of hundreds of armed and helmeted SS troopers … They were kept standing without food or water for eight hours while they underwent admission formalities. Their heads were shorn and they passed through alternately icy and scalding showers (Thalmann and Feinermann 1974; p. 118). The men had to run a gauntlet of SS, “while being kicked and beaten … accompanied by a great deal of verbal abuse and humiliation” (Steinweis 2009; p. 109).

Hundreds died between 1938 and early 1939, many at the hands of SS guards; quite a number killed themselves on the electric fencing – also a sign of things to come. Many deaths also resulted from heart attacks and from other medical problems – there was no insulin for diabetics, for example, and proper medical attention generally was not made available (Steinweis 2009; p. 112).

“According to the most modest estimates, based on documents at the Wiener Library, the pogrom claimed the lives of between 2,000 and 2,500 men, women and children, and permanently affected all the others who survived its horror” (Thalmann and Feinermann 1974; p. 118).

—————————-