The Central British Fund for German Jewry was founded in Britain in early 1933 in response to the National Socialist Party taking power in Germany. The CBF founders included Otto Schiff (a German Jew who had emigrated to Britain in 1896 and who had long been involved in helping Jewish refugees), Leonard G. Montefiore (who had been president of the Anglo-Jewish Association and was then a co-chair of the Joint Foreign Committee), Simon Marks (Chair and MD of Marks & Spencer), Robert Waley Cohen (MD of Shell), Lionel and Anthony de Rothschild (partners in N M Rothschild), and Chaim Weizmann (who would later become Israel’s first president).

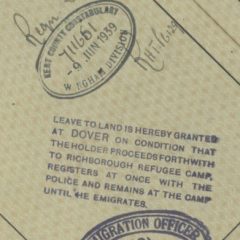

Throughout the 1930s, the CBF guaranteed to the British government that refugees from Nazi oppression would not become a burden on the public finances, and they undertook to raise the funds required to meet all costs and housing needs.

Although this is not always understood by the wider public, the CBF was responsible for organising and funding the Kindertransport, as well as for organising and funding the running of Kitchener camp in Kent.

With the kind permission of Allen Sternstein

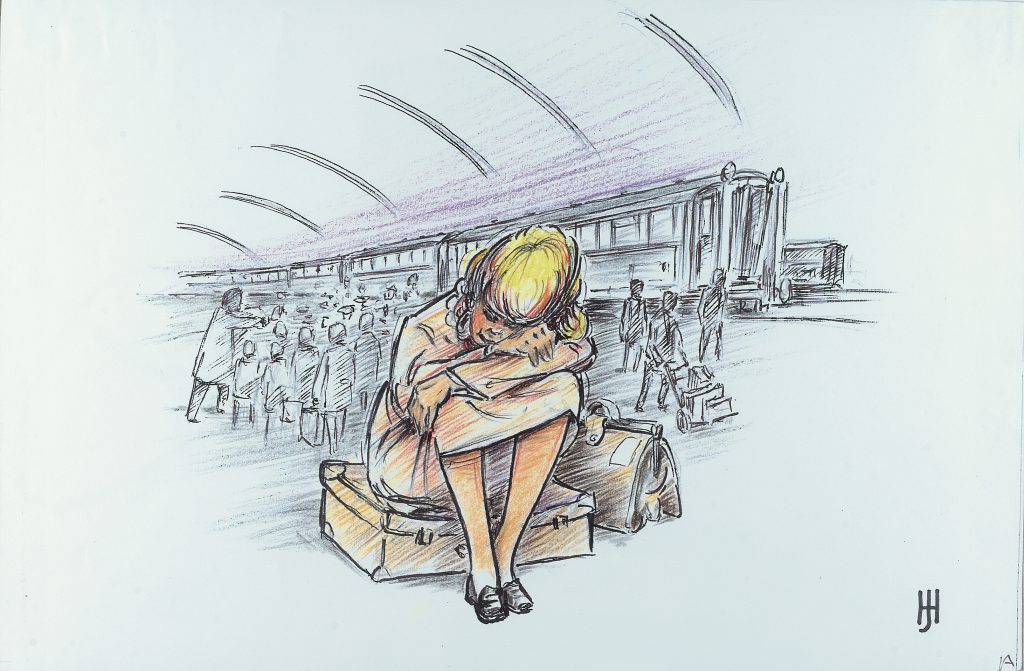

And whatever the arguments about these events – over what could have been achieved or what should have been done – at a simple human level, many of us owe these people a deep debt of gratitude.

Indeed, we owe them our lives.

———————————

The CBF managed to raise extraordinary levels of funding for German Jews, who were increasingly needing to find a safe way out. The CBF made a first appeal in the Jewish Chronicle in May 1933, raising £61,900; by the end of that year, almost £250,000 had been raised; and by the end of the following year another £176,000 had been raised, and these were not easy years for people, financially.

The CBF helped Jews to leave Germany in all kinds of ways, including scholars helping scholars, for example. In a movement headed by leading British and American physicists, some brilliant thinkers and their families found refuge through this assistance. More than two hundred academics were found places at universities outside Germany, including Ernst Chain, for instance, whose work on penicillin with Howard Florey and Alexander Fleming was to lead to their shared Nobel Prize in 1945.

And untold millions of us have benefitted from Chain’s survival, of course.

In 1936 the CBF became part of the Council for German Jewry, which also included the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (‘The Joint’) and the American United Palestine Appeal; today you may know the organisation as World Jewish Relief. By this stage, the group aimed to raise £3 million – a significant amount of money in the 1930s – which was intended to fund refuge for a further 66,000 German Jews.

After the 1938 Anschluss, of course, the numbers of Jews who needed to leave the area increased by tens of thousands. The Council for German Jewry, with Norman Bentwich as spokesperson, tried hard to persuade world leaders attending the Evian conference to introduce less stringent immigration restrictions, but they were unsuccessful. It was only after the events of November 1938 that the British government gave some ground, and allowed into Britain the two large movements of Jewish refugees that are the focus of work such as this – the Kindertransport and Kitchener camp. There were several caveats: that the ‘Jewish community’ should pay for refugees’ travel arrangements to the UK, and for their housing needs and general upkeep while here; and this was only granted on condition that the refugees must be able to show that they would either quickly emigrate elsewhere (in the case of the Kitchener men), or return home to Germany and Austria when ‘events settled down’ (in the case of the Kindertransport).

———————————

When Kitchener first opened in January 1939, the CBF was based in Bloomsbury House in London. By February, however, with the increasing numbers of refugees to whom it needed to respond after the events of November 1938, the CBF moved to larger premises at Woburn House. Both these buildings are situated near to the present location of the Wiener Holocaust Library. Thus, if you live near enough, or are visiting the capital and have an interest in this area of study, you could do worse than spend some time wandering around here, getting a feel for these places where people worked hard to help save our fathers, grandfathers, uncles, and cousins.