Contents

Introduction

‘The Joint’ and emigration from Germany

The Joint in Austria

December 1939

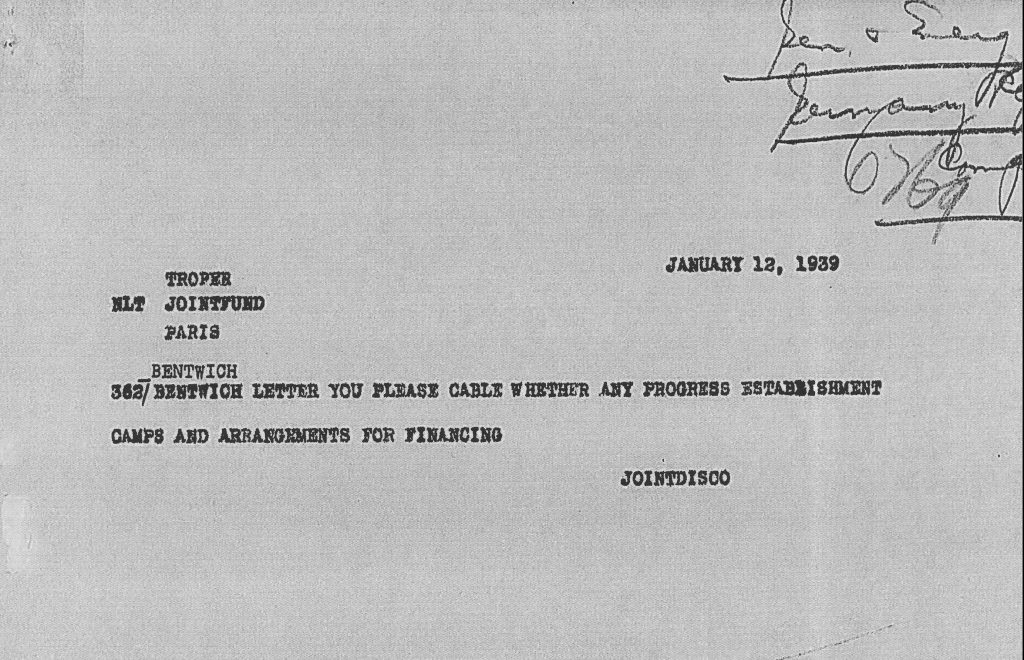

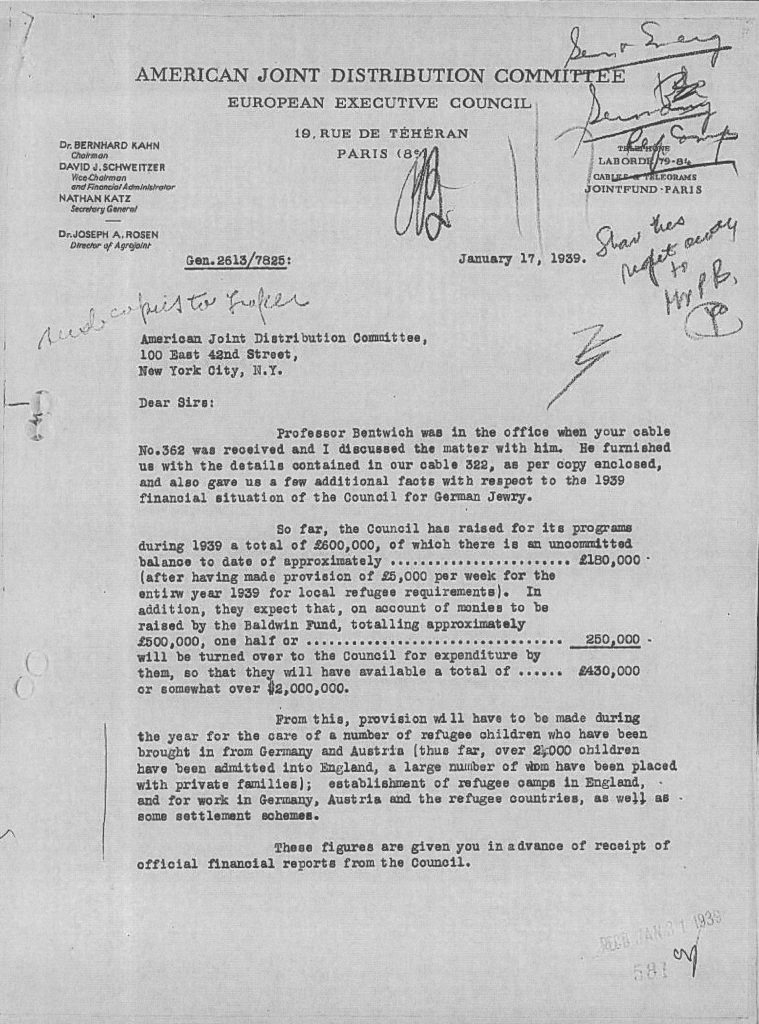

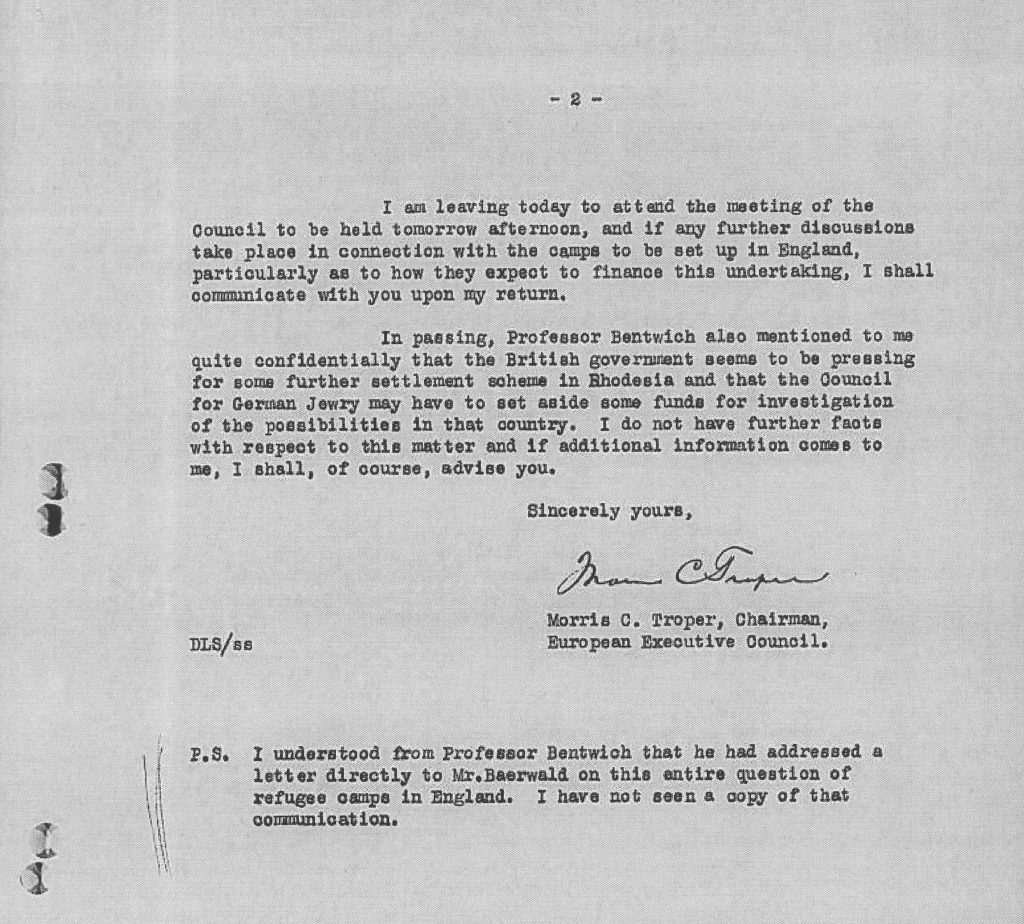

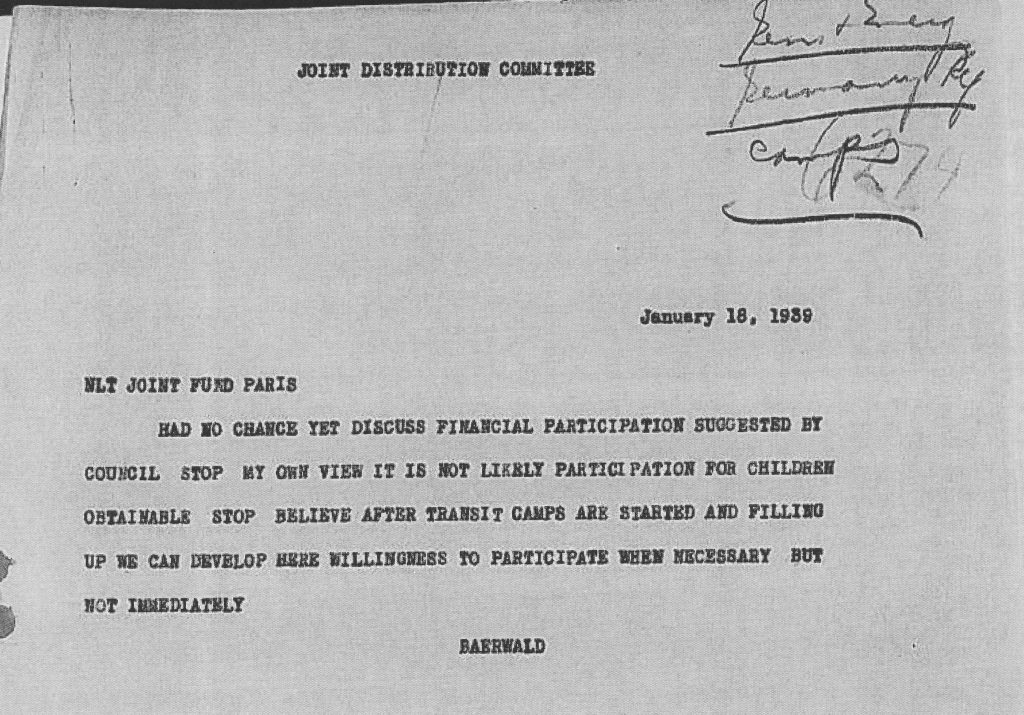

January 1939

February 1939

The outbreak of war: December 1939

January 1940

Postwar era

Introduction

According to Louise London (Whitehall and the Jews, 1933-1948: British immigration policy, Jewish refugees and the Holocaust, Cambridge University Press, 2001.), the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC; also known as ‘The Joint’) was the most active US organization in terms of assistance provided to European Jews during the 1930s.

Founded during the First World War, the JDC was the first American Jewish organization to provide funding for international relief efforts: it “played a major role in sustaining Jews in Palestine and rebuilding the devastated communities of Eastern Europe” (https://www.jdc.org/our-story/): it distributed “millions of dollars in aid” (Amy Zahl Gottlieb, Men of vision: Anglo-Jewry’s aid to victims of the Nazi regime, 1933-1945, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1998, p.35.).

The JDC continued to play a significant role after the First World War, supporting Jews in Palestine and helping to rebuild the ravaged communities of Eastern Europe.

During the 1930s the JDC helped with relief efforts in Europe as legislative restrictions at local and national levels quickly began to take their toll; they assisted with emigration to various countries, including the USA.

After the war, the JDC was a key player in rehabilitation and resettlement activities in Europe and elsewhere, offering much needed social and medical care to concentration camp survivors and the few surviving Jewish communities.

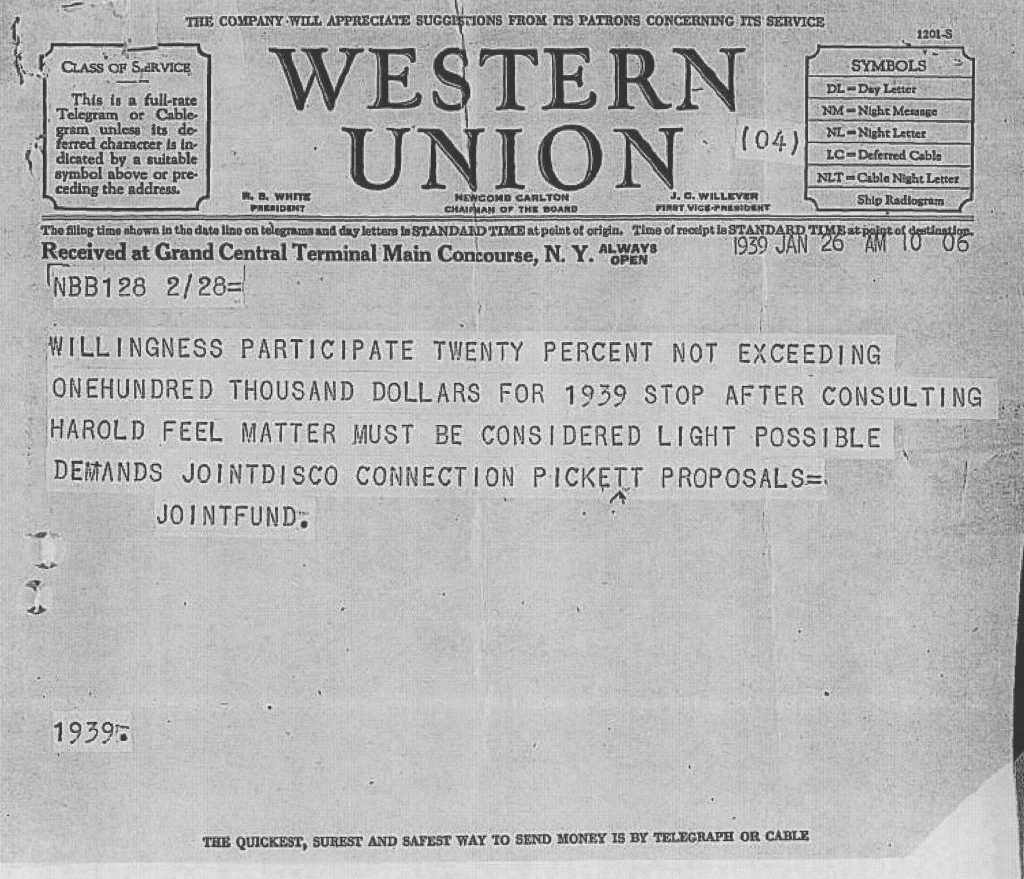

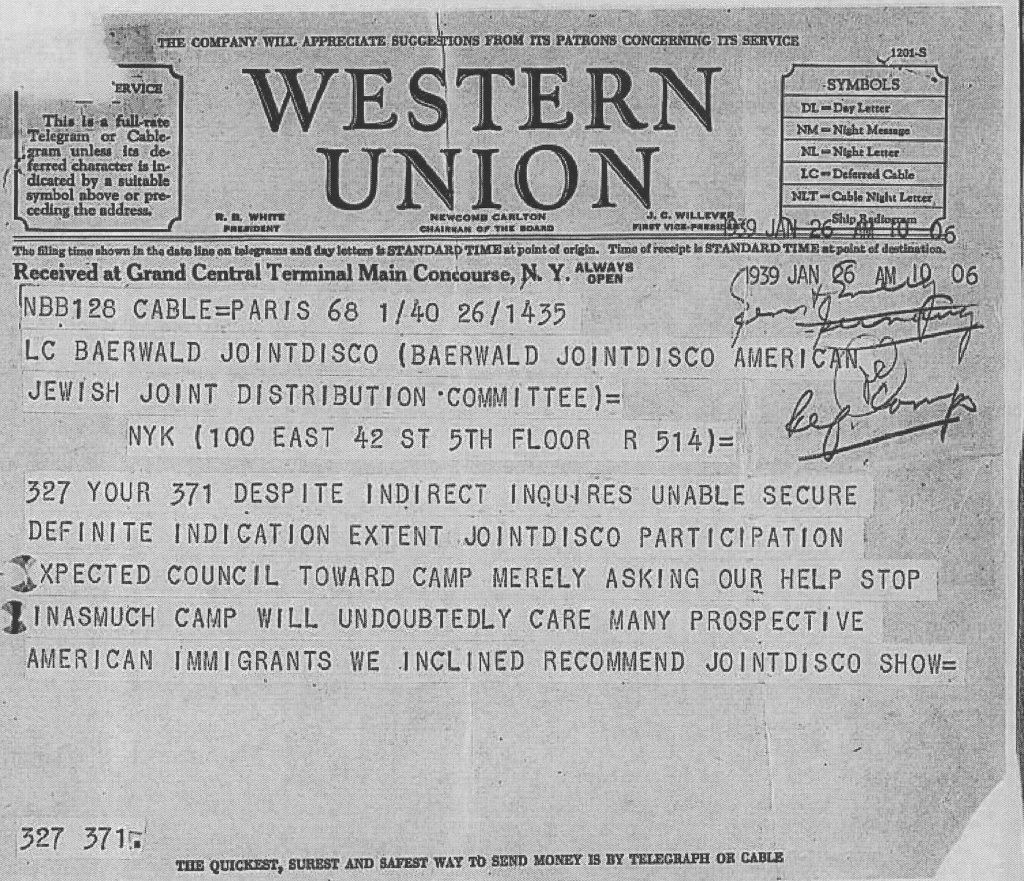

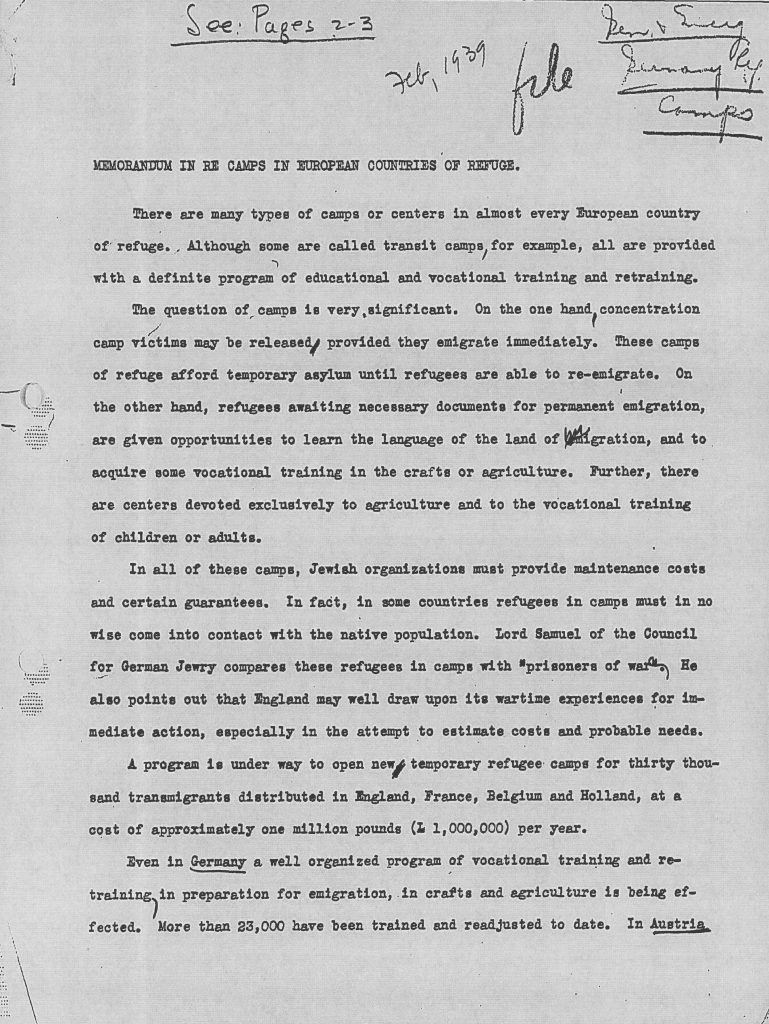

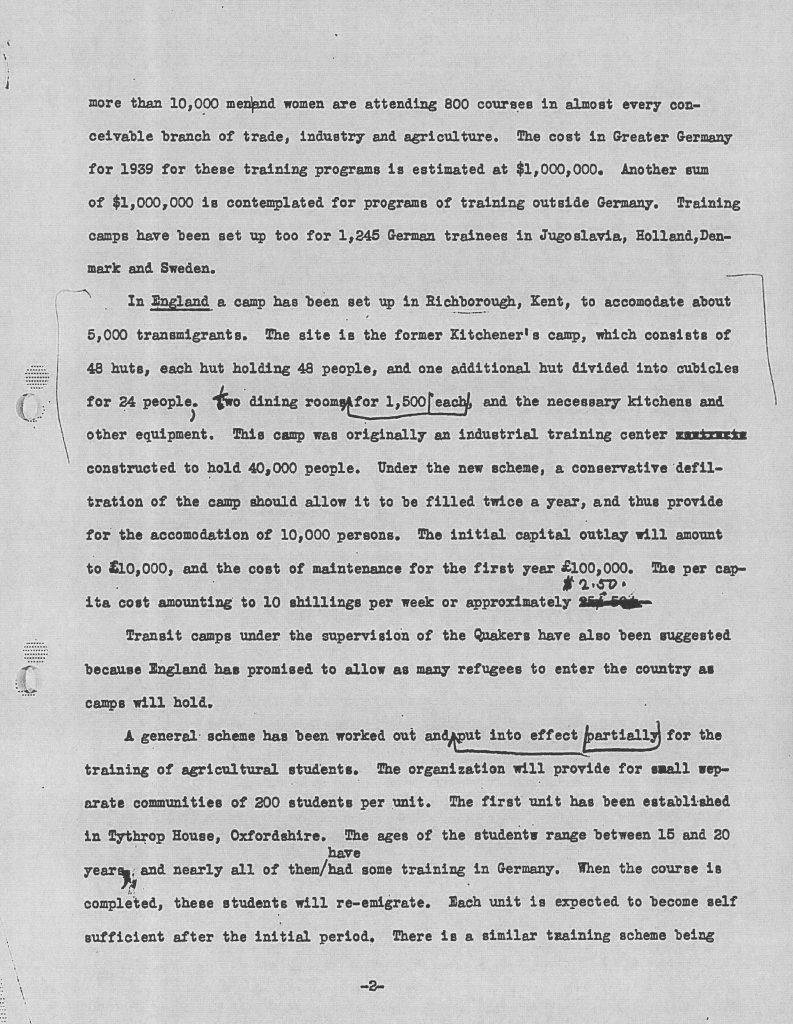

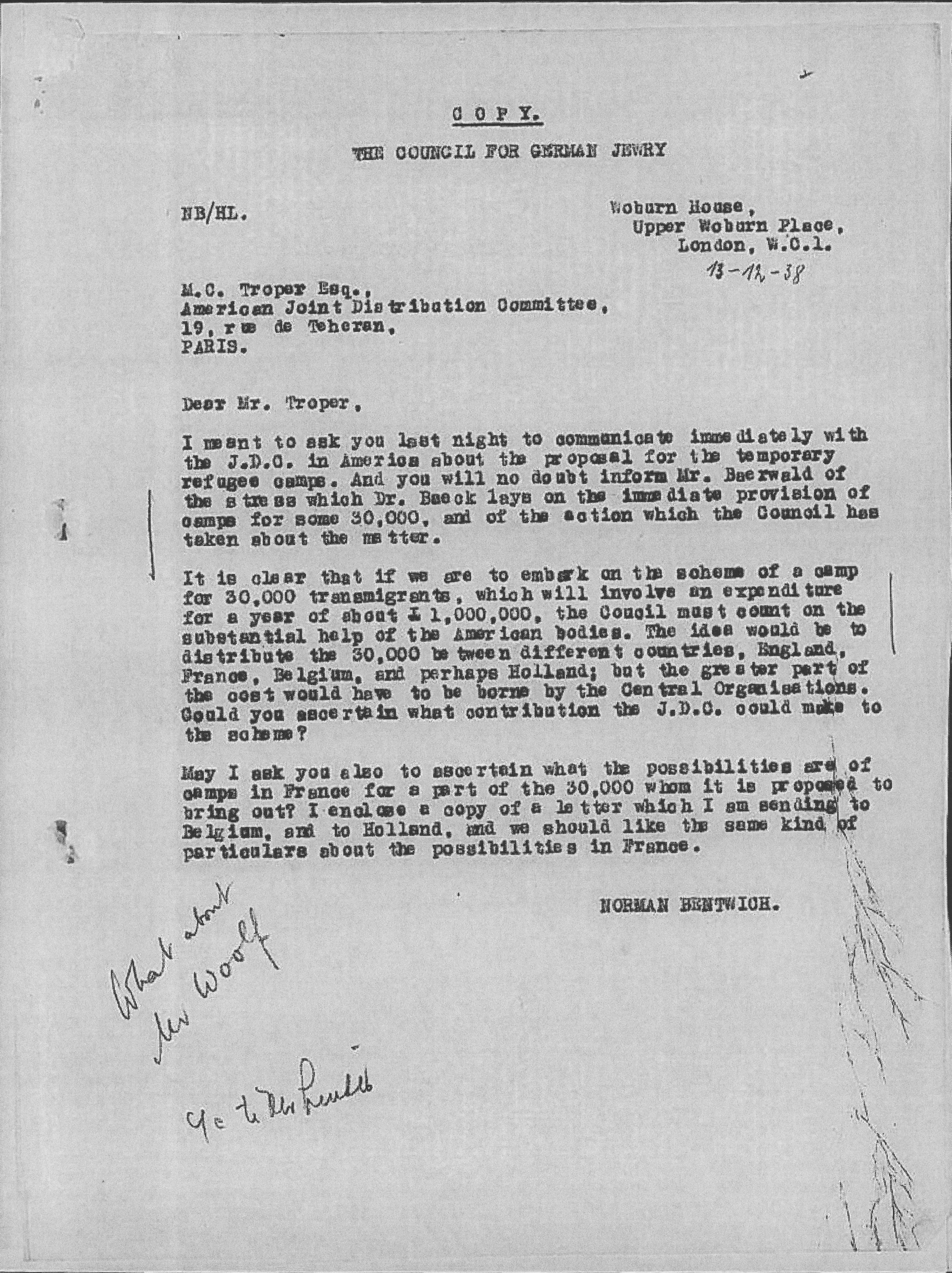

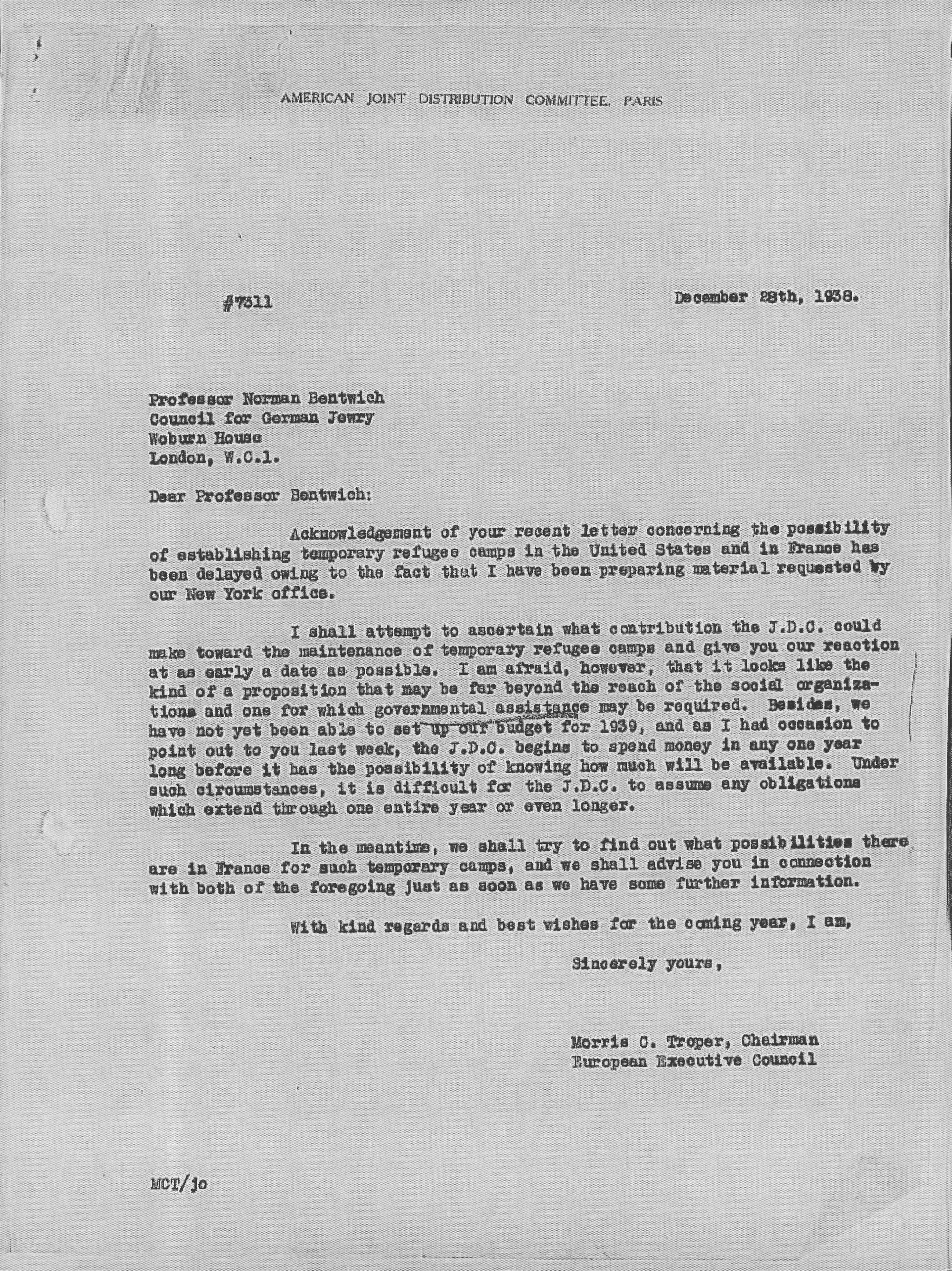

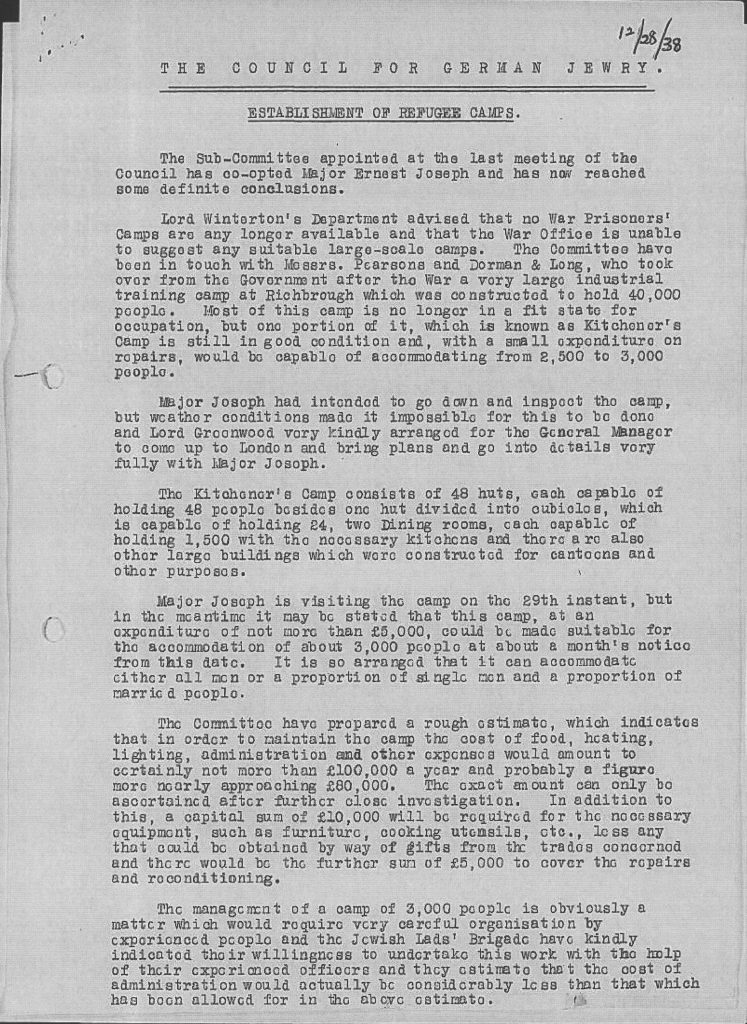

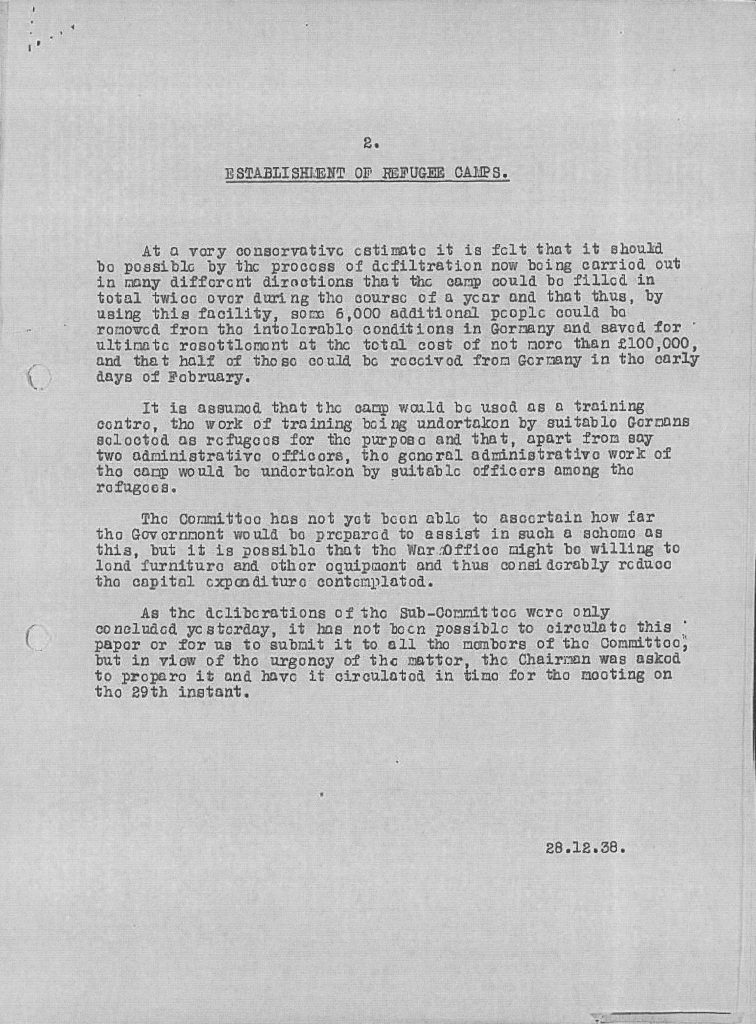

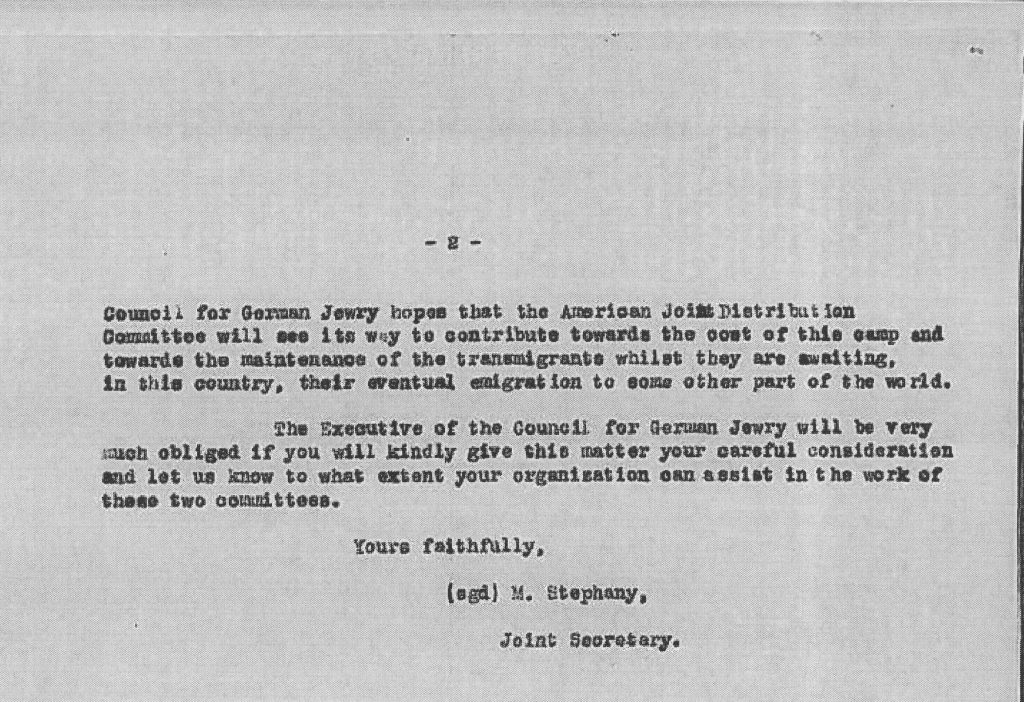

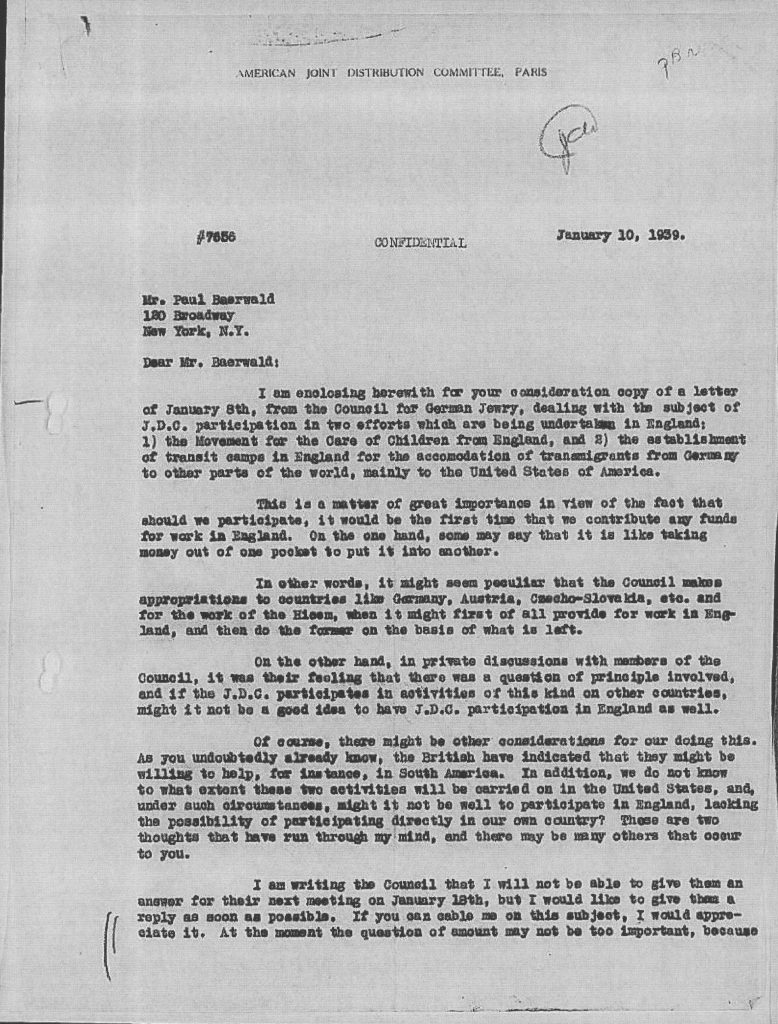

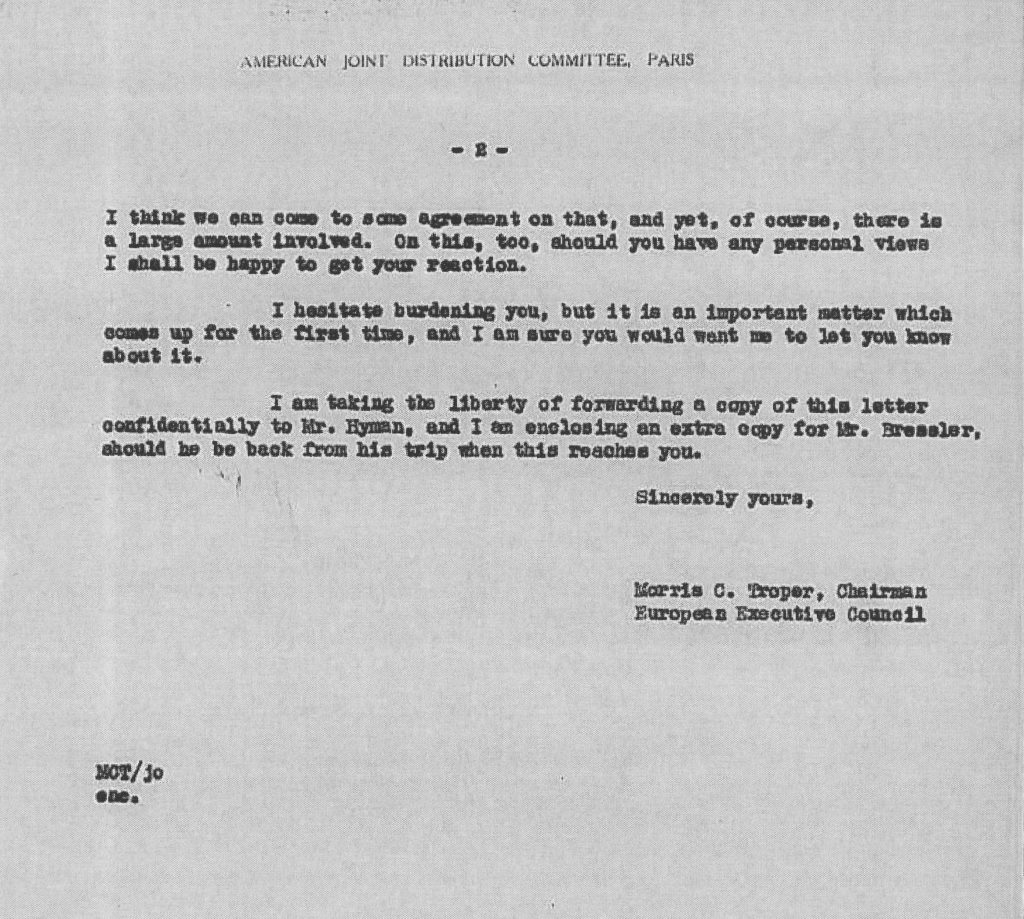

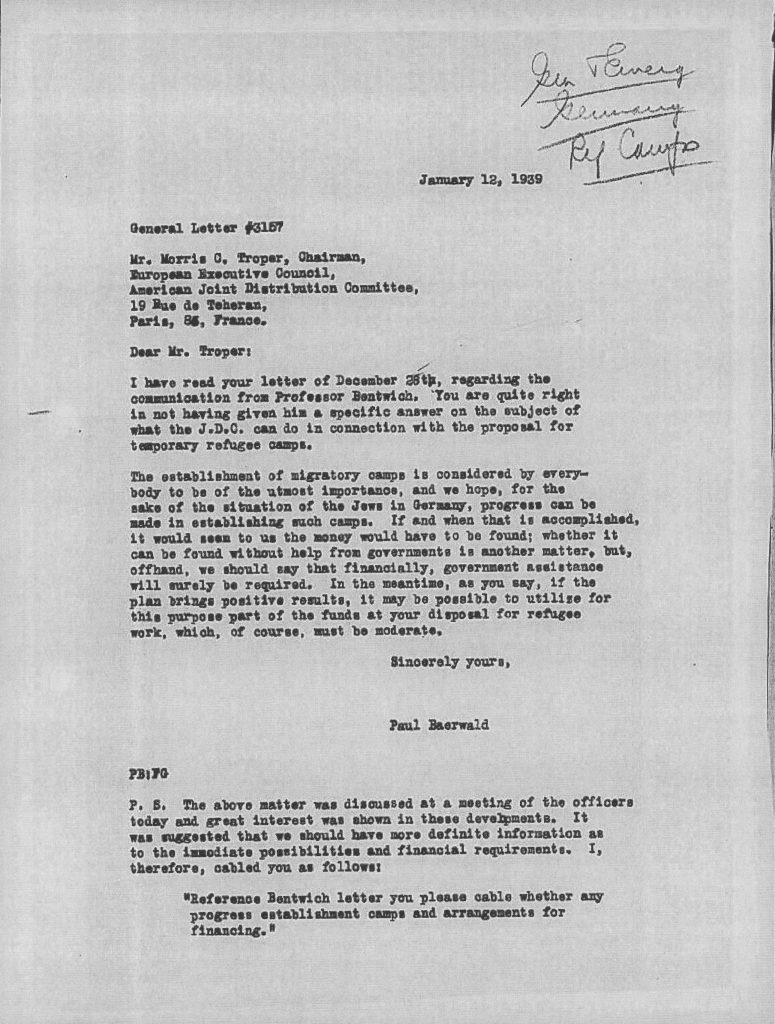

When the Council for German Jewry established Kitchener camp, the JDC contributed financial assistance to the tune of around twenty percent of “upkeep costs” (London, 2001, p.116). Both the JDC and the Central British Fund (CBF) were members of the permanent non-governmental Consultative Council of the High Commissioner for Refugees (Gottlieb, 1998, p. 62) – which both organisations also funded. There was also a contribution made by a Quaker organisation, which assisted some men in getting a place in Kitchener camp.

From October 1933 until his resignation in 1935, James McDonald was the League of Nations High Commissioner for Refugees from Germany. He was sponsored for the post by the JDC, and also worked closely with Norman Bentwich who was his deputy director, and another key figure in the Kitchener narrative (see Clare Ungerson, Four thousand lives: The rescue of German Jewish men to Britain in 1939, The History Press, 2014).

McDonald made frequent visits to Berlin, which generally included meetings with members of the Reichsvertretung der Deutschen Juden; he advised as early as 1933 that “the outlook for the majority of Jews in Germany was hopeless” (Gottlieb, 1998, p. 62).

McDonald stated unequivocaly that aid for emigration was an urgent requirement – an opinion backed by Rabbi Leo Baeck and Simon Marks, founder of the CBF in 1933, who personally donated over £1m to its funds (see Anthony Grenville, Refugees from the Third Reich in Britain, Yearbook of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, 2002, vol. 4, p. 119).

‘The Joint’ and emigration from Germany

Much of the emigration from Germany during the early to mid 1930s had taken place through the efforts and finances of individual families. It had been triggered by both anti-Jewish legislation – at local and national levels – and by increasing violence against Jewish property and people – including imprisonment – and sometimes killings – in concentration camps. During this period, until July 1938, around 150,000 German Jews managed to leave the country (London, 2000, p. 125).

However, aid organizations recognised that as anti-Jewish laws were leaving the Jewish population increasingly impoverished – through the removal of businesses, homes, the means to work, fines, and punitive taxation – the remaining would-be emigrants were likely to require much higher levels of assistance.

As London (2001) notes, the policies subsequently defined by these aid agencies were to play a large part in ‘who’ was rescued – that is – they decided what the criteria would be for a place on a rescue scheme. The larger numbers now assumed to be in need were so great that those who were to be helped could only be assisted towards establishing themselves elsewhere. Helping those who would not ultimately be able to help themselves was not seen as being viable under these circumstances. Thus, the criteria quickly included being of working age, in good health, and so on.

There were many personal and organisational links among the various aid agencies and those who ran them. Otto Schiff, for example, another key member of the CBF, realised early on the risks that German Jews faced. He listened regularly to German radio broadcasts and recognised the “ominous tidings” for what they were (London, 2001, p. 7). A stockbroker in the City of London, and part of a rabbinical and philanthropic family with origins in Frankfurt, Schiff had come to Britain in 1896. He and his brother Ernst had aided thousands of refugees in getting from Belgium to Britain during the First World War.

During the 1930s Schiff was in close contact with Rabbi Dr Leo Baeck, President of the Reichsvertretung der Deutschen Juden, and between them they made the decision to assist Jews wishing to leave Germany.

Dr Bernhard Kahn, who started work with the JDC in 1921, was also in constant contact with Baeck. He was Director of European operations for the JDC, and had strong links with the various German Jewish aid agencies.

According to Gottlieb (Gottlieb, 1998, p. 35), formal contact between the CBF and the JDC began in July 1933: extended family and business connections among the board members made this an obvious link in many ways.

During the early to mid 1930s in particular, however, the JDC was struggling to raise funds to help European Jews. The economic situation in the USA was terrible, and getting individuals and institutions to focus on contributions for people living on a different continent was problematic. James Rosenberg, a member of the executive committee, stated that because of the Depression in the USA, and the concomitant anti-semitism, they “felt it unwise to publicise the large sums it sent to Europe for aid to Jewish communities” (Gottlieb, 1998, p. 34).

Meanwhile, back in Britain, the CBF continued to be concerned about the increasingly precarious position for German Jews, and believed they should expedite plans for emigration and ask US Jews for support. McDonald encouraged Marks, Lord Bearstead (another senior member of the CBF), and Sir Herbert Samuel to visit the USA, meet Jewish leaders, and attempt to gain further JDC support for the plans outlined by the CBF.

"They addressed large gatherings of community leaders and other interested groups, and they received national press coverage and made five nationwide radio broadcasts. Sir Herbert Samuel also met with President Franklin D Roosevelt, who assured him that American Consuls in Germany were sympathetic towards Jewish visa applicants, which, sadly, was not their experience. US Secretary of Labor, Frances Perkins, requested that no attempt be made to dump unprepared or undesirable immigrants on the United States and this was agreed"(Gottlieb, 1998, pp.66-67).

The resulting relationship became known as the Council for German Jewry. The individual groups remained independent of each other, consisting of the CBF, and the JDC, as well as Zionist and other organizations (Gottlieb, 1998, p. 68). They intended to assist around 20,000 to 35,000 people each year to emigrate – mainly, it was assumed, to Palestine.

They aimed to raise £3 million ($15 million) to this end.

The Joint in Austria

Austrian Jews experienced the onset of Nazi policy quite differently to German Jews: the Anschluß came suddenly and with it the full force of the legislation that had taken place over a number of years in Germany. According to Pamela Shatzkes (Holocaust and rescue: Impotent or indifferent? Anglo-Jewry, 1938-1945, Valletine Mitchell, 2002.), people dependent on relief for the basic necessities doubled to over 60,000 when the Anschluß took effect: “by the summer of 1938, over 60 per cent of Austrian Jewry was partially or entirely dependent on organisational support” (Shatzkes 2002, p. 53).

The Jewish community in Vienna was largely supported by the Council for German Jewry (of which the JDC and the CBF were a part). They ran soup kitchens, training schemes, and emigration offices, among other relief efforts.

Council for German Jewry Minutes, 29th March 1938 "Mr Otto Schiff reported that ... the situation [in Vienna] was desperate, that practically all the leaders of the Jewish community were either in prison or under house arrest, and that 22,000 persons (mostly Monarchists) ... were in prison in Vienna. All the Jewish institutions were closed down, except the soup kitchens."

"Mr Norman Bentwitch gave an account of his visit to Vienna and said that the position was exceedingly bad. The policy of the Nazi government was definitely to force Jews to leave the country and the confiscation of their property and businesses was a means to this end ... Ten thousand people were at present being fed at the soup kitchens and it was estimated that 12,000 a day would require assistance during the course of the next two or three weeks. At the moment the Kultusgemeinde estimated that they were spending £10,000 in retraining and 200 young people had already been sent to training camps in Germany. They wanted to retrain between 2,000 and 3,000 young people."

"It was felt that by ... selling a portion of the dollars which were provided by the British section of the Council for German Jewry and the American Joint Distribution Committee ... the Kultusgemeinde would be able to obtain the sum of RM 1,500,000 for $200,000, which it was proposed should be placed at the disposal of the Kultusgemeinde for the months of September and October. Towards the sum of $200,000 the American Joint Distribution Committee desired the British section of the Council for German Jewry to provide one-half, and the AJDC the remaining half; but the Officers felt that, in view of the demands on the resources of the British section, the maximum that they could recommend would be for the Council to provide one-third, or £13,500 for this purpose."

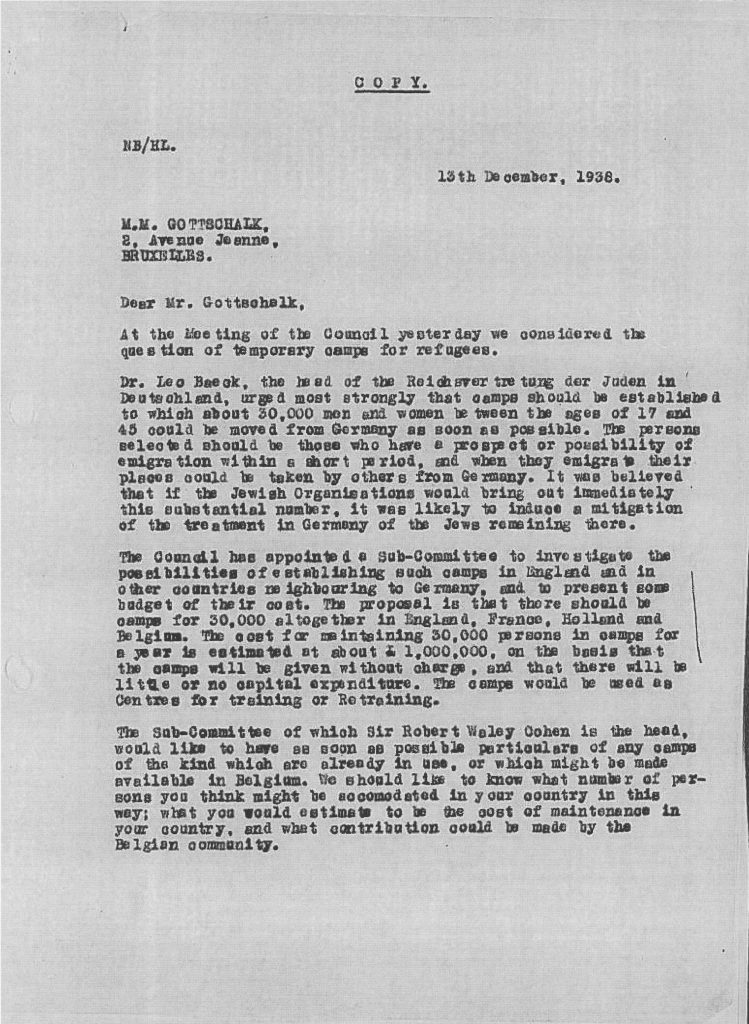

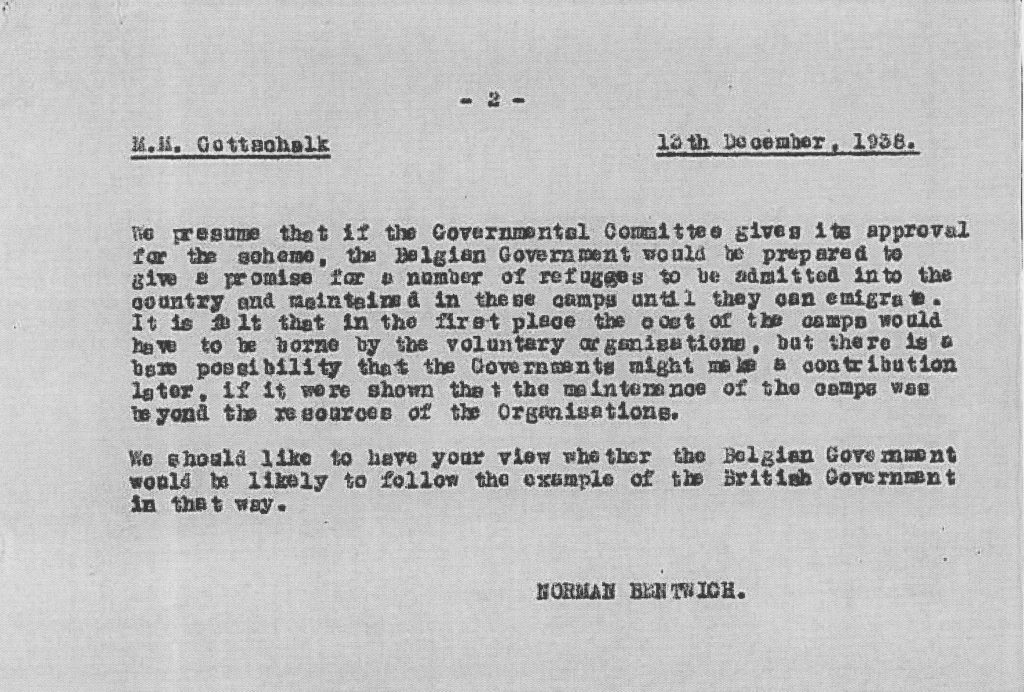

December 1938

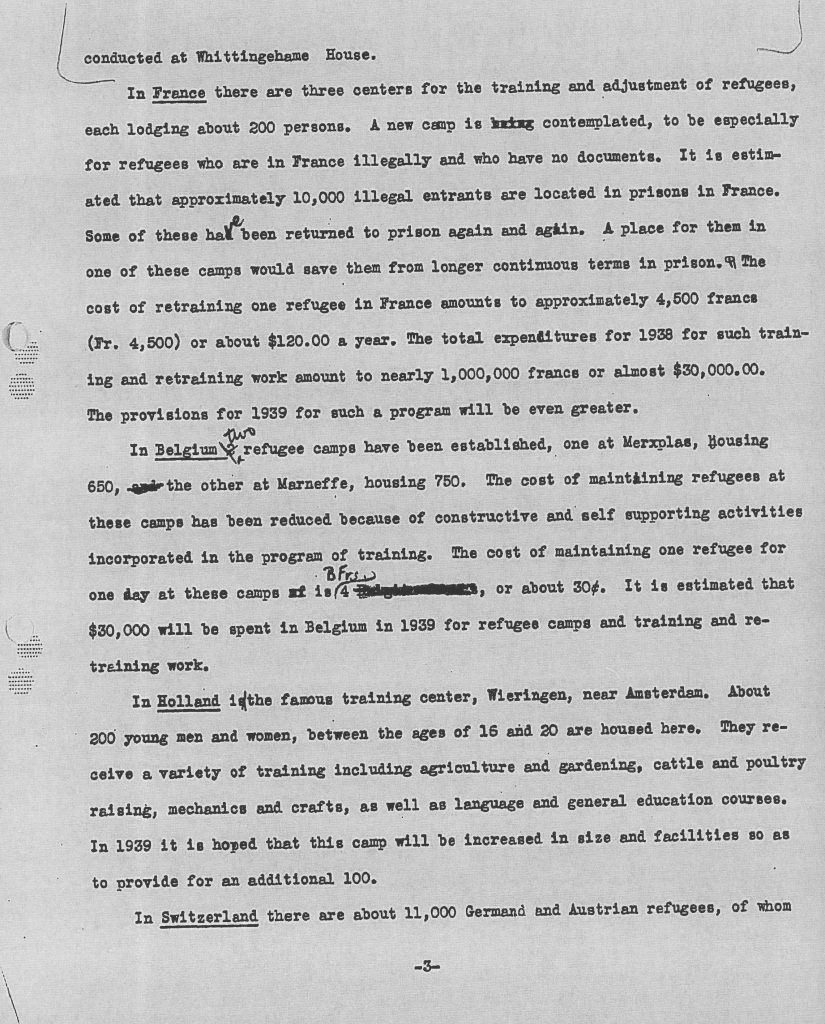

January 1939

February 1939

The outbreak of war: December 1939

January 1940

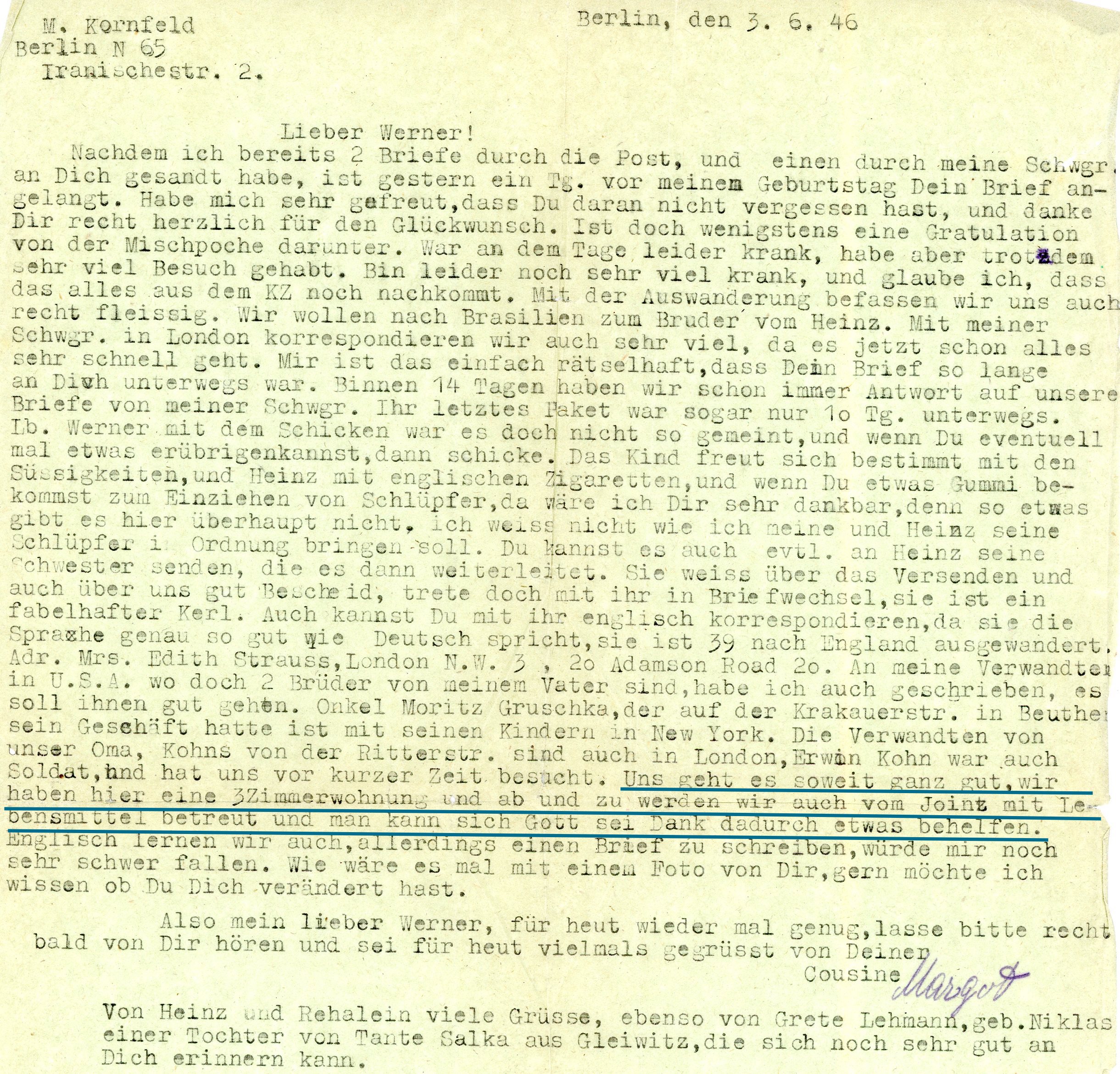

Postwar era

The work of the JDC continued in the postwar era, in aiding the new communities of Israel, Jews in North Africa and Muslim majority states, and with relief work in the former USSR. When the USSR collapsed, the JDC was able to step into Eastern Europe more broadly, helping to sustain now-elderly survivors of the Shoah who had so often been left destitute.

“Comprising the organizational records of JDC, the overseas rescue, relief, and rehabilitation arm of the American Jewish community, the JDC Archives houses one of the most significant collections in the world for the study of modern Jewish history. With records of activity in over 90 countries dating from 1914 to the present, the JDC Archives is an extraordinary and unique treasure in the archival world. The JDC Archives is located in two centers, one at JDC’s NY headquarters and the second in Jerusalem, and is open to the public by appointment.” (https://archives.jdc.org/about-us/).

![Richborough camp, JDC, Cable, Troper, Baerwald, Funding Discussion not possible before Executive meeting, "All realize importance [of] camps", What amount needed, 24 January 1939](https://kitchenercamp.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/fullsizeoutput_2025-1024x833.jpeg)