We’ve been starting to take a look at some of the varied outcomes for Kitchener men when war broke out.

I particularly wanted to get some information uploaded about the Dunera voyage, which has now been started. We’ve had a few Australian families in touch, so this has been an important area to get underway.

We’ve also just had our first Canada descendant contact, so at some point soon we will add that to the research too.

………………………………….

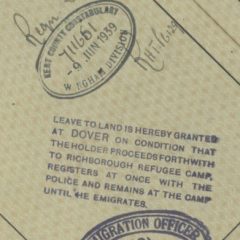

In late September 1939, after Britain had declared war on Germany, Clare Ungerson (2014) reports that “six senior lawyers proceeded to Sandwich to investigate the men’s loyalty and decide, under the Aliens Act of 1919, whether they were ‘friendly’ or ‘enemy aliens’. The lawyers were provided with special offices at the camp to undertake the interviews and they seemed very well informed about the structure of each of these men’s previous lives” (Ungerson, p. 144). She goes on to observe, “The Kitchener men understood that their loyalty to Britain was being investigated, and, as a consequence many of them told these lawyers, in graphic detail, the terrible ordeals to which they had been subject in their countries of origin” (p. 144).

These alien tribunals were established to ascertain which Germans living in Britain were to be categorised as ‘friendly’ and which were to be deemed ‘enemy aliens’. Around Britain, approximately 65,000 were initially categorised as ‘friendly’.

When France fell in the middle of 1940, however, the government became nervous about invasion, and many Germans, Italians, and Austrians came under suspicion. The decision was made to intern in the UK, or to deport (for internment) to Canada and Australia.

………………………………….

By the end of the tribunal process, all but two of the Kitchener men were deemed to be ‘friendly aliens’. Approximately 1,500 attempted to join the Auxiliary Pioneer Corps, although some did not pass the medical, and some were too young, or too elderly.

In the end, six companies were formed here, between January and May 1940, of three hundred men each, and Kitchener became a PC training camp, in the main.

Most of the men training here had been in the camp to start with, although some were sent from other parts of the UK, and not all were Jews or refugees. Quite a large number of the German and Austrian Jews changed their names to something more English sounding around this time, being persuaded that it would be better for them should they be captured.

The men who did not join up for many and varied reasons – religion, being too young or too elderly, fears for their family, poor health, or, for around 700 men, being in possession of a visa for immediate departure, for example – were also kept busy. They assisted in the running of the military side of the camp, with many undertaking catering and repair duties as before.

There was a considerable amount of tension through these months because the remaining men who had not enlisted expected to be able leave the camp, but the camp authorities had decided that in such a context, for the time being at least, they needed to stay where they were. When good relationships between the organisers and the men broke down for a while, Julian Layton was brought back to run things, and matters quietened down again into May and June 1940.

Of course, in the wider world at this time, the British Expeditionary Force was suffering catastrophic defeat in France, which the Pioneer Corps men were caught up in. Consequently, at the end of May 1940, as Ungerson reports (p. 164), the military and civilian camps at Kitchener were closed. A wide area along the east coast was now a protected area and all aliens were to be removed from it. Many were interned on the Isle of Man and elsewhere.

In August 1940, the Kitchener men who had been internees were given a second chance to enlist, which quite a number took up. However, the large numbers marked for continued internment meant that the government sought other places to put people, and they came to arrangements with Canada and Australia that many thousands would be sent for internment overseas.

After all these men had been through, often since 1933, in their home countries, and through their months as refugees in a foreign country, stateless and kept far from their endangered families, some of the Kitchener men were now to set sail on what was to be the Arandora Star’s final voyage.

Heading for Canada, the Arandora Star carried Italian and German POWs as well as internees. Around 734 interned Italian men, 479 interned German men, 86 German prisoners of war, and 200 military guards boarded the ship between 27–30 June, 1940; there were also 174 crew members.

On 2 July the ship was torpedoed by a U-boat, and 805 people were killed (source: Wikipedia).

Among the survivors were some Kitchener men, some of whom continued to experience yet further – for most of us, unimaginably – dreadful outcomes.

Some of them were next put on HMT Dunera, bound for Australia.

………………………………….

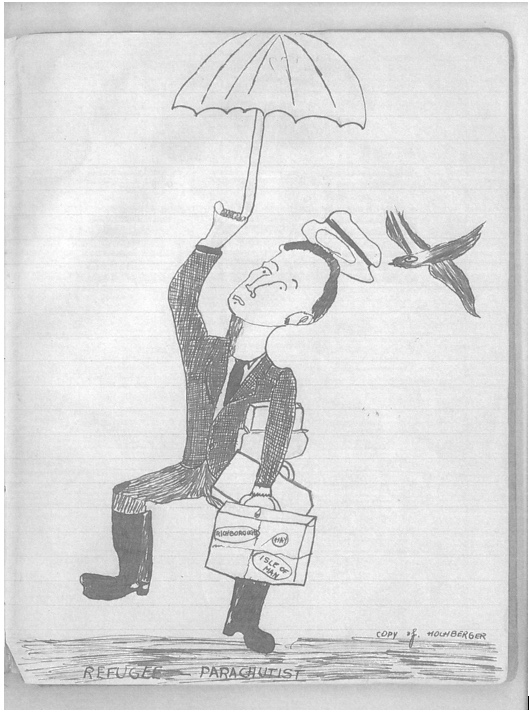

The project is currently receiving some extraordinary materials from a descendant family that had a relative on HMT Dunera. His remarkably measured accounts of Kitchener, internment on the Isle of Man, the Dunera voyage, and internet again in Hay in Australia are recommended reading for anyone with an interest in this area.

Submitted by the family of Moshe Chaim Gruenbaum