As the first chill of autumn starts to make itself felt in the south east of England, I have been uploading some letters from a Kitchener family that remind me how much more brutal the winter chill must have felt before the days of central heating and double glazing.

The winter of 1939-1940 was one the coldest in Britain in nearly 50 years. Our fathers and grandfathers were living in wooden huts and, if in the Pioneer Corps at this point, in tents in fields, during weather marked by freezing temperatures, frosts, fog, and heavy snow.

By January 1940 a temperature of minus 23 had been recorded in Wales, and in Canterbury, which is only about 16 miles from Sandwich, the temperature had dropped to minus 20. Even London’s vast Thames river froze for an 8-mile stretch. Around Folkestone and Southampton – also near to where hundreds of Kitchener men were living, and where some Pioneer companies were stationed at this time – the sea harbours were covered with ice.

Towards the end of January a snowstorm hit the country: northern England had between 30-60cm of snow, and snow was deep enough to form drifts in the centre of London. Eastbourne recorded 25cm at ground level, Malvern 60cm, and Exmoor had drifts of up to 2.5m.

Monthly Weather Report of the Meteorological Office, January 1940

A brief thaw in February was followed by further freezing temperatures and further snow and ice.

Kitchener camp, Monthly Weather Report of the Meteorological Office, February 1940

Although bad weather reports were largely banned as part of the ‘Careless Talk’ campaign, local Kent newspapers report fishermen having to be chopped out of their boats after water came up over the sides and froze them into place (Thanet Advertiser, Friday 12 January 1940, p.8); football pitches are described in terms of being slippery and treacherous (Kent & Sussex Courier, Friday 12 January 1940, p.9); and occasional reports appear of the problems caused by the bitter conditions for those assisting the armed forces: “the fisherman … now gallantly serving in the Dover Patrol, unceasingly performing the strenuous and dangerous task of keeping the channels clear of mines for our ships in this bitter weather”.

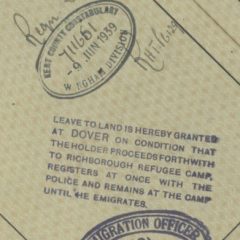

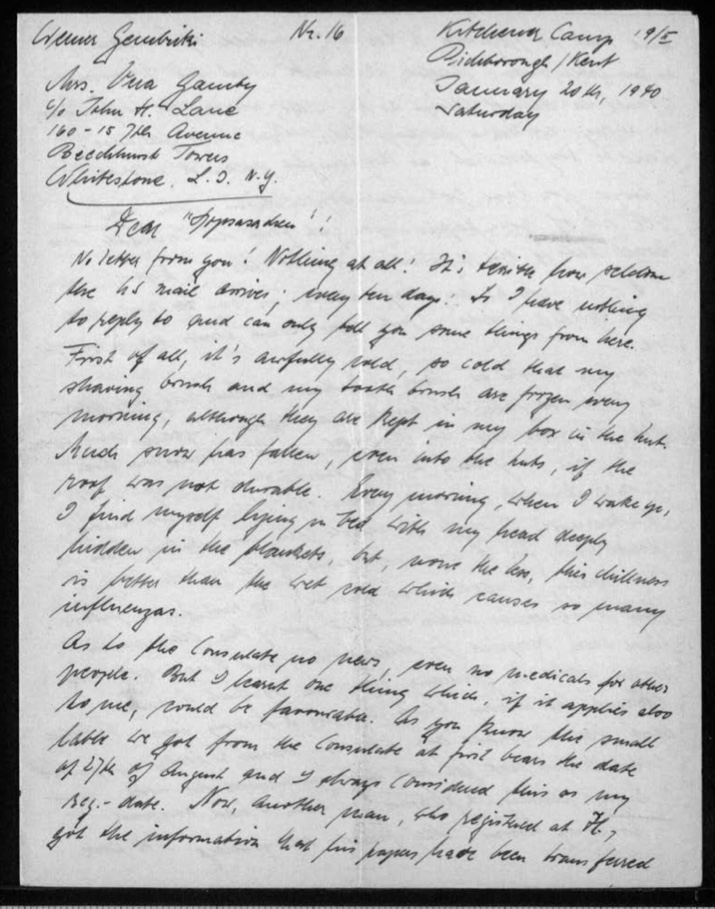

Meanwhile, in Kitchener camp, the hundreds of men waiting for onward migration, or other outcomes, were also suffering from this atrocious weather, as we can read in a letter home (below), for example, from Werner Gembicki to his wife, who has already made it out of Germany to the safety of the USA.

Letter from the Werner and Vera Gamby Family Collection, AR 25617, Box 1 Folder 10 With the kind permission of the Leo Baeck Institute, New York

The weather reports linked to in the post above are under Crown Copyright (Open Government) License: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/

Other weather information on this page is drawn from Netweather.tv

Newspaper reports are from The British Library’s ‘British Newspaper Archive’