So, why do I keep mentioning the Wiener Holocaust Library?

What is it – and what is its relevance to this project?

A personal perspective

Many years ago, I took a side-step away from my usual research area and attended my first academic conference on the Holocaust – at which a holocaust survivor and theorist was to be the keynote speaker.

The conference was run from the Wiener’s previous location, rather than the present Russell Square townhouse, but the foundation stone of my interest in the Wiener Library was laid there and then.

I suppose it was a combination of things, not just my encounter with the keynote speaker and delegates. It was also to do with being in the midst of the collection rescued by Alfred Wiener, and in the midst of the silent researchers, working away, who took this subject seriously.

It was also to do with the small brass memorial plaques (now in the Reading Room at Russell Square) – a discreet and moving testament to people’s loss in the Shoah; at the time, I’d never seen anything like that before. And it was to do with my strong sense that this was the beginning of something – although it was to be many years before that ‘something’ would be realised.

When it was realised, it was to be a journey into our family’s loss that would always be framed from time to time by my encounters with the Wiener Library and its modest, dedicated staff.

Who was Wiener?

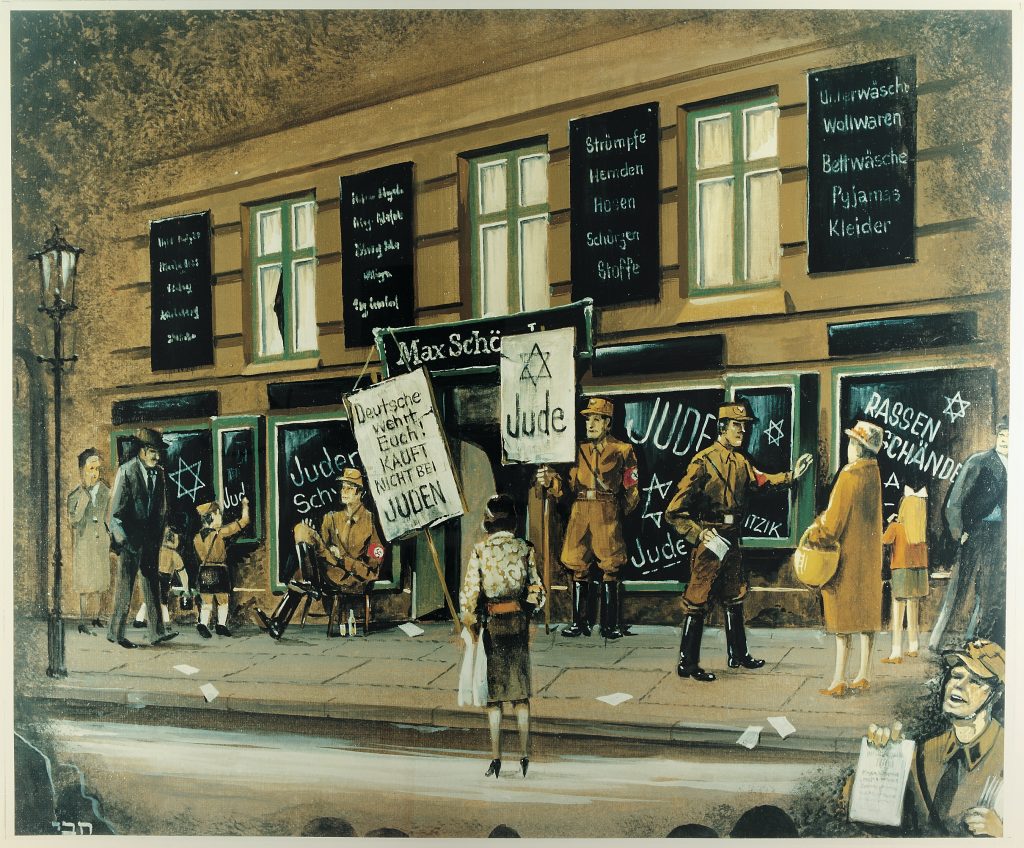

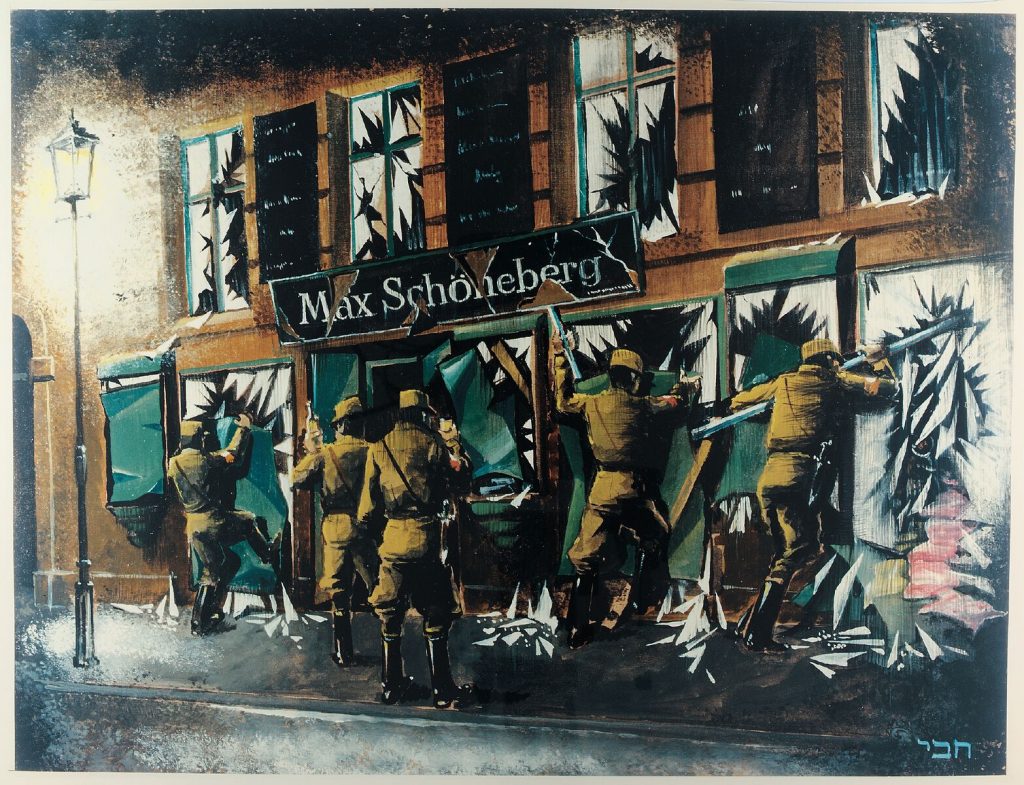

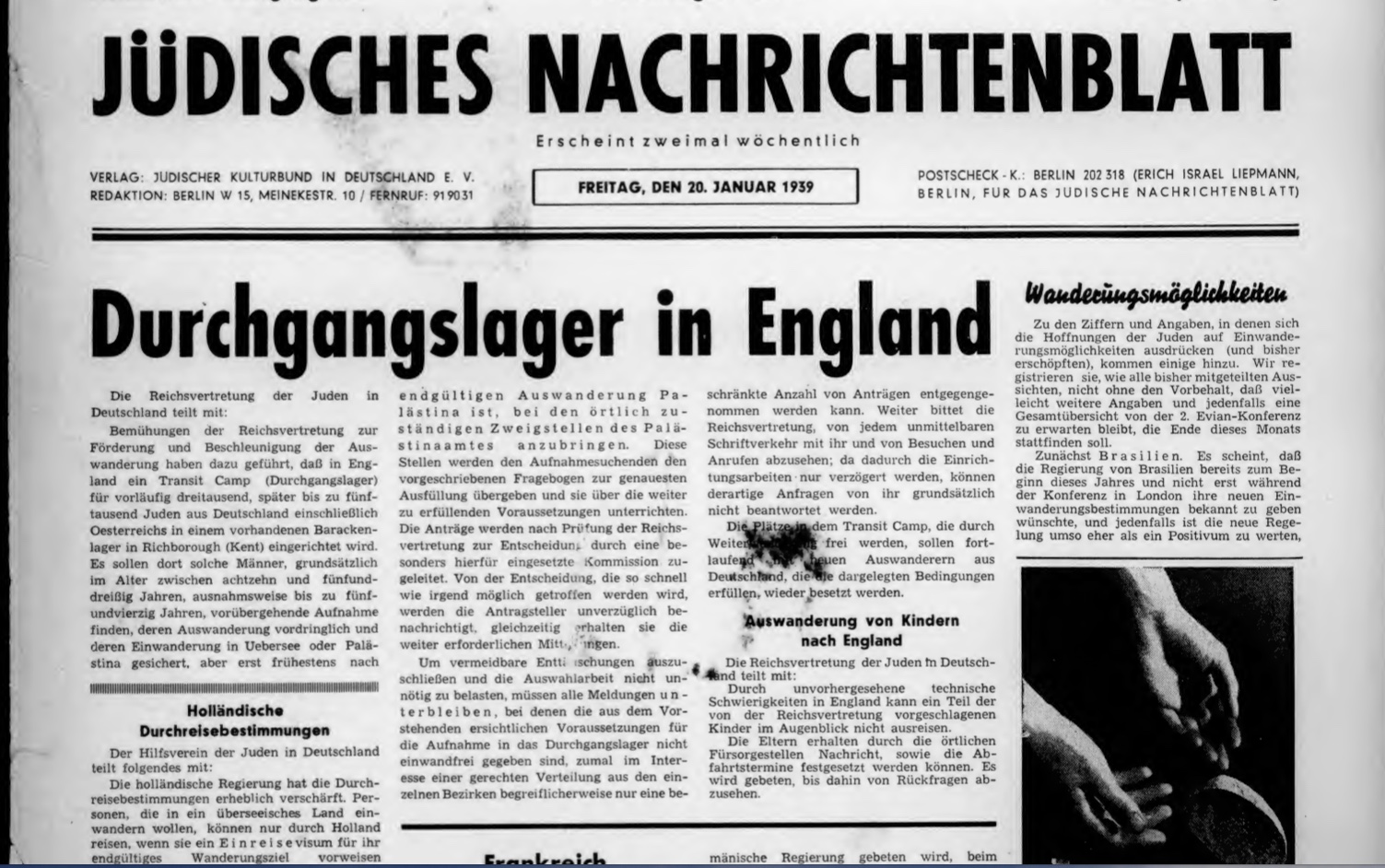

Alfred Wiener was a German Jew who recognised early on the dangers of the right-wing turn in German political life; by the time Mein Kampf was published in 1925, his understanding of the risk was already heightened. In response, Wiener began to collect information in an effort to counteract the growth of the far right, although his activities put him and his family at risk when the National Socialists gained power in 1933.

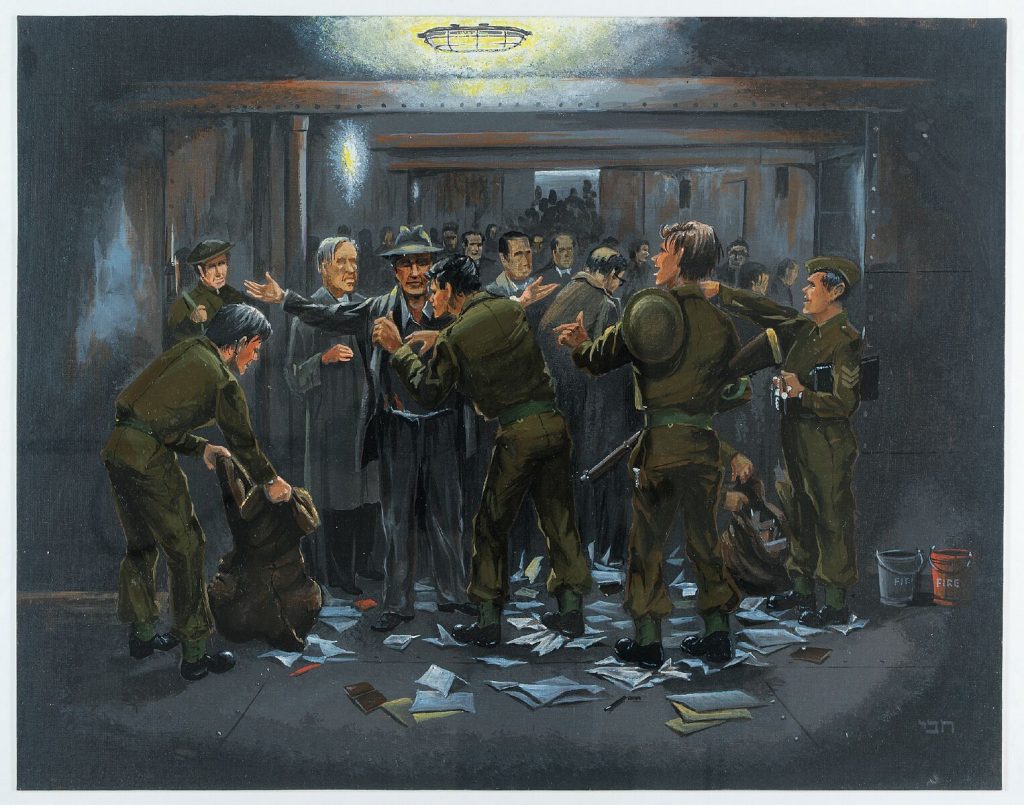

Thus, the Wiener family left Germany and settled in Amsterdam for a time, where Wiener continued his work. Establishing the Jewish Central Information Office (JCIO), Wiener’s collection of books and materials continued to grow: by 1938 there was in excess of 8,000 books and other materials, and a staff of ten assistants.

As conditions deteriorated further with the events of November 1938, Wiener prepared to move his now substantial archive to London, which was finally achieved in summer 1939. However, although Wiener managed to leave in time, his wife and daughters did not, and his wife Margarethe died shortly after liberation from Bergen-Belsen in 1945.

After the war, the Wiener Library (as it was now known) assisted with the War Crimes trials at Nuremberg, collected Holocaust testimonies, and was a key shaper of Holocaust studies.

Today the library is recognised as the world’s oldest institution for the study of the causes, processes, and legacies of the Shoah. It houses “over one million items includes published and unpublished works, press cuttings, photographs and eyewitness testimony” (Wiener Holocaust Library – About us).

And how does this relate to Kitchener camp?

From the offices of the JCIO in Amsterdam, Wiener and his colleagues also collected over 350 eyewitness accounts of the events of November 1938, from throughout Germany and Austria. The accounts were collected in the form of reports, interviews, letters, and newspaper articles. In 2013, in an extraordinary undertaking, Ruth Levitt began a project to translate these hundreds of testimonies into English, and they are now available online and in book form.

The immediacy with which these testimonies were collected in the weeks and months following the November 1938 events makes this a unique undertaking, and it is a significant achievement by any measure, as are the translations, the book, and the searchable website.

But I like to think, too, of this important collection being brought out of Europe by Wiener and his colleagues via one of the routes that our fathers and grandfathers took on their way from ‘Greater Germany’ to Britain during that same summer of 1939 – when so many Kitchener men were travelling this way.

Imagine – a Kitchener descendant’s father or grandfather may well have been on the same train as Wiener and his collection, and some Kitchener man’s testimony of November ’38 may now be translated and housed in the Wiener library collection.

And if all that isn’t enough to start to understand why I keep mentioning the Wiener Library, then may I return, briefly, to my more recent personal experience of it – and to an account that I have written elsewhere.

Because this library is where the uncovering of my own family history eventually began. And that is also the story of how we’ve all ended up here – on this webpage.

………………………………………

In 2014, while paying a first visit in many years to the Wiener Library, London, I was looking at their website when I got my first intimation that the International Tracing Service existed (https://fromnumberstonames.com/holocaust-research/arolsen-archives/) at Bad Arolsen.

With what little information I had at that stage, I emailed off some search forms. I can’t describe what this meant – the thought that I might finally get some information about my family.

However, in one of life’s frustrating moments of irony, my longed-for encounter with history was delayed by technology, and an auto-reply ping-back stating that there was a backlog of search requests. They would respond to me as soon as they could … which might take a few weeks or months.

I then discovered by chance that a copy of the vast ITS database was held at the Wiener Library. It transpired that I could submit a request for tracing with the Wiener, but it was also possible sign up to a session to learn how to search the database myself.

Being of a somewhat impatient nature, I opted for the latter, although if I thought that this would be a speedy resolution to my ‘need to know’, I was to be was sorely mistaken …

The ITS database (ITSD) is vast and rather unwieldy to use – and many of the records are still to be uploaded at Bad Arolsen, Germany, let alone at the Wiener, which gets tranches of records to upload some time after Arolsen has uploaded at their end of things.

And then there’s the ITSD itself, which is something of a challenge to use, shall we say.

Having said that, the ITSD is also extraordinary. Every search starts with the Central Name Index – the key to the documents that are buried here. At the time of writing, the database includes around 50 million reference cards concerning the fate of around 17.5 million people.

Now read that last sentence again …

Once the initial record cards have been located, the tricky part starts – trying to understand the ancient file references that can be found on the cards, and then trying to find the documents that the file numbers refer to …

I shouldn’t complain, though: many will find nothing here to satisfy their need to know, despite the size of the database. As we know only too well from this Kitchener work, so many records were destroyed during and after the war. With the ITSD, whether family members appear in the database rather grimly depends on how they died (or indeed, if they survived).

Anyway, in our family context, I was able to find some documented information.

My own feeling towards the ITSD has been one of both gratitude and, at the same time, of frustration and disbelief that any database still functions like this: it feels like it was built 20 years ago. Still, without it, I wouldn’t have got nearly so far with our search.

And I must admit that part of the appeal, as time has gone by, has been a sense that it’s a bit like being involved in the world’s slowest detective story.

The world slows down, as the ITSD boots up, and history unwinds before my eyes and searching fingers.

There’s an appeal in that too, it seems.

In the end, I decided that after all these years I could afford for it to take a little longer.

And perhaps this long, slow, complex search is the appropriate mode in which to search through our long, slow, complex history.

UPDATE: The International Tracing Service has been renamed since I wrote this post. It is now known as Arolsen Archives. A vast number of its documents have been digitised and are now available to search and view online, from here: https://arolsen-archives.org/en/

………………………………………

So, having found my first family records via the ITS, with the patient, quietly compassionate help of Dr Christine Schmidt, who was then running the Tracing Service at the Wiener, I went on to spend the next two to three years immersed in ‘the search’ at a broader level.

It was to be a search that would take us on journeys to tiny, one-cow villages, as well as to towns and fascinating cities in Poland and Germany – to places that I had never imagined I would visit. I’ve climbed into locked cemeteries, beaten down long grass and stinging nettles to try to read gravestones, and stood in front of freezing cold tombstones, knowing that I was the first family member to stand there in many, many decades. And I’ve paid quiet tribute to family members at the camp where they died.

More recently – somehow liberated by, while also immersed in, the past, I’ve even started to learn German …

I’ve met almost everywhere an unexpected generosity and kindness towards my ‘need to know’, which in itself has been quite a journey. And I have been recording it all on a website, which I learned to build specifically to be able to keep the family up to date with what I’d found.

Anyway, the family website grew, and people started to get in touch from all over the world: this one had family in the town my grandmother was deported from; this one had family with a shop on the same square that my family had a shop… And so we met up, and had coffee and cake, as our families probably did in the 1920s – in memory of our families’ connections. And this one – Stephen – well, his father was at the same university as mine, and was in the same Kartel-Convent fraternity too; and guess what? They were both at Kitchener camp in Kent …

We chatted a bit on email, and realised that Stephen’s father was mentioned in my father’s letters from all those years ago, and from here came the idea that we should see if any other ‘Kitchener descendants’ were out there too. Who knew? A few might even want to meet for a coffee …

Anyway, I’d reached a part of my father’s history that meant I needed to find out more about what Kitchener camp was, and what it did. And so, of course, I asked at the Wiener Holocaust Library.

And they said – have you read Clare Ungerson’s excellent book, Four thousand lives? Why don’t you get in touch with her …

So you see – none of us would be here today – me writing this and you reading it, were it not for the Wiener Library. Their facilities and responses were the trigger for the organisation of the first meeting of Kitchener descendants in summer 2017, which in turn led to the present project.

Since then, the Wiener has given us considerable help and advice behind the scenes, and they continue to support me in my efforts to further bring together the histories of our Kitchener camp families.

And one day, coming full circle, when I’ve finished my family research, my father’s archive of documents, photographs, and letters will go to the Wiener Holocaust Library. They will go into the care of their dedicated archivists, by whom I know they will be respected and kept safe for future generations of Holocaust researchers.

With thanks

Dr Clare Weissenberg, Designer and Editor, The Kitchener Camp Project

………………………………….

Sources

The Wiener Holocaust Library

Holocaust Memorial Day Trust

EHRI

Wikipedia