Quite a number of descendants have been getting in touch to say they have found a photograph of, or other archival holdings about, Kitchener camp. It’s always great to get this information and to add it to our ever-growing accumulation of Kitchener detail. Thanks for getting in touch with these items – it’s really appreciated!

Over recent weeks and months we have been gradually working our way around archives to collate as many holdings on Kitchener as possible, although you’ll appreciate that this takes a bit of doing! I do have quite a lot of information at this point, however, and as soon as I have some time I will start to write it up.

…………………………………

I was in the Wiener Holocaust Library in London yesterday, in fact, and have seen and made notes on some fascinating items that we will be writing about in depth soon.

The aim is to provide as definitive a list of all holdings on Kitchener as we have time to bring together while the project runs.

To start you off, you might want to take a look at the holdings at USHMM (the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum), which has a large number of photographs and some family accounts. I deeply admire the work of the USHMM – and have always found their archivists to be fantastically kind and helpful people.

I collected together a note of the USHMM holdings as a PDF a while ago, but I don’t think many have spotted it yet, so we thought we’d bring it to the front for a few days … and it’s here: Kitchener holdings USHMM

There are some great pictures, including some images of the huts and other buildings. I know many descendants want to know more about what the camp was like, and these images help to build a picture.

I do now have a plan of the camp, courtesy of the Wiener Library, and am looking into how to bring this information to you – not least because it’s quite large! We also need to finalise some copyright issues, but hope to bring it to you in some form before too much longer.

…………………………………

USHMM also have some good photographs of the refugees – on day trips to Ramsgate, for example, as well as of men in the camp itself (don’t forget to let us – and USHMM – know if you see anyone you recognise).

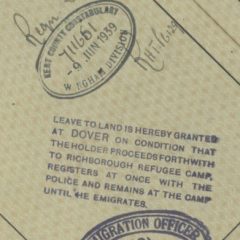

Contrary to some popular perceptions, the men were not ‘locked away’ at Kitchener. They did need a pass to go out and there was a 10pm curfew, but apart from that, they could and did go to local shops, to the cinema, to swim in the sea, for bike rides, and coastal walks. My father took trips to London, for example, and a friend of his from Germany simply absconded to work in the north of the country when he’d had enough of ‘communal living’.

The camp was crowded, and basic, and there was a lot of work to be done in creating what amounted to a small town in less than month, and then maintaining it as habitable. But when you’ve spent some time in the archives, as I have recently, and read detailed accounts from the time about what was happening in Germany and Austria, and read letters pleading for a way out from some of the many tens of thousands of Jews desperate to get away … Well, let’s just say it’s a salutary reminder that although the dormitory accommodation may not have been ideal, and the mass catering not great, Kitchener was a very far cry from what these men had escaped, and from what was still to occur across the Reich territories for years to come.

There was concern both at government levels and among the Jewish organisers that when they opened the camp a small group of mostly upper-class local fascists might cause trouble for the refugees, but by many accounts the local people of Sandwich were, on the whole, incredibly welcoming. Bear in mind, the town of Sandwich had a population of just over 3,000 at this time. Even today, when people are more used to traveling themselves, and to non-natives living among them, you’d expect some local concern at a refugee camp situated just outside a small town whose numbers would exceed that of the town itself.

Yet, local people invited these men who had lost everything into their homes and families – they asked them home for tea, in some cases, and sometimes gave them odd jobs to earn a bit of extra pocket money. (The British government had stipulated that the men were not allowed to work, to avoid friction in a country still suffering from the ’29 crash and high rates of unemployment.) While there would undoubtedly have been instances of the unpleasant anti-semitism of the time, and anti-German sentiment too, nevertheless, local people played sports and games with our fathers and grandfathers; local teachers gave them English lessons; families attended the camp theatre and concerts; and the local cafe that had once served indifferent ‘Camp’ coffee was persuaded by some of the German and Austrian refugees to make ‘proper’ coffee (see AJR extract below): the cafe soon became a hub for games of chess and Kaffee und Kuchen. Many locals and national dignitaries visited the camp, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, in October 1939.

…………………………………

The USHMM photographs also include a picture of the huge tent used for the camp synagogue, which I know will be important to many families. Around 3,000 of the refugees observed Rosh Hashanah here in 1939 – nearly a year after so many synagogues had been burned to the ground across so much of Germany.

And as the anniversary of November 1938 is upon us again this week, let us not forget what this freedom to worship represented.

…………………………………

Although many of these traumatised men would have struggled through these long days of hard work and the unimaginably dreadful uncertainty because of families stuck in Germany and Austria, Kitchener – without doubt and without question – saved many, many lives. And those who had been in Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen, and Dachau would have known that they were fortunate to be here, even on their darkest of days.

The men of Kitchener camp sent a carnival float to the Ramsgate summer festival, with ‘Our thanks to England!’ written along the side. And on another occasion, the Kitchener men made a large natural art work outside, constructed of stands of tall grass, that read simply ‘Thank you’.

From the archives of the Wiener Library for the Study of the Holocaust, London, UK

Caption: Float from Kitchener camp with dressed up men on top and banner saying ‘Our Thanks to England’ in a parade in 1939

Image WL6121

……………………………..

The Journal of the Association of Jewish Refugees, January 2010 (extract)

by Hilda Keen, a Sandwich resident

“... One day in 1939 I had got home from school, where I was learning German among other things, and mum called from the shop [Hilda’s parents owned the Golden Crust Bakery in the middle of Sandwich – CU]: ‘Hilda, you know some German, come and help me with these two chaps!’ Two young men who couldn’t speak much English wanted to know what was in some pies that were on sale. I just managed to say ‘Fleisch’ and my mother mooed like a cow! That was the first we knew about the Jewish refugees fleeing from Germany who had been given refuge in the old huts on the Ramsgate Road. At the back of the shop were four small tables with a few chairs dotted around. In the summer months one or two people would come in for a cup of tea and gradually, in twos and threes, these quiet, polite men would congregate in the back of the shop, walking up from the Ramsgate Road. They didn’t want a pot of tea: they wanted coffee. So we made them coffee – Camp Coffee it was called, from a bottle. ‘Mrs Kimber,’ said Dr Laski, when he had introduced himself, ‘You should make proper coffee - the way we do in Austria. You must buy some ground coffee and put it in a linen bag and infuse it.’ Well, nothing ventured, nothing gained, as mum would say: she would try anything to help trade. So an urn was bought, the ground coffee sewn into a cotton bag, water poured on and brought to the boil. Success! And word must have got around the Kitchener Camp because numbers increased and the tables at the back of the shop were crowded. Once or twice I trailed home from school at Dover getting home about half-past five, only to have to stand in the kitchen because the table in the living room was full of men drinking coffee and talking mostly in English but occasionally slipping in a foreign word. We got to know some of them quite well and they became friends. Franz Mandl (we called him Frank) was a medical student who had escaped over the roof of his family home in Vienna and who brought some records with him in his suitcase. It was some of the popular music of that time: ‘Wir treffen uns in Hüttledorf am Samstag an der Wien’ and an aria from Pagliacci, ‘On with the Motley’ sung in a foreign language. When he played it on our new gramophone, I thought I had never heard anything so sad in all my life. It was the first piece of classical music I had ever heard. I still have that record. ‘Turn that row off!’, said my mother hurrying through from the shop to the bakery …”

Hilda’s article goes on to talk about a Mr and Mrs Rosenberg. Mr Rosenberg had a place at Kitchener, but when his wife arrived from Germany as a refugee, lugging a heavy suitcase, she had nowhere to live. Hilda’s parents gave up their bedroom for a time to Mr and Mrs Rosenberg, so they were indeed in a fortunate position in this context, in not only being safe, but together.

For any readers who are not familiar with the Journal of the AJR, please do look it up online. It is a fantastic resource, and one that our fathers and grandfathers would have been reading when they came to Britain. And many of them who stayed in the UK, at least, would have continued to read it throughout their lives: http://www.ajr.org.uk

…………………………………

Harry Rossney (Helmut Rosettenstein), who was often interviewed about Kitchener camp, summarised his time there as follows:

"I don’t know who put me forward for the camp to this day. All I know is that they saved my life. The area had been acquired by the British Jewish community to house refugees and they had obtained permission to rebuild it. But they needed 200 tradesmen and I was a signwriter, so I was asked to come over. In fact I was number 196. When I arrived I was given overalls and rubber boots and we all worked day and night to put up huts, level roads and instal such things as showers. Each hut could take 48 refugees and in the end we provided shelter for 3,600 Jews. I came to England and I couldn’t speak a word of the language. But the people and the country were wonderful. Even when at school I had loved the idea of England as a sort of fairyland. England in German translates roughly as Angel-land and that is how I saw it. The land of angels. I tried to fit in as quickly as I could. I loved everything about it, the freedom, the laughing faces, the relaxed atmosphere – all the opposite of Germany at the time” (Kent News, 19 January 2012).

…………………………………

Before we sign off for the weekend, can I just offer a quick shout of HUGE thanks to the FED, Manchester.

The FED have been incredibly supportive of this project, adding us to their social media feed – here, for example: https://www.facebook.com/THEFEDManchester/posts/1514905591924160

I don’t have the time to work on social media as well as the website, so all the incredible ‘get the word out’ work being done on our behalf by other organisations is immensely generous. Everyone is pushed for time and resources, and we are very grateful indeed.

Do please visit the FED in return and show some Kitchener Descendant support for the brilliant work they do: https://www.thefed.org.uk

And if you ‘do’ social media – please consider finding them there and thanking them for all of us.

THE FED is the leading social care charity for the Jewish Community of North and South Manchester. We help over 1,000 people every month, from children with special needs to people with dementia.