In New York, Ann Rollett has from the start been working hard to ‘get out the word’ there about this Kitchener camp project. She has also been carrying out research into specific aspects of it, which we will be sharing over the next few months.

For now, she has sent us a more personal piece about how she first became interested in and involved with this work, which we wanted to share with you, below.

……………………………………………..

Back in the late 1970s, my boyfriend (now husband) and I visited Victor and Kitty Cohn in their new home in Leisure World, an over-55s community in Southern California. After a tour of the various clubhouses, over lunch in the restaurant by the golf course, Victor told us about coming to Berlin in 1945 with the British occupying force and finding my grandmother, mother (age 10), and uncle (age 8), who had survived the war in hiding. My grandfather had been killed just a few months earlier by the Russians when they liberated Berlin. Victor told us how he would take an army truck and fill a bag with as much food as he could find and bring it to my mother and her family. We were so touched by his story that, years later, we named our daughter, Victoria, after him.

Not long after, my boyfriend and I moved to the east coast. The next and only other time we saw Victor was at our wedding in 1983, one year before his death.

Back then, no one in my family talked much about what had happened during the war, so Victor’s openness had surprised me.

By the early 1990s, however, my mother had become more willing to talk. By this point, my grandmother was dying, and unfortunately, my mother was unable to answer many of my questions about the family that had been lost because she had been a young child, only 7 years old in 1942, when her grandparents and other relatives were deported and her family went into hiding.

My mother suggested that we interview Kitty, her only surviving first cousin. She was 17 years old when she left Germany, and would remember more. Plus, Kitty had family pictures. I audiotaped my conversation, with Kitty and my mother, the first time they discussed their family, the war, and the Holocaust. Kitty died in 2009, and my mother now has her photo albums.

I was busy in the 1990s working and raising children, so I didn’t listen to the tapes again until 2107. The audio quality is not great and I especially had difficulty in deciphering names. Kitty died in 2009, so I began researching online, trying to fill in some of the details.

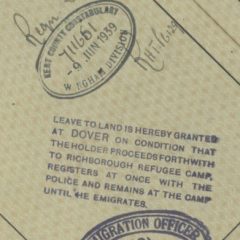

During the interview, Kitty mentioned that she and Victor came to England in 1939 because Victor was accepted by a camp, which I eventually figured out was Kitchener camp. After Victor arrived at the end of April 1939, he found Kitty a job, so she was able to get a domestic worker visa. She followed him to Sandwich about three months later.

Through my searches about Kitchener, I came across Dr Clare Weissenberg’s blog, From Number to Names. On her site, she recommended Clare Ungerson’s book on Kitchener. She also listed web resources that I have found invaluable.

As Clare Ungerson describes, when England declared war on Germany, a large proportion of Kitchener men joined the British Pioneer force –a support organization made up of foreign-born men. At the end of the war, many Kitchener men were sent back to their native countries with the occupying forces.

My mother, who was 10 in 1945, told me how much it meant to them to see Victor – to see any family member – after two and a half years in hiding. On the audiotape, I can hear her enthusiasm as she talked about Victor’s visits, remembering him as charming and handsome, like the actor Victor Mature. My grandmother became quite ill when the war ended and my mother had to take responsibility for obtaining and preparing food for the family. She remembers how much Victor did for them, visiting and bringing food frequently. She said all the British soldiers collected food.

According to Kitty, when Victor returned to Berlin, he went searching for his family and hers. Victor had left behind his parents and two younger sisters, whom he had hoped to bring to England on domestic worker visas; according to Kitty, however, they had not wanted to work as maids. Kitty had left behind her parents and two older brothers, both of whom had applied to Kitchener, but had not been accepted.

Victor found only five survivors, all from Kitty’s family – my mother, uncle, and grandmother; Hardy Kupferberg (Putti), Kitty’s first cousin from her father’s family, who had managed to hide until 1944 when she was caught and put into Ravensbrück, the women’s work camp near Berlin; and one other distant cousin, Berthold Rahfeld. According to Kitty, “Victor did not have a soul left in the world.” My mother remembers that, as the British and American soldiers came to Berlin, word got out about what they had found and they began to realize that “nobody could have survived.”

I don’t know much about the Kitchener men who returned to Europe with the occupying forces and whether any of the others found family. It must have been heartbreaking to realize that virtually everyone they loved was gone. For the few who survived, the Kitchener men and the British and American troops brought hope and help. My mother says about British and American occupying forces that “they were human.”

How much that must have meant – after the cruelty, suffering, and deprivation of the war.

……………………………………………..