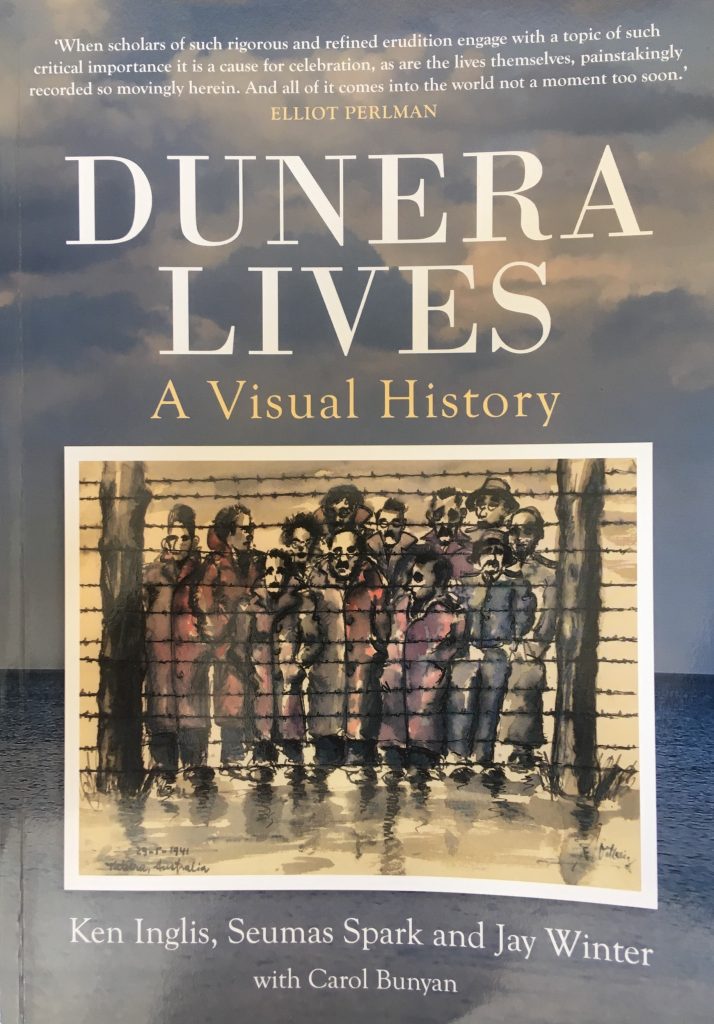

Dunera Lives: A Visual History

Ken Inglis, Seumas Spark and Jay Winter, with Carol Bunyan

Monash University Publishing, 2018

This post responds to a new book that explores the wartime experiences of the HMT Dunera deportees to Australia.

Dunera Lives: A Visual History has just been published by Monash University Publishing. A Visual History is the first of two volumes, and it explores mainly visual and creative responses to the Dunera events. We were sent a copy to review.

As ever in this context, it is difficult to obtain a definitive number for the men who were both in Kitchener and on HMT (Hired Military Transport) Dunera, given the records that are left. A co-author of Dunera Lives who has been working for a number years in the Australian archives has concluded that around 239 is a decent guide. Whatever the exact number, however, it is clear that this narrative is an important part of our shared Kitchener history.

The outline

For the most part Dunera Lives explores two main aspects of Dunera history – the notorious voyage itself, and the men’s experiences in internment camps in Australia.

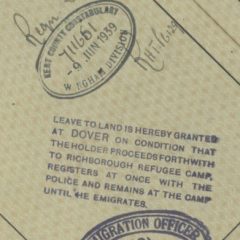

It also touches on the immediate aftermath of the war for these refugees as they settled in new countries and obtained the formal paperwork of their new citizenships. And the final section looks briefly at later life choices, outcomes, and accomplishments.

Some of the Dunera men were sent to the Hay camps, some to Tatura, some to Orange: the book explains the differences and suggests some reasons why particular men (and in some cases their families) were sent to particular camps. The Kitchener men were mostly detained in Hay camp 7. Andreas Eppstein, “a 25-year-old Jewish statistician from Breslau … and a graduate of the London School of Economics, was elected leader of camp 7. As his deputy the camp elected an older man, Dr Hans Frankenstein, a 40-year-old physician from Allenstein in East Prussia who was spokesman for a group of about 250 refugees from the Kitchener camp” (p. 128).

The book also deals to some extent with the experiences of families deported to Australia on board the Queen Mary. About three weeks after the Dunera, the Queen Mary docked at Sydney with around 265 detainees on board, having sailed from Singapore in very different conditions to those on the Dunera. On arrival, the Queen Mary detainees were taken to internment in Tatura camp 3, where they were separated into two compounds: for married couples, children, and single women, and for single men over the age of 16.

An acknowledgement

Despite a number of email exchanges on this subject with one of the authors of Dunera Lives – the thoughtful and perceptive Seumas Spark – I didn’t really know what to expect when Monash sent a copy for review. I assumed it would be a ‘text book’ of historical events.

However, the reality is quite different from the general ‘history book’ in both form and impact. The impact of the work gradually dripped its way into my consciousness – and I expect it will remain there.

My father wasn’t on the Dunera, so I do not have a direct connection to these events, and thus I had no particular expectations of the book, which will make my responses rather different to those of the many families who have been directly involved over almost 80 years, and who have made the many extraordinary contributions to this volume.

My father having been in Kitchener, however, I think I understand something of the leap of faith it must have taken for families to put their trust in someone else to respect and keep safe these personal memories and histories, formed in the most extreme of circumstances.

Before I continue then, I want to pay tribute to the families whose generous contributions form the substance of this book. Despite everything they will have experienced in being survivors, or second- and third- generation family members – with all the weight of responsibility that this entails – these people have put their trust in the editors and publishers of Dunera Lives to do justice to, and be respectful of, their families, their memories, and their histories.

Dunera Lives: A response

I read the introduction and then looked at the first few images. I was reading the captions with care, but was intending to move forwards methodically and swiftly, in the impersonal process of reviewing a book.

Having read the introduction, I planned to go through a few more pages and then return to some other work that was pending. I kept turning to ‘just one more image’, however, through into the main body of the book, and after what seemed like only a few pages in, I was still sitting at the kitchen table two hours later, and I was now examining the images with much more care.

Less than an hour after this, I went to get a magnifying glass.

My responses were changing with the images, which run through political caricature, images of violence, of desolation, of humour, and of beauty.

Some of the images are self-portraits, some are portraits of individuals on board the Dunera or in the Australian camps, some are more general scenes of camp life, and some depict the landscapes and the nature that the men found in their new homeland – even to the extent of the detailed botanical drawings made by Hans Lindau, which were created in minute form on 2,500 sheets of toilet paper, with a pen provided by the Quakers. This was an extraordinary labour of love indeed.

On board the Dunera, too, a camp constitution – much of which was put into effect on arrival – was carefully scripted on toilet paper.

I can’t begin to imagine the patience that writing this constitution must have taken.

On a rolling ship, imprisoned in the hold, with layered hammocks all around, and more layers of bodies with nowhere but the floor to sleep … In filthy, humid conditions – on something so fragile as toilet paper – these men drew up a constitution for the democratic functioning of their future lives.

Just to think on this for more than a minute is to be in awe of the certainty and the clarity of such minds – and to be deeply conscious of the men’s determination that they would not be destroyed by what had been happening for so many years in their countries of origin.

Some of the images in the book are violent, some crude, some political; some present amusing caricatures of politicians or characters in the camps; some depictions are stark, some anguished, and some have a simple beauty – it is a compelling range of response.

In Orange, 1941, by Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack, the painter presumably seeks a moment of peace, beauty, or escape: at first glance, he seems to find a memory of another life – or to seek a life that might be returned to.

The painting is a landscape with some small, red-roofed buildings caught between the foreground and the distant hills. But the landscape is not peopled – aside from the intimation that lives must be being lived in these buildings. Presumably, part of the artist’s escape is encapsulated in this moment away from other people, when confinement with others had been enforced for so long.

Centred in the image: a slashed area of deep orange rock, with sharply defined and defining black lines, rising from the soft green of the grass. It is reminiscent of many paintings of southern Italian hillsides, with flashes of bright colour picking out raised areas.

The far distance has no detail – but dark purple hills. What lies at such a distance cannot be depicted by an artist who will not have seen much beyond the wire that forms the bounds of his new abode. What lies beyond the camp confines cannot be envisioned: it cannot be given form or light or detail. ‘Beyond the camp’ is, thus, the amorphous mass of these purple hills – it is indiscernible – as it would have been to men in captivity for so long.

The picture caught my eye – like a view from a window. It is a view that would be preferable to the one the men endured day in, day out.

If this picture had been mine, I would have hung it on a wall, and pretended that it was my window – even for a moment.

There is a terrific variety of media on display here – books of poetry bound with bootlaces; pictures in crayon and watercolour; simple sketches and woodcuts and carvings. There are detailed programmes for musical and dramatic events; Christmas cards; cartoons; caricatures; photographs.

Some depictions are in black and white, while others make startling use of vivid patches of colour.

There are even sheets of music here, and a lunch menu from the Queen Mary.

There are maps; engravings on a cigarette tin; extraordinarily detailed bank notes that were in use in the camps; sports membership cards and a list for a sports team. There is even a hairdresser’s advertising sign from Hay’s camp 8, juxtaposed with exercise books for the many lessons that took place – the older men teaching both the youngsters and their own peer group.

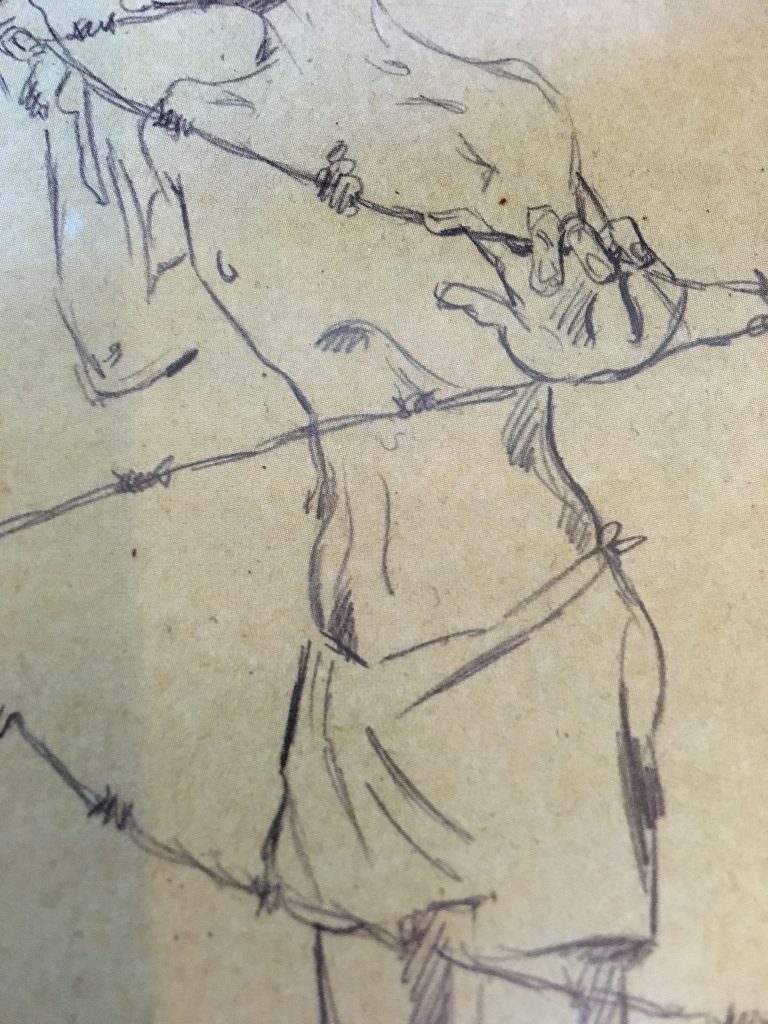

Many of the images seem to emphasise the ongoing problem of loneliness in a crowd; and many, of course, make reference to the barbed wire that surrounded them for so many long months. In image after image the wire is as ever-present as their fellow inmates; indeed, it takes on a character of its own in these varied depictions.

Barbed wire

The image of the barbed wire that surrounds the men and denies them their freedom is prevalent throughout many of the images shown in Dunera Lives.

The depictions of the wire begin on the ship: in Hans Rothe’s sketch, it divides a man’s torso piece by piece, in jagged lines that run down his body, segmenting it, as surely as he is divided from the world by the wire.

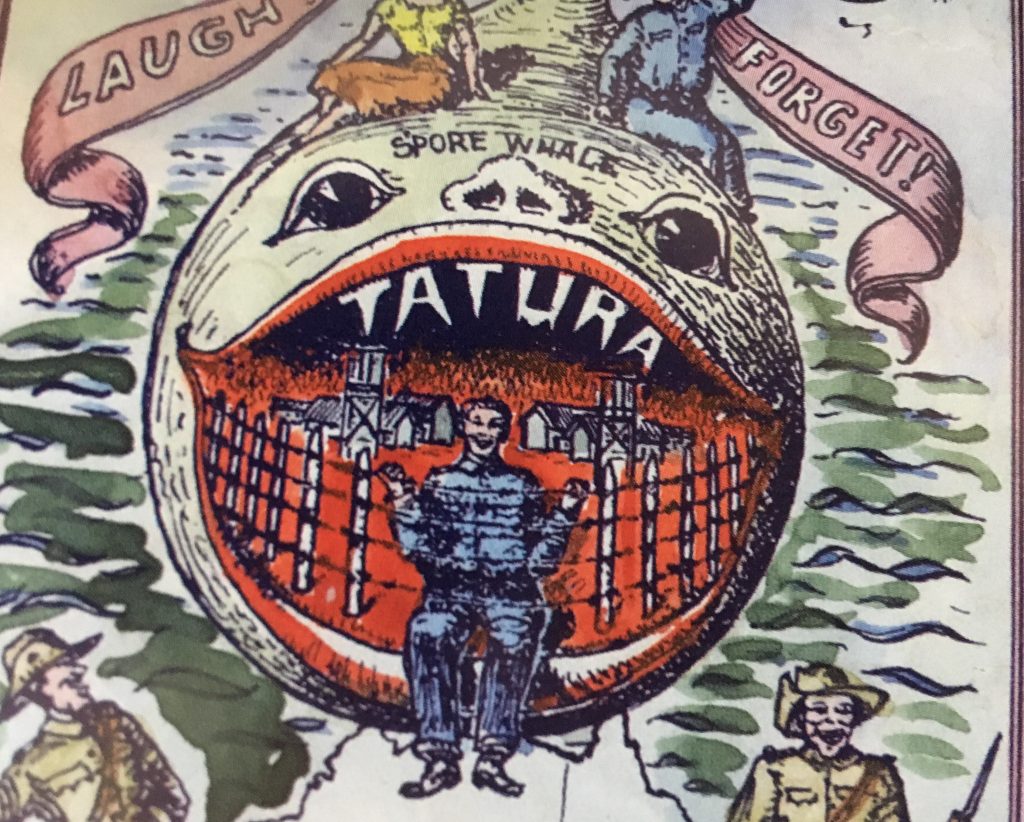

In an illustration for a programme for a variety show entitled ‘Laugh and Forget’ (a detail from which is shown below), the wire at Tatura camp forms the lower half of a whale’s teeth. The man in the mouth of the whale, Jonah-like, sits half in and half out of the enclosure. Smiling at the limits of the wire, his release will take far longer than Jonah’s three days.

The man’s head may be above the wire, but his heart and body are enclosed by it, and the layer of ‘teeth’ formed by Tatura hangs, menacingly, above his head.

When the whale’s mouth closes, ‘Tatura’ is what will crush the smiling inmate, whose apparent jollity, and that of the guards below him, belies the reality of his entrapment.

Dunera Lives is an extraordinary achievement in bringing together so many varied forms of creative response to the same basic set of circumstances. It also provides a span of official responses to what took place, and it will be a long time before some images leave me: official photographs of Dunera men with numbers on boards beneath them – depicted like criminals.

The book cannot – and has not set out to – give a detailed account of individual lives and the wider history: it couldn’t possibly achieve both this range of individual response and provide such detail. However, it certainly provides sufficient information – especially in the introduction – about the general history to enable the reader to place the images and short individual histories in a larger wartime context.

There is also a useful set of appendices, compiled by Carol Bunyan, which outline the men’s name changes, and the ships on which internees returned to Britain, as well as some interesting notes on the gradual release of the men from internment, and why they were finally able to leave the camps: to join the British army, the Australian army, or civilian employment. By early 1943, this section notes, most had been released.

Thus, Bunyan concludes, there were three main phases to do with the issue of release: from arrival in September 1940 to the arrival of Major Layton in spring 1941 – a period in which few were released; from April to December 1941, when “the most effective way out of the camp was to accept the offer of transport back to Britain to join the British army” (p. 516) – which was taken up by around 400 men; and from January 1942 onwards, when the men could join the British army, the Australian army, or the civilian workforce.

In the end, around half the Dunera internees served in one of the Allied armies, 394 went back to civilian life in Britain or Australia, and some, for various reasons, remained interned for the duration of the war.

The national archives in Australia have extensive records on HMT Dunera, and a very kind and helpful staff.

The Jewish Museum of Australia, Melbourne, has an exhibition on Dunera history (see short video below), and the Sydney Jewish Museum also holds a number of items relating to the Dunera history: https://sydneyjewishmuseum.com.au/collection/hay-money/

See also more information on the Sydney Jewish Museum holdings here:

http://www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au/exhibition/objectsthroughtime/dunera/index.html