The migration context

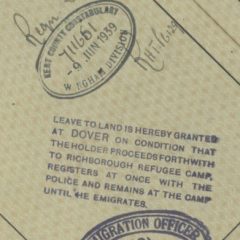

Under a suddenly increasing pressure of migration numbers following the Anschluß, in May 1938 the British Home Office introduced a visa system. Up until this point, German and Austrian passport holders had been able to enter Britain without a visa – immigration was controlled at the port of entry. With some exceptions, mainly for wealthy or ‘famous’ people, visas were only granted to those with particular skills or abilities, however: agricultural and domestic workers were in high demand, for example, and the latter led to German Jewish women from all social classes becoming servants in British homes, under the Domestic Visa system.

This being German bureaucracy of the 1930s, a vast amount of paperwork was required to leave the country, including medical certificates, many copies of passport photographs, CVs, proof of qualifications, lists of possessions to be transported (and many items were not permitted to be taken out of the country), exit permits, certificates of good conduct, as well as certificates to state that no debts were due, and that all taxes had been paid.

There were also heavy taxes levied on those leaving the country, and by 1938, each person was only allowed to take 10 marks with them.

…………………………………….

And then the events of November 1938 took place, and the need to get people out at all costs grew exponentially.

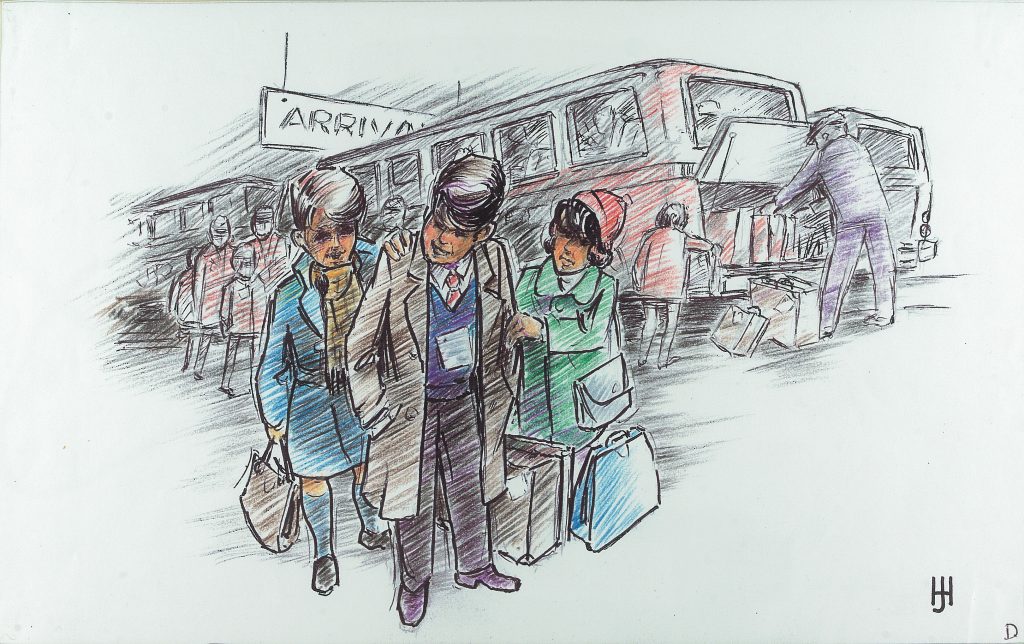

The present project was established to explore the Kitchener camp rescue of (mainly) German and Austrian Jewish men to Britain, which took place over the course of 1939, but it is important to understand that there were also two ‘sister’ rescues to Britain at this time – the Domestic Visa system mentioned above (which rescued around 15,000 women – source: CBF Minutes, 10th October 1939), and the Kindertransport. Some of the Kitchener descendant families have relatives who were in more than one – and occasionally, in all three – of these schemes.

Between December 1938 and the outbreak of war in September 1939, around ten thousand children – just under eight thousand of whom were Jewish – were brought to Britain from Greater Germany, and this scheme was known as the Kindertransport.

With the kind permission of Allen Sternstein

At its most basic, the scheme provided a simplified visa for unaccompanied children under the age of 17. Like Kitchener, it was the result of an agreement made with the British government following the events of November 1938. The Council for German Jewry guaranteed that the children would not be a burden on public funds, and that they would in due course move on elsewhere – it was largely presumed that they would go back to their families.

Whatever outpourings of national self-congratulation are sometimes heard today in this context, the Kindertransport was another transmigration scheme, and it was intended that the children would move on elsewhere once they turned eighteen. To this end, the aid organisations were also responsible for providing training so that the children would be more readily employable.

With the kind permission of Allen Sternstein

In the budget for 1939 (CBF Minutes), it was estimated that this training of the Kindertransport children alone would cost British Jewish aid organisations around £14,000. Meanwhile, the CBF continued to organise funding for many other training groups and smaller rescue schemes, including a budget of £18,000 for training a thousand Halutzim, £3,500 for the Tythrop House scheme for two hundred trainees, and another £5,000 for two hundred more trainees under the Whittingehome House scheme. The CBF was also seeking a further £10,000 for training for refugees to go to countries “other than Palestine” (CBF Minutes), and another £3,500 for the Dunraven Castle scheme for up to around another three thousand persons. In the meantime, they were also budgeting for the soon-to-be-opened Kitchener camp, for which they were setting a budget for that year of £80,000.

In terms of the aid organisations, the Kindertransport was evidence of an extraordinarily fast acceleration in response to the November 1938 events, specifically in relation to external perceptions of what was happening in Germany. Even in mid to late 1938, Jewish and other agencies in Britain had continued to prevaricate (as had the British and all other governments), deeply torn among the many needs arising after the spring Anschluß of that year, which led to insufficient funds being available for all needs: this raised “the principle as to whether the Inter-Aid Committee should continue to deal with Jewish children, in view of the fact that they at the moment had no money for such cases” (CBF Minutes, 1938). By 24 October 1938, for example, the German-Jewish Aid Committee had already spent that year’s budget of £45,000 (the equivalent of almost £3 million pounds today).

The Kindertransport numbers were initially set at what the Council felt it could fund, which was for five thousand children to be brought over to Britain (CBF Minutes, Autumn 1938); this number was later doubled. The first arrivals were to be housed in holiday camps along the coast, and they were to be transported in groups of up to five hundred.

With the kind permission of Allen Sternstein

A committee – the Movement for the Care of Children from Germany – was established and noted in the Minutes for a Council for German Jewry meeting (28 November 1938); it was also reported here that new offices were taken for the council at 69, Great Russell Street. The intention was to draw on a network of religious and other groups across the country, in order not to have to draw heavily on the Inter-Aid funds for the permanent maintenance of the child refugees. By mid December 1939, the Inter-Aid Committee had joined forces with the Movement, however, “under the joint Chairmanship of Lord Samuel and Sir Wyndham Deedes. The joint Committee would take responsibility for German children, Jewish and non-Jewish, in this country” (CBF Minutes, 12 December 1938, p.1 ).

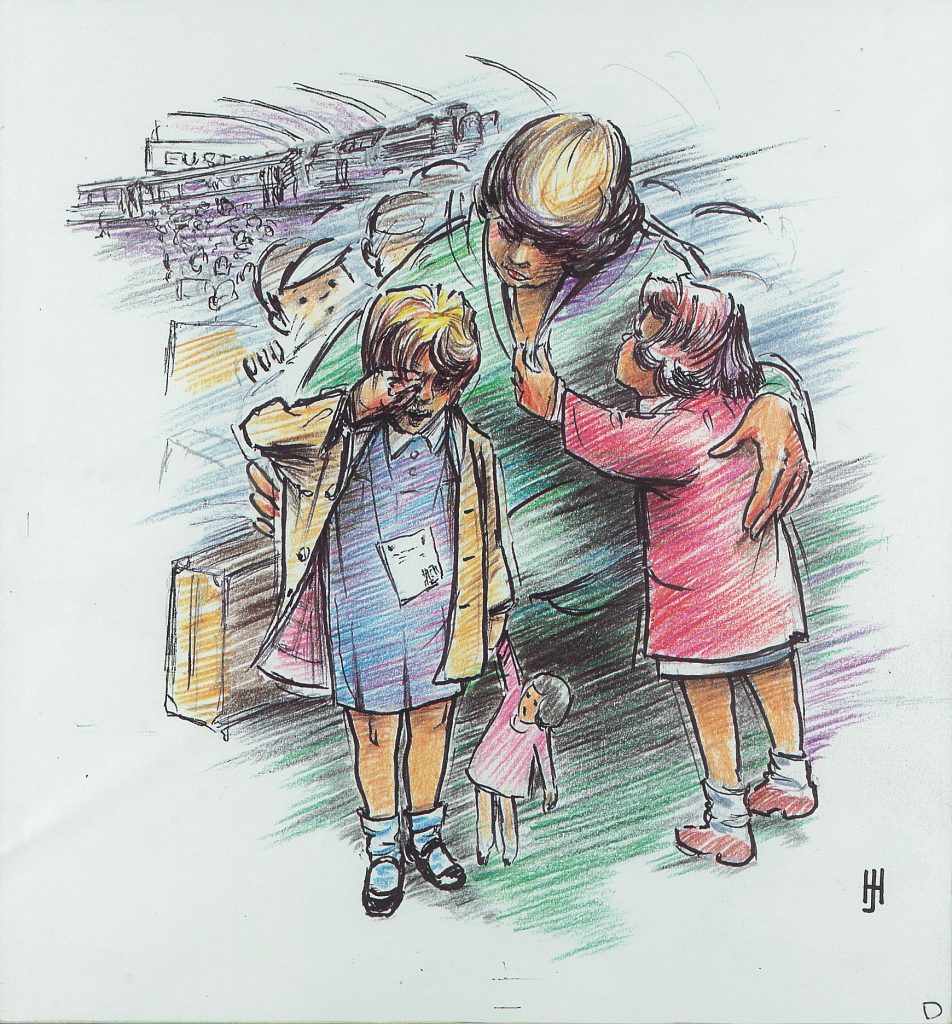

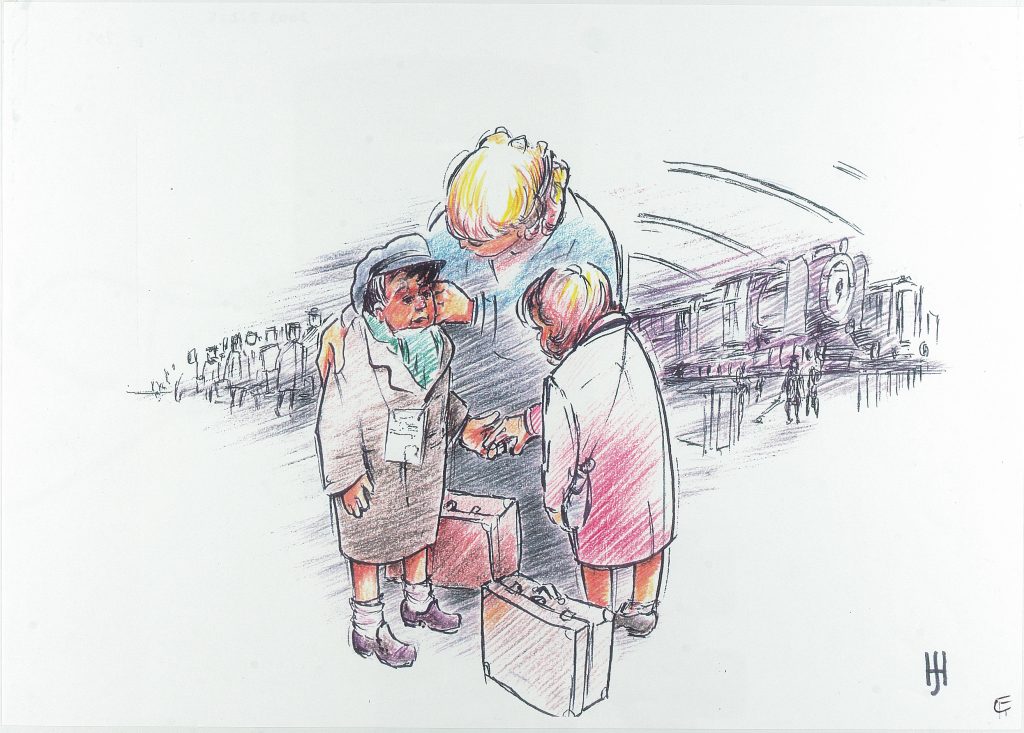

Moving from organizational to practical matters, some of the committee members were allocated the task of obtaining clothing, food, and other basic needs from manufacturers, “either as gifts or at very reduced prices” (CBF Minutes, 28 November 1938, p. 2). At this stage, it was assumed that three hundred children would be arriving from Germany “on Friday” and another two hundred a week after that. A contingent of around three hundred would also be arriving from Austria at this time. As with Kitchener, then, the whole scheme had to go from nothing to fully functioning, with considerable numbers involved, in a very short space of time.

Selections of which children would have a place on the Kindertransport were made by the aid agencies in Germany and Britain. As is often the case in such situations, those in greatest need were perhaps teenage boys, who were frequently targeted for physical assault on the streets and for detention. Families in the UK, however, preferred to house small girls. As well as such considerations, the agencies took into account psychological and social adaptability, screening from school reports, and type of background.

With the kind permission of Allen Sternstein

Many of the children were to be dispersed across the country over time, in a deliberate policy to avoid confrontation with local people; a large number went to Christian homes, and lost the ability to take part in Jewish life and customs. When compulsory schooling ended at age fourteen, a majority were to be encouraged to take up vocational training aimed at the labour market, rather than staying on and studying for higher education places. Such decisions were taken to avoid what was perceived to be the threat of jealousy and the associated potential for increased antisemitism.

With the kind permission of Allen Sternstein

One of the hostels children were placed in while hopefully awaiting homes was Dovercourt Bay Camp, near Harwich (in Essex, on the east coast of England – it must have been a very cold first winter there). Readers of Clare Ungerson’s book on the Kitchener rescue will be familiar with the name, because quite a number of the ‘Dovercourt Boys,’ as they were known, ended up at Kitchener camp.

Dovercourt, a former holiday camp, was soon filled with about a thousand children who had started their long journeys in Prague, Berlin, and Vienna. They were able to use the entertainment facilities and had some schooling, including English language classes, but boredom and missing home would have been daily problems. Sundays were probably the worst days, which is when prospective foster parents visited the camp: some children were selected while friends were left behind, and even siblings were separated by a decision made by others in a moment.

With the kind permission of Allen Sternstein

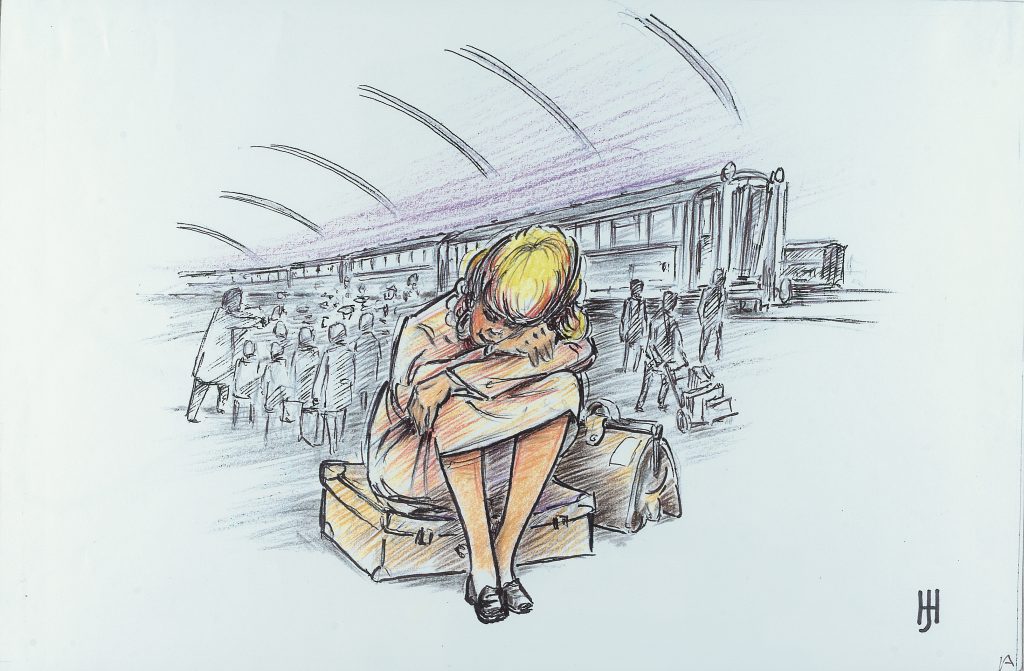

Back in ‘Greater Germany’, the distress of parents who had had to let their children go in order to save their lives is unimaginable, and many of the children themselves suffered immensely in foster homes, or in hostels when no homes could be found. Some few children were later reunited with their families, but the vast majority were never to see their parents or extended families again. Even when some family members were left alive from the Holocaust, which was rare, after six long years of war, alongside a need for fluency in the English language and assimilation into British culture and society, few can have had meaningful ties to their religion, culture, or country of origin by the end of it all.

With the kind permission of Allen Sternstein

We are so used to the idea of the Kindertransport today that it may be easy to gloss over both what it achieved and what it must have cost those involved at every level – but foremost among these costs were the emotional bonds torn apart among families, which must never be overlooked. Jewish parents must have been deeply traumatised and terrorised to conclude that the only hope for their children was with strangers in another country.

Those of us who are parents cannot begin to imagine the years-long terror that must have driven such an act made for their children’s survival: driven not by choice, or by a decision taken carefully, but by levels of urgent necessity and sheer desperation.

And while all three of these schemes – Kitchener, the Kindertransport, and the Domestic Visa – are remarkable stories of rescue, and the Kindertransport in particular is often portrayed as a symbol of hope, this was surely – and foremost – an act borne out of horror. And perhaps culturally the risk is that we all-too glibly commemorate the fact of the rescue in order not to have to look too closely at what drove it.

In broader European terms, following the events of November 1938 until summer 1939, France, Switzerland, Belgium, and Denmark permitted entry to a few thousand more Jewish children among them, and the Netherlands took in an extra two thousand.

Although the gates opened, then, they did so only slightly, and for a very short period of time.

Having said this, the French authorities, for example, instigated heavier border controls even before November 1938 was buried in the deeper months of winter – in other words, not even that horrific month passed before the gates began to close once more in Europe.

By April 1939 controls were being strengthened at the Italian-French border, and mobile units were deployed to stop people gaining access to European countries by sea.

In Luxembourg, Denmark, and the Netherlands, ‘proper’ documentation for entry specifically excluded passports stamped with the German ‘J’ for ‘Juden‘, which were deemed invalid.

And so it went on.

Border after border, and country after country closed down to Jews needing a way out so desperately.

Whatever the shortfalls, then, and whatever the limitations – the vast majority of us involved in this project today – in other words, probably a majority of those reading these words now – are alive today because of these eleventh-hour rescues to Britain.

And therein lies both gratitude – and yet, for many, an accompanying life-long sense of guilt in the knowledge that so very many women, men, and children were never given the opportunity we have had to simply live out our natural lives.

…………………………………….

Source: photograph by editor, www.kitchenercamp.co.uk

Source: photograph by editor, www.kitchenercamp.co.uk

Source: photograph by editor, www.kitchenercamp.co.uk

The Association of Jewish Refugees supported the financing of this memorial to the Kindertransport, and contributed to the commemoration ceremony. The project was initially planned by World Jewish Relief, whose predecessor, the Central British Fund, funded the scheme and found sponsors and homes for the many children saved in this rescue.

…………………………………….

Sources

CBF Minutes, 1938-1939, London Metropolitan Archives, ACC/2793.

AJR Journal, November 2003 (http://www.ajr.org.uk/index.cfm/section.journal/issue.Nov03/article=344).

Brinson and Kaczynski, 2011, Fleeing from the Führer: A postal history of refugees from the Nazis.

Caestecker and Moore, 2010, Refugees from Nazi Germany and the liberal European states.

Frank Meisler website (http://frank-meisler.com/kindertransport/).