Letters such as the one shown (translated) below will have been written in their tens of thousands among our family members who were trying to find a safe country to which they could emigrate from Nazi Germany in the 1930s.

Translation below by Helga Brown, BA Dip. Ed., née Steinhardt. Original at www.fromnumberstonames.com. Copyright Clare Weissenberg

The addresses you want, my dear son, you will find amongst the enclosed papers; one address will be sent to you by Aunt Hedel. I don’t have your cousin’s address, as sister Recha didn’t reply to my letter. I asked your cousin Recha to let you have the address of her sister by writing; she has another sister, the eldest one – Edith – there in New York. I hope she will do this. I expect you will write to her direct quite soon and thank her for her previous correspondence. You will find in one of the letters that she went in your interest from Pontius to Pilate and that came about because your father wanted to load you on a ship to Shanghai, but I didn’t want that. When I mentioned this to Dr Honegbaum – a rep. of the Aid Association – she advised me to write to London to the Chinese authorities about a visa. But I wrote to Reha in Berlin about this request and begged her to fetch the visa personally to speed up this arrangement, but Dr Honegbaum advised me to contact London because the visa there is free of charge. You will see the result from your letter. He should have said that in the first place. Too many people are waiting, as a result of this advice, in queues for hours. I also asked Myst in a letter to give you the address of Frieda’s relations, who if they didn’t want to sponsor you themselves could, perhaps, inform their friends about your predicament and ask them for advice.

…………………………………………………

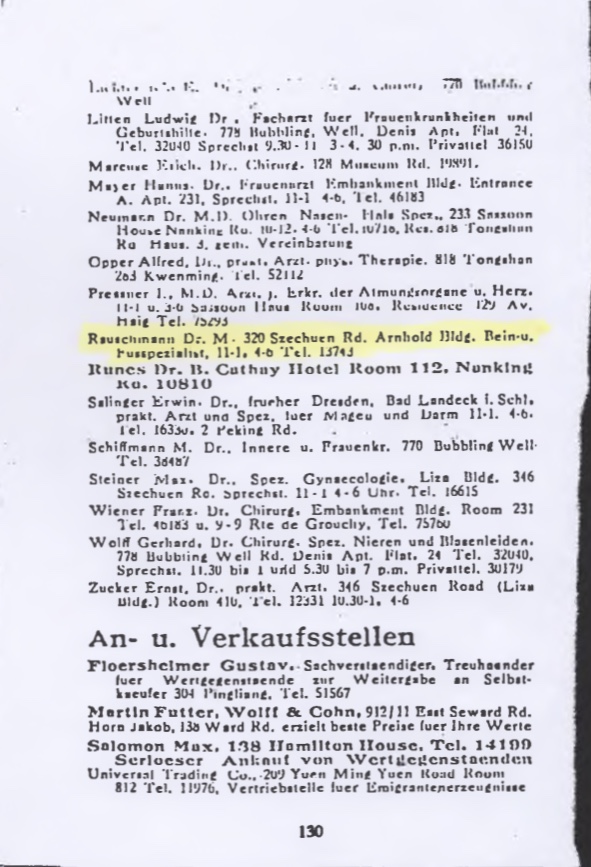

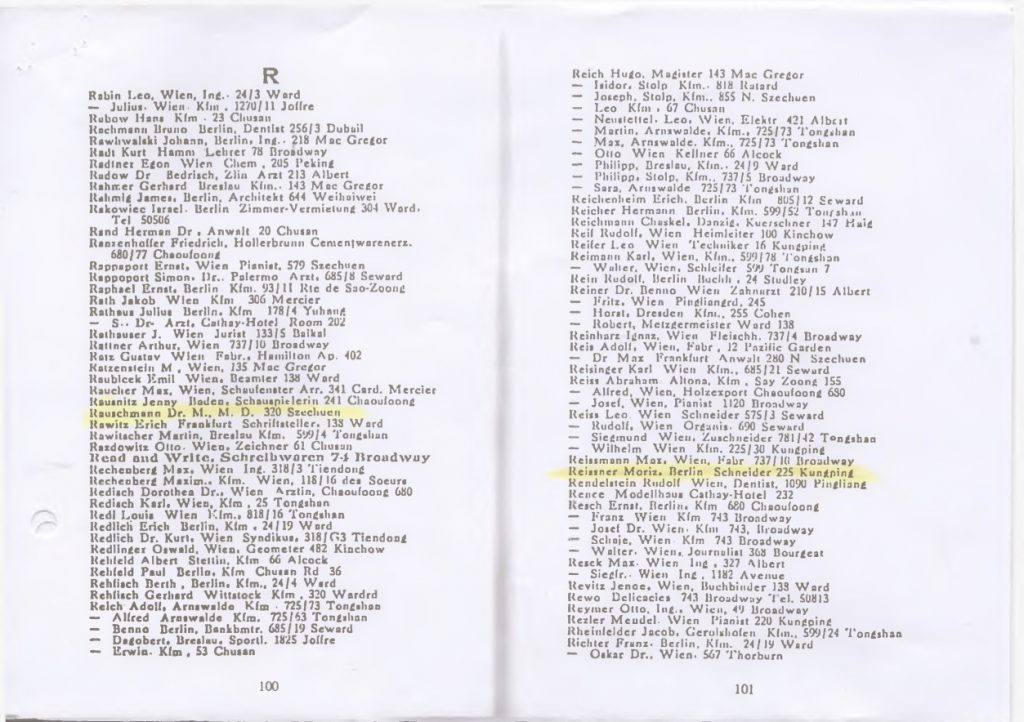

Adreßbuch

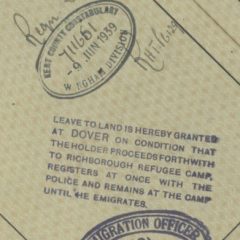

While Kitchener camp eventually provided a route out for around 4,000 Jews from Germany, Austria, and ‘the Sudetenland’ (now part of the Czech Republic), in order to more fully understand the context in which this rescue took place, we have started to look at what other options were available to people trying to escape in the late 1930s.

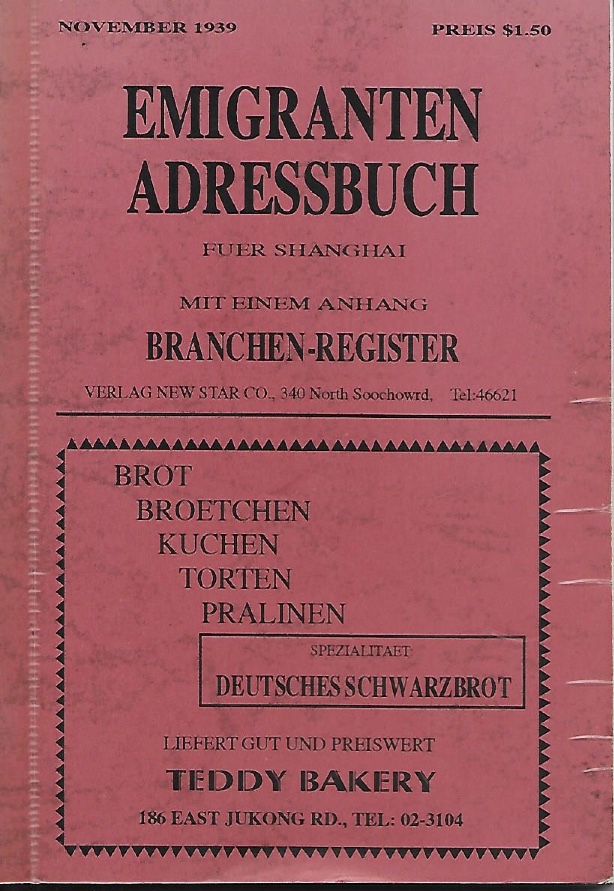

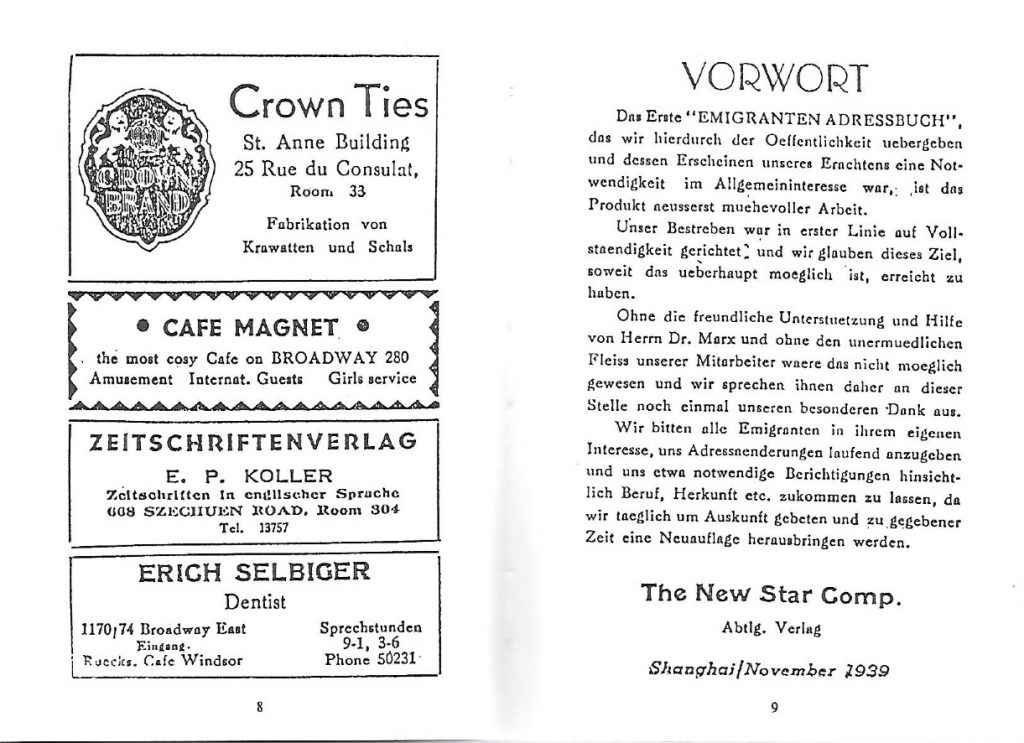

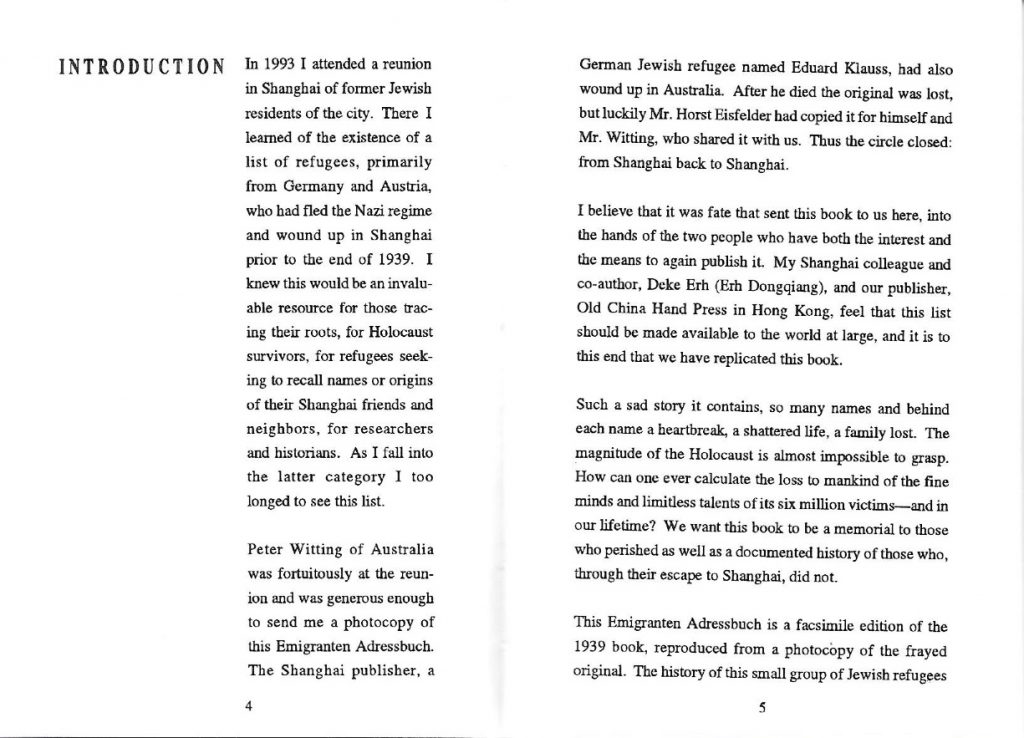

A Kitchener descendant got in touch recently to discuss the Shanghai option, in part because he has found the name of a relative in a Shanghai address book from November 1939.

For anyone interested in pre-War family history who has not yet discovered the ‘institution’ of the Adressbuch, I would strongly recommend them as a source of much useful information.

The history of Jews in Shanghai

While the favoured options for those seeking refuge tended to be Palestine, the USA, and the UK, the numbers of people being accepted by those countries were extremely limited by quotas. Many did find refuge in other areas of the world, and in particular in other parts of the British empire. However, it tends to be little known that many Jewish refugees saw out the war in Japan and China, where thousands survived the Holocaust years.

There had long been a small Jewish community in Shanghai, which had settled here for business and trade purposes during the nineteenth century. They were often referred to as Baghdadi Jews, who “made a notable contribution to the development of Shanghai as an international trading city” (Brinson and Kaczynski, p. 88). As part of an “International Settlement” area, this Jewish community was not subject to Chinese law.

In the early twentieth century the Baghdadi Jews were joined by another wave of Jewish settlers, this time fleeing first Russian pogroms and then the 1917 Russian Revolution. Many settled in the north, but others joined the Shanghai community, particularly following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931.

Max was one of Willi Reissner‘s uncles

Tragically, Max did not survive the hard conditions in the ghetto

Submitted by Vivien Harris for her father, Willi Reissner

Thus, by the time we are concerned with here, Shanghai had three synagogues, two cemeteries, a school, shops, and a hospital, for example – in other words, it was a settled and established Jewish community.

Because it was a Treaty Port, Shanghai was one of the few places in the world that did not require paperwork from immigrants to the country. However, the Japanese held the real power in Shanghai from 1937, and when they entered the World War in 1941 on the side of the Axis powers, Japanese forces finally entered the International Settlement Zone and confined the Jewish population to a ghetto.

Arrival in Shanghai

Because Shanghai did not require the same reams of paperwork as other countries, large numbers of Jewish refugees made their way here, often by boat from Trieste or Genoa; some travelled on the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Those who initially travelled to Japan – mainly to Kobe, where they were well looked after – were soon to be moved again, just prior to Pearl Harbor, when Japanese forces moved any remaining Jewish refugees from Kobe to Shanghai. Once there, they were placed with the approximately 18,000 refugees who had already moved here from 1938 onwards.

Many were housed in a refugee camp, with provisions paid for by ‘the Joint’ (the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee). Some established small businesses, including Viennese coffee houses, and the various Adreßbuch editions from these years (see example below) give the addresses, names, towns, and professions of the many thousands of Austrian and German refugees who were now living here, with their business information, where applicable.

Max and Moritz were Willi Reissner’s uncles

Submitted by Vivien Harris for her father, Willi Reissner

Before Pearl Harbor, Jewish life flourished in Shanghai, despite often poor conditions and inadequate food supplies. There were three German-language newspapers, as well as journals; there were concerts, plays, and exhibitions, decent healthcare, and good educational opportunities.

After Pearl Harbor, conditions deteriorated quickly, not least because the community was now cut off from US assistance. The original Baghdadi Jews were mostly interned, because they were British subjects, and although the refugees were not interned, at least to start with, because they were stateless, by May 1943 they were placed in a ‘Designated Area for Stateless Refugees,’ or ghetto, which extended for around one square mile. This area included a large Chinese population, and the residents were allowed to move in and out of the area by means of passes. Conditions were very poor indeed, but this was not a European Jewish ghetto: religious, cultural, and educational activities continued, although disease was rife and food extremely scarce. The German government exerted pressure on the Japanese to create a ‘Final Solution’ in this context, but this did not succeed: most of the refugees survived the war years, although around 31 were killed in a US air raid in July 1945.

According to UN Relief and Rehabilitation records, when the war in the Pacific ended in August 1945, 13,496 Jewish refugees were accounted for in Shanghai. Because local conditions remained poor, most left fairly soon afterwards. A few returned to Germany and Austria, but most headed for the USA, Australia, Canada, and Palestine.

Source: The material for this post has been drawn from Charmian Brinson and William Kaczynski, Fleeing from the Führer: A postal history of refugees from the Nazis, The History Press, 2011.

Finally, there is a Facebook page about the Shanghai Jewish refugees Museum, for anyone who is interested in, or has links to, this part of our shared history. A couple of years ago the museum was asking families to add information to their database of Shanghai Jewish refugees, so it would be worth following up on this if some of your family were here, or if you think they might have been.

And there is an interesting blog post with photographs on the subject here:

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/shanghais-jewish-quarter-hongkou

…………………………………………………

Next year, we will be carrying out research into other options that were available to Jewish refugee families during the 1930s, but for now I am signing off until January 2018.

May I take this opportunity to thank all the families who have placed their trust in this project and who have got in touch with their family materials and information. It has been humbling and an honour to be entrusted with these family stories and histories, and to help gather together these early weeks of Kitchener materials.

We are looking forward to working with many more families in the new year, when we will begin the second phase of our ‘get the word out’ campaign to reach as many Kitchener camp descendants as we can.

If over these holiday weeks you meet up with anyone who had a relative in Kitchener transit camp, please do encourage them to get in touch. They are welcome to share as much or as little information as they feel comfortable with: for some, it might just be a name and a date of birth; others may wish to share much more with the project. Both are valuable, and we are always happy to hear from anyone with a connection to Kitchener camp in Kent.

…………………………………………………

And as we gather with our families to light the candles, or to decorate the tree, we remember our fathers and our grandfathers, our uncles and our cousins – and many of us will reflect on what this extraordinary rescue has meant, perhaps especially as we engage with the children in our families today.

For those still lighting the evening candles, Chag Sameach!

And for those with Christmas approaching, Happy Christmas!

See you all in 2018.

And I hope you have a happy and prosperous new year.