Kitchener Camp 1939 Register

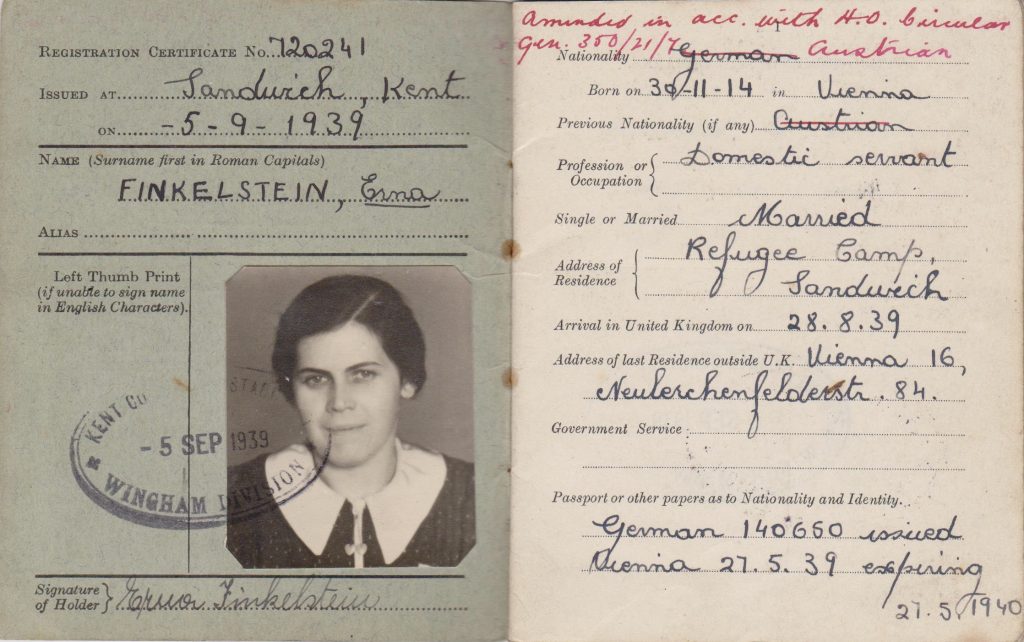

As many of you may know, around the outbreak of the Second World War, the British government took a form of national census to see who was in the country, and where.

It is known as the 1939 Register.

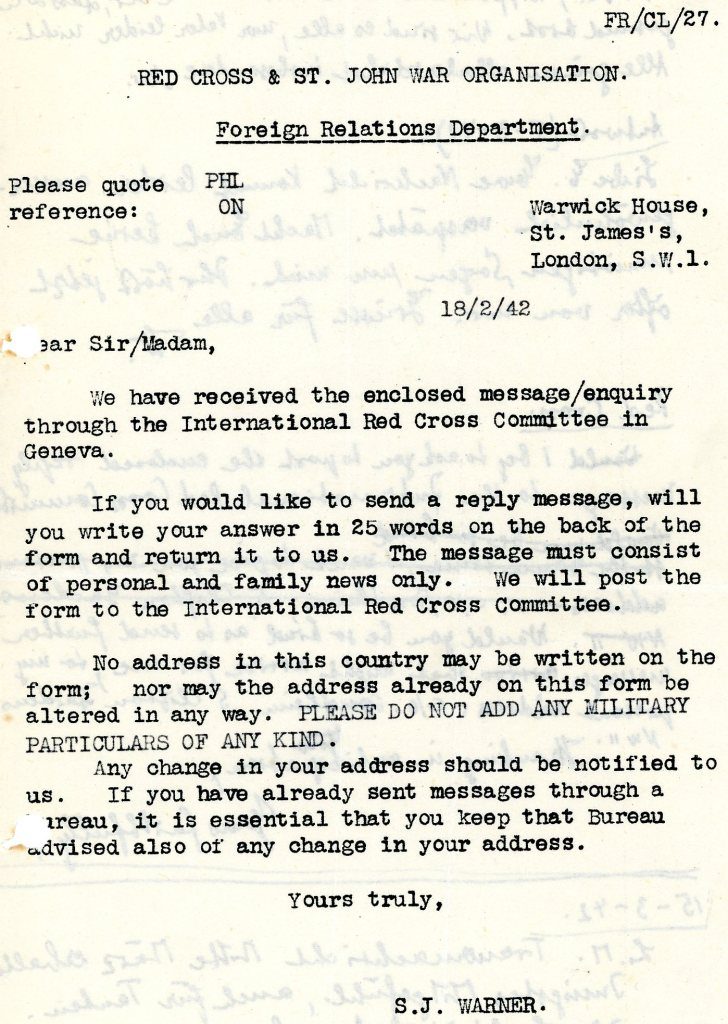

I knew nothing of this when I started the Kitchener project, but a number of descendants had been finding the Register online and sending me their extracts from it. These images from the Register can be viewed at the National Archives at Kew. For a fee, the Register images are also viewable online through Find my Past: you may look up a specific name to be taken to a single page of entries.

National Registration Day: 29th September 1939.

The Register enabled officials to issue ID cards, and the information it contained also assisted with the distribution of rations during the war.

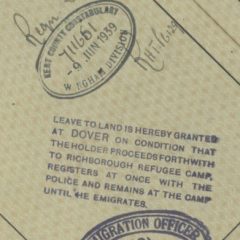

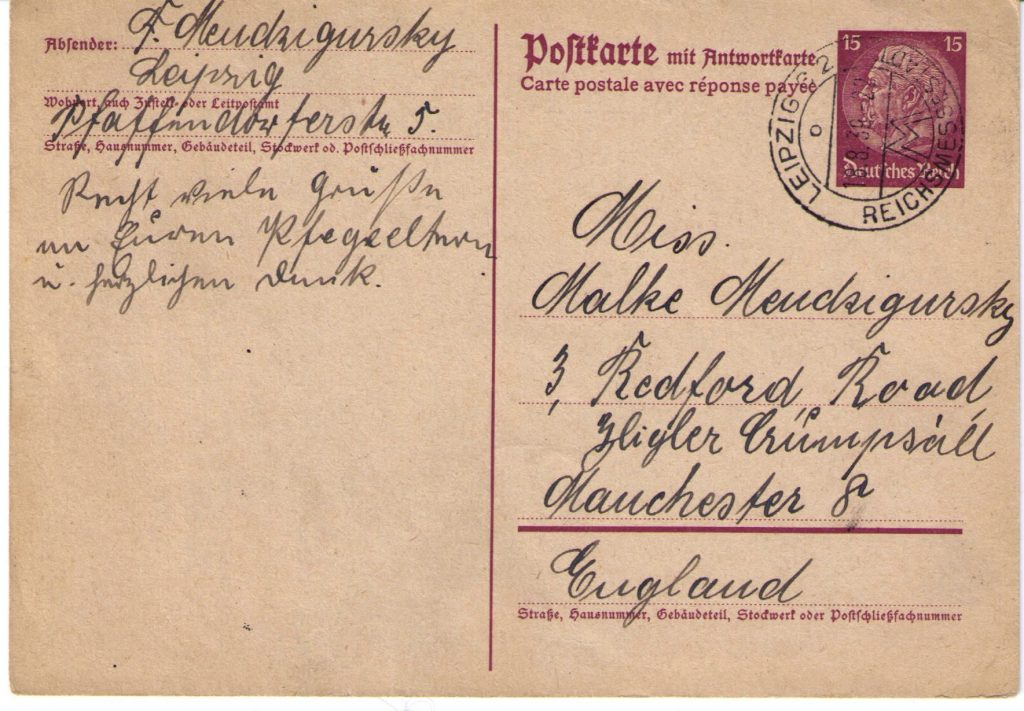

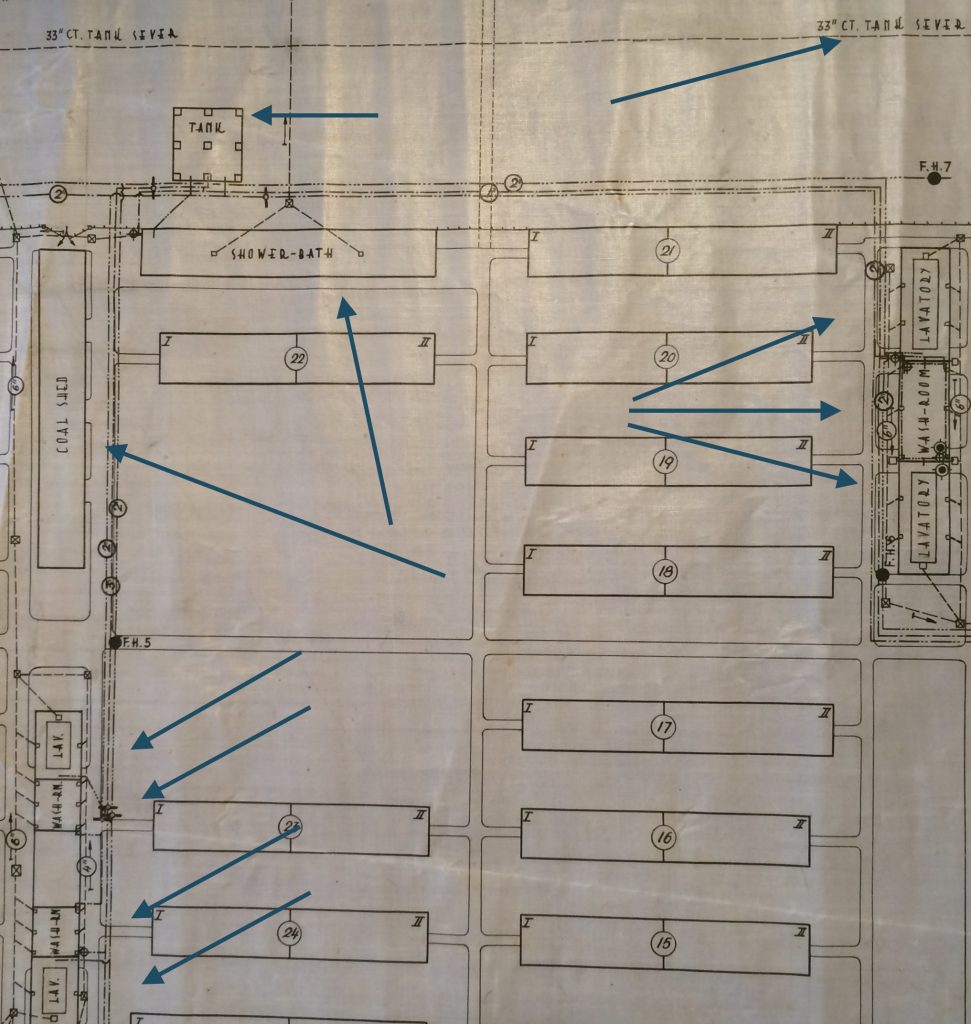

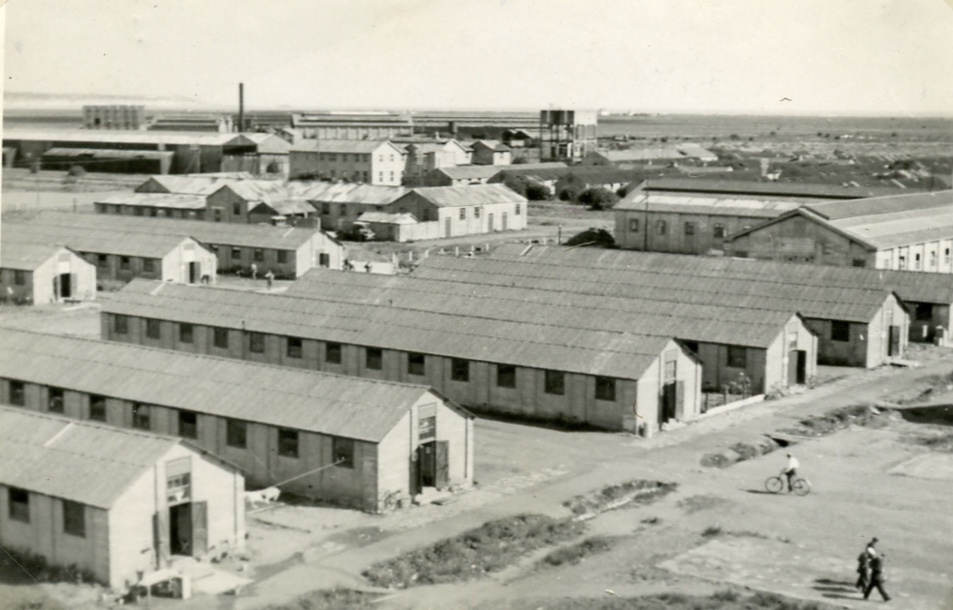

In light-hearted terms, for Kitchener camp, Richborough, Kent, we basically have ‘Householder’ Jonas May (Kitchener camp director) – and a ‘household’ that comprises around three and a half thousand mainly European, mainly Jewish, mainly men’s names.

For the purposes of the present research, then, this is an immensely useful document, and we have been given permission by the National Archives to transcribe* the Kitchener camp entry from the Register as part of this project.

*See the end of this blog post …

The previous national census had been taken in 1931, but this was subsequently destroyed in a fire during the Second World War.

The 1941 census didn’t take place because of the war.

Thus, the 1939 Register was – and remains – a crucial document both for government administration from 1939 to 1945 and, of course, for our purposes today.

It should be noted that this is not a complete list of the men and women who stayed in Kitchener camp for some period of time during 1939 and 1940.

Rather, it is a snapshot taken on a specific date.

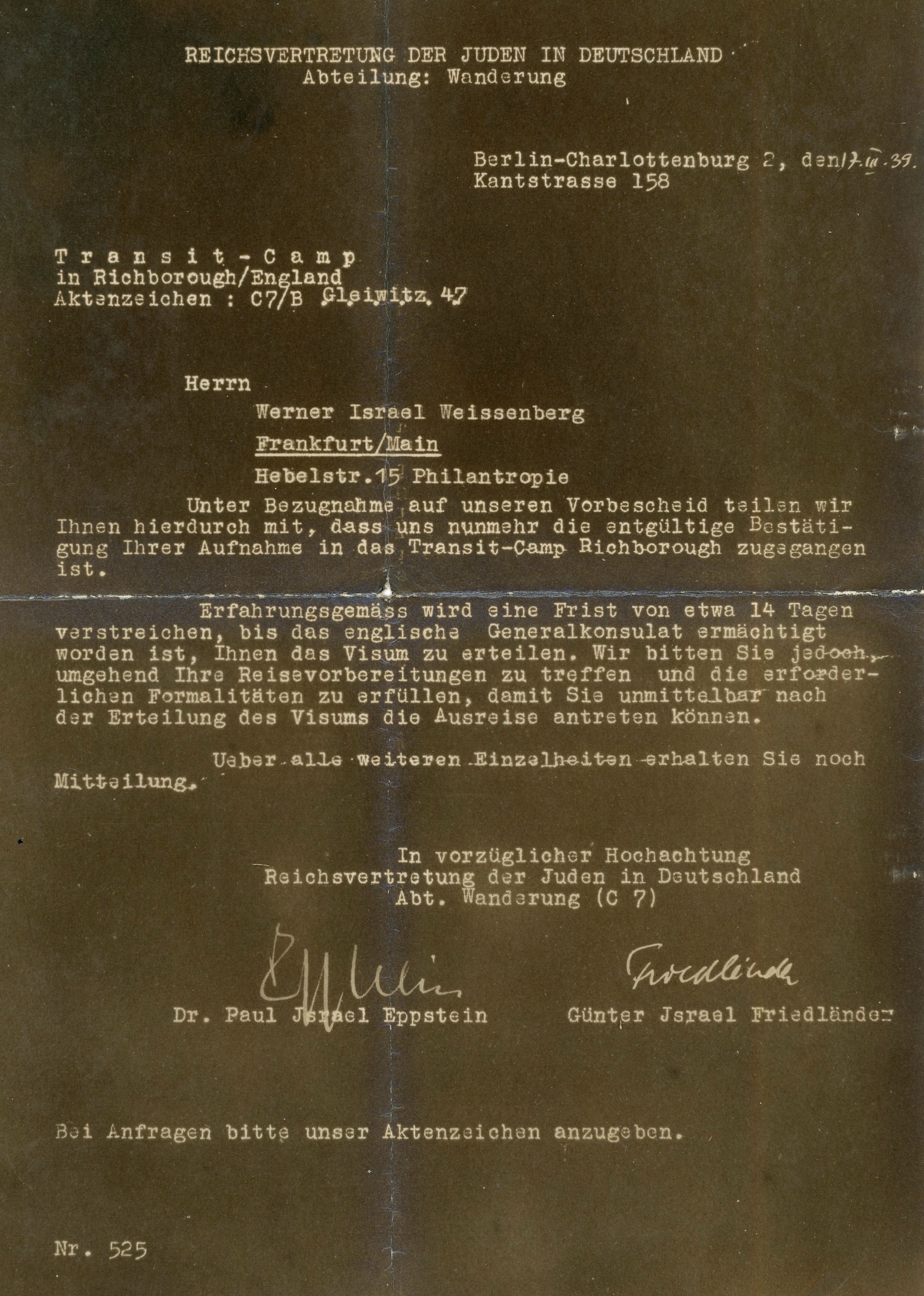

Some residents had not yet arrived, and some had already left, so if your father, grandfather, or other relative is believed to have been in Kitchener, the fact that they may not appear on this list should not be taken as proof of anything. If you have other documentation or photographs that show they were here, that documentation takes precedence over this list.

Nevertheless, the 1939 Register is a remarkable document, and – history in the making – as far as we know, this is the first time the information from the Kitchener camp entry has been made publicly viewable in its entirety.

We will be looking into various ways of displaying this information over the coming weeks and months, but I did want to get the main list uploaded as a priority in order to help us reach more Kitchener descendant families. Not everyone knows their relative was here, and this may help people with their enquiries.

At the moment, it is presented here in the form of a simple PDF that you can search using the ‘Find’ command on your desktop or laptop.

Who to thank?

The big question, of course, is who do we have to thank for all this work?

Can you imagine transcribing all this information … for three and a half thousand or so people?

Well, that was the barrel I had been staring down, until I found myself chatting away to another KC descendant recently – and I happened to mention the frustration of knowing this list was out there, but not yet having it in a form we could use: we are allowed to transcribe the information, but we are not allowed to upload images of the list itself.

In any case, if we had been allowed to upload the images, these would not have been searchable, and so it would have been of limited use.

What a lot of work lay ahead …

Now, I’ve been in business for a long time, and I can’t tell you how rare it is for someone to simply pick up a task of this scale, do it, and return it – with no fuss, a minimum of questions, and nothing asked in return.

And yet – Kitchener descendant Peter Heilbrunn has done just that.

Not only has he undertaken what must have been hours (weeks!) of transcribing, but he has provided the information in a number of easily searchable tabs on a spreadsheet, including by surname, by gender, by occupation, and so on. And as soon as I can make some time available, I will be uploading the information in these different forms.

Which only leaves me to say – from all the Kitchener descendants, historians, and the future researchers who will now pour over this information in fascination and with gratitude – Peter – I take my hat off to you and thank you on behalf of us all for what is, in effect, an extraordinary act of commemoration.

Please click on this link to view the PDF – Kitchener Camp 1939 Register

Source: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/

Peter has suggested the following additional notes:

- The Findmypast access provides both a transcript and a view of the original Register page;

- MyHeritage now offers access to the Register but only in transcript form;

- Of the approx. 3,500 people recorded on the 29th September as being at Kitchener camp, 469 cannot be viewed. They are “closed records” because the person is less than 100 years from date of birth. However, relatives who think their ancestor was at the camp can apply to have the record made public, provided that they can supply a death certificate;

- The Register has been subsequently updated and shows change of name through marriage and otherwise.