For a copy of my recent talk at Belsize synagogue to commemorate the Kitchener camp rescue in the context of the events of November 1938, please see the end of this post.

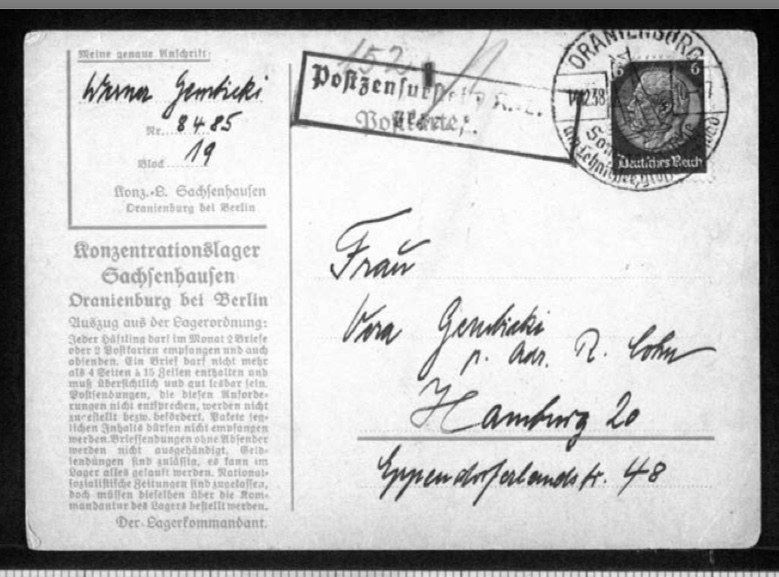

Reproduced here with the kind permission of Werner Gembicki’s family, and the Leo Baeck Institute, where the extensive Gembicki archive is located.

……………….

The Association of Jewish Refugees (AJR) commemorates the events of November 1938. "Following on from the 80th anniversary and the United Synagogue’s ‘Leave a Light On’ initiative last year, the AJR again encourages the illumination of synagogues and households on the night of the 9th November to remember the Kristallnacht." https://ajr.org.uk/latest-news/remembering-the-kristallnacht-by-keeping-a-light-on/

‘Kristallnacht’ commemoration, Belsize synagogue

November 1938

In commemoration of the dreadful events that were to be the trigger for the Kitchener camp rescue, the Association of Jewish Refugees (AJR) held a service at Belsize synagogue, London, on 7 November 2019 (http://www.synagogue.org.uk).

Belsize was founded by German Jewish refugees in 1939. It was a special place to be – especially on this date.

That November 7th is a meaningful date for my family can be understood from the copy of my speech, uploaded below. The service was led by Rabbi Wittenberg, whose grandfather would have been my father’s rabbi in Frankfurt. He was rounded up and imprisoned in Dachau, as my dad was.

I was therefore deeply honoured to be asked to say a few words at the service about these events and about the experiences of our fathers and grandfathers – especially on this particular date and in this moving context.

I was also honoured to speak in company with Eli Abt, a Kindertransport survivor from Breslau, who spoke movingly for the first time about his family’s harrowing experiences over these months and years.

And with the new Director of the Wiener Holocaust Library, Dr Toby Simpson, who read from some of the 356 direct testimonies of November 1938, which were brought out by Alfred Wiener to safety in Britain in August 1939: https://www.pogromnovember1938.co.uk/viewer/about/gathering-and-preserving-testimonies/

You will be pleased to hear that the congregation was very interested in the Kitchener history, and that I also met new ‘Kitchener descendants’ whom we hope to see at some of our events in the near future.

……………….

I’ve been asked to upload a copy of my talk, which can be found below.

……………….……………….……………….

‘Kristallnacht’ commemoration, Belsize synagogue

A talk given by Dr Clare Weissenberg, a Kitchener descendant, and Editor and Designer of the online Kitchener camp project

……………….

Thank you for inviting me to speak about Kitchener camp – at this service to commemorate ‘Kristallnacht’.

My father – Werner Weissenberg – was one of 30,000 men arrested during those few days. He was imprisoned in Dachau until February 1939.

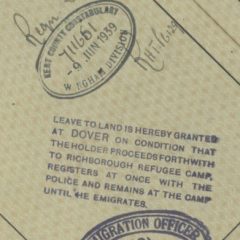

He was one of thousands desperate to escape Germany. And in June 1939, he was finally rescued to safety at Kitchener refugee camp in Kent.

……………….

What do we know about the 30,000 men imprisoned in November 1938? Who were they – these husbands, sons, and brothers … ?

Why were they selected for arrest? How many subsequently emigrated? How many were killed in the Holocaust?

……………….

While we seem to know little about the tens of thousands caught up in ‘Kristallnacht’, descendants of those rescued through Kitchener camp are interweaving the wider history of the November arrests with individual accounts of 4,000 of these men who were rescued to Britain.

Where were they from? Did they have wives, and children? What happened to their families? What organisations assisted their efforts to leave?

……………….

Kitchener refugee Lothar Nelken was a judge before his profession was forbidden to Jews, and in British wartime documents he is recorded as being ‘a weaver’. What did other Kitchener refugees do before anti-Jewish legislation changed forever so many thousands of lives, so many tens of thousands of life chances, and so many hundreds of thousands of chances at life?

Who were these men?

……………….

In the 1930s, my dad was a physicist at the University of Breslau – until he was forced out in 1936.

Drawing on his Jewish fraternity network, Werner obtained a rare teaching post in mathematics at Philanthropin – a Jewish school in Frankfurt am Main.

He supplemented his small income by teaching private English lessons, which were taken to increase his pupils’ chances of successful emigration.

And so my father was teaching children in Frankfurt when the November Terror was unleashed and four synagogues were set alight. He was arrested with thousands of others, including Rabbi Wittenberg’s grandfather – who was also imprisoned in Dachau.

Numbers vary, but it is estimated that at least two thousand died or were killed in the weeks following November 1938.

Werner wrote to a friend: “Those of us who escaped with our lives can be said to be the lucky ones.”

……………….

One condition for release from the camps was that the men had to leave Germany immediately. Until they left, they remained at risk of re-arrest.

And so the men were to emigrate first, establish jobs, somewhere to live, and then their families would join them to live in safety.

But, the declaration of war in September 1939 meant that many Kitchener refugees were never to see their families again.

The Wiener Holocaust Library has a list of over 600 Kitchener wives and children – a majority of whom did not survive the Shoah. Included among these are Lydia and Alfred – the wife and young son of refugee Hans Friedmann. Lydia secured Hans’s place at Kitchener, but tragically, despite his efforts, Hans was unable to rescue his wife and son in time. They were deported from Frankfurt to Minsk and killed in the Shoah.

……………….

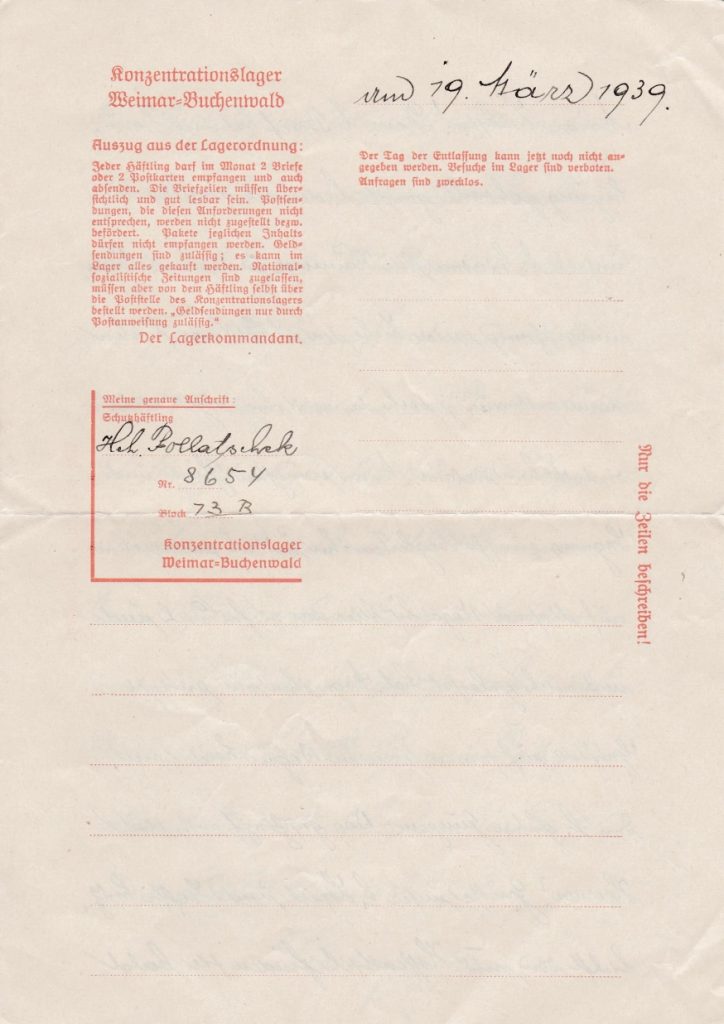

In reality, no-one wanted these would-be refugees. And so these desperate, starved, tortured men – from Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen – had nowhere to turn.

Editors note: The Evian conference, 6th July 1938 Over a period of nine days, country after country expresses sympathy for the plight of German Jews, but only the Dominican Republic agrees to accept additional refugees. There is little criticism of German anti-Jewish policy and no willingness to accept more refugees; indeed, the conference sparks further border closures (Source - F. Caestecker and B. Moore, Refugees from Nazi Germany and the Liberal European States, 2010, p. 34)

……………….

Meanwhile, in Britain …

A philanthropic group – the Central British Fund – had been organising the rescue of German Jews for some years. (Today, we know them as World Jewish Relief.)

Following the mass arrests, the CBF increased their efforts, observing that very soon, “the German government would take such steps as would lead to the practical extinction of Jews in Germany” (Minutes, Council for German Jewry, 1st December 1938).

Their Kindertransport rescue began first, and there was a ‘domestic service’ scheme to bring out thousands of women.

What is less well remembered is the Kitchener camp rescue, which began in February 1939 – which saved my father, and thousands of other German-speaking Jewish men.

……………….

Given the urgency and the great need, and the British government’s reluctance to admit more permanent residents, the CBF suggested a transmigrant refugee camp.

The aim was to bring out 3,000 men in a first tranche. All of whom had to be able to show a good chance of emigration to a third country.

As the first refugees transmigrated, another 3,000 would be brought out to safety (Minutes, Council for German Jewry).

Kitchener refugee Viktor Sonnenfeld left Kitchener for Australia, with his wife Gertrude in July 1939. En route, they learned that Gertrude’s father had been beaten to death in Vienna. However, their daughter was born in freedom in Australia in November 1939, and I recently had the great honour to meet this now-80-year old woman – who flew halfway round the world to be at the opening of our Kitchener exhibition just a few weeks ago.

……………….

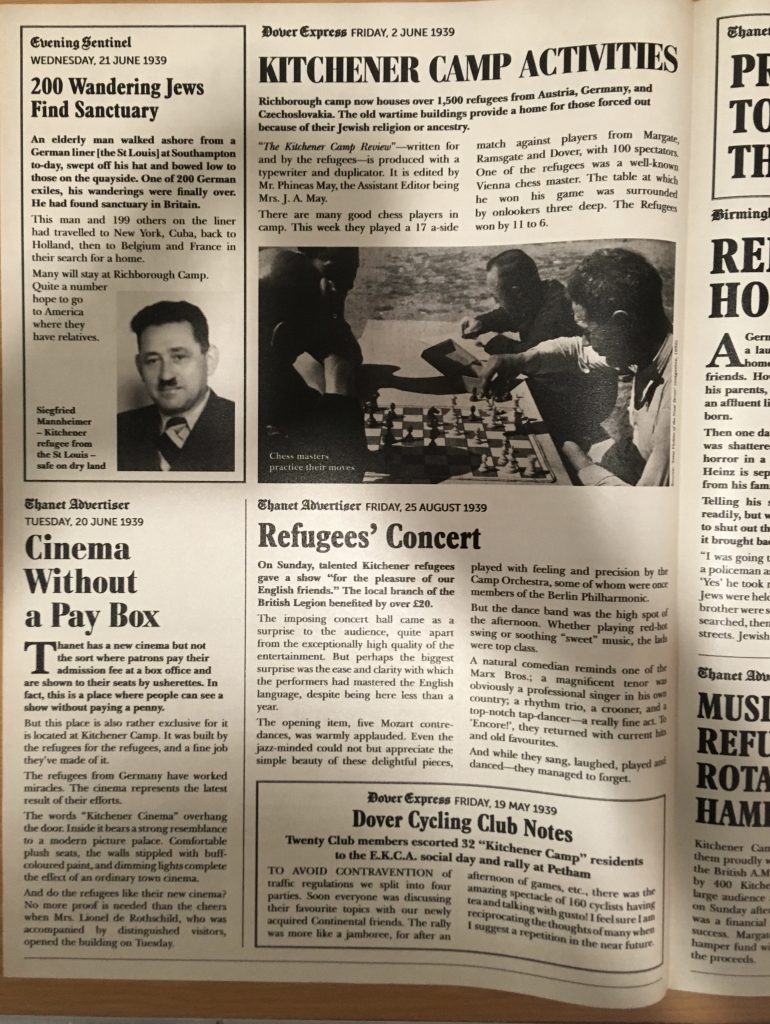

Kitchener was a long-abandoned World War I army training base, near Sandwich, on the Kent coast. The refugees’ first task was to make it habitable.

An extraordinary undertaking – to construct a small town for thousands in a little over a month. The chief carpenter, refugee Walter Brill, said they were willing to work all hours, because “for every hut we finished, we knew another 72 lives could be saved.”

The refugees worked hard, restoring around 50 residential huts. Over time they built a post office, in which refugee Otto Neufeld worked. Otto’s young daughter Lili survived the war in hiding, with a French family. Afterwards, they were reunited, but found communication difficult because Lili now only spoke French, while Otto spoke German and English.

Kitchener camp had a store, recreation rooms, and two dining halls – including kosher provision for those who wanted it – such as Kitchener refugee Josef Frank, who through all the intervening years kept his Kosher dining slip and Orthodox ‘work shift’ ticket.

There was a barbers, a dentist, and a hospital. Two rabbis served religious needs – one of whom was Dr Werner van der Zyl – student of Leo Baeck.

There was a concert hall – with classical music played by refugees such as Franz Schanzer – a cellist. He transmigrated to New York in April 1940. There were musicians from the Philharmonic orchestras of Vienna and Berlin, as well as jazz, and popular music-hall tunes. Hundreds of local people came to social events at Kitchener camp.

Others took part in sports matches, or games of chess; they took the refugees on days out to Dover, Canterbury, and local beaches. The people of Sandwich brought our refugees into their homes, such as Werner Gembicki and Herbert Mosheim, who were befriended by Maude Peabody and her family. Some remained friends for the rest of their lives.

Some of the refugees remembered Kitchener as little more than a labour camp; others recalled it as a place of refuge and safe haven. How it was regarded by thousands will have differed according to life experience, character, age, and class; whether families were safe or not, and what happened subsequently.

Kitchener was not an internment camp: those came later, in summer 1940. Kitchener was watched over by the refugees themselves, such as Ignatz Salamon, from Poland, or Wolfgang Priester from Berlin – both of whom were day guards.

The camp was run by two British Jewish brothers – Jonas and Phineas May, who gave many months of their lives to what must have been a traumatic and demanding task.

Phineas May’s diaries of these months are housed with the Wiener Holocaust Library. Other diaries and materials on the Kitchener website describe: the journeys to Britain, the refugee experience in the camp; weddings, births, and deaths. They describe the enlistment of 887 Kitchener refugees in the British Army, or later internment – in Britain, Canada, or in Australia. Diaries and letters discuss the emigration to America of over 600 Kitchener men – some as late as summer 1940.

……………….

Every week brings new Kitchener descendants to our group, with family photographs, letters, and documents.

I always encourage families to add a photograph – because a face humanises the history – from ‘thousands of men’ towards the personal and the individual, which seems especially important in this context.

Many families say – ‘My father never spoke about this time’ – ‘We knew we couldn’t ask’.

Years of silence: of not being able to ‘ask’. Years of absence: of a hole where understanding should have been. Decades of guilt, because Kitchener children didn’t know ‘enough’. …

Today, when Kitchener families are in a room together, what is noticeable is the noise. It’s like someone took a cork out of a bottle as everyone starts to talk and to exchange their histories! We sometimes sign off our emails – in recognition of our shared history – “From one ‘Kitchener Kid’ to another.”

……………….

The Kitchener Descendant Group is a life-affirming and meaningful practice – which brings among us a better understanding of our recent history: it brings people and families together.

An American descendant wrote to me recently – her sister was a young child when her parents left Britain in summer 1947, after her father was rescued at Kitchener in 1939.

She wrote, “This is such a wonderful moment for me. May G-d bless the rescue you are memorializing – for all the men who passed through the camp. My father is now shown as a brave survivor and no longer just a number in the Dachau log book.”

……………….

In closing, Rabbi Wittenberg – I want to acknowledge your grandfather, who was rabbi at Frankfurt in November 1938, when Kitchener refugees were being arrested off the streets and from their homes – having broken no laws, and having done nothing wrong.

In our fathers’ darkest days, your grandfather provided comfort and spiritual sustenance – especially in Dachau, where hundreds died, and where all were brutalised and starved from the day they arrived.

To know your grandfather was in that dark place where our fathers were, lifts the burden. And means a lot.

Thank you – all – for bearing witness to this often forgotten chapter in German Jewish refugee history. And for listening to the story of the rescue of my father – especially on this date – November 7th, which was his birthday.

……………….

With sincere thanks to Professor Clare Ungerson for her work to bring this history to light in Four Thousand Lives: The Rescue of German Jewish Men to Britain, 1939 (History Press)